Designing Peer-To-Peer Command and Control

In this post we will discuss the design and implementation of peer-to-peer command and control protocols in general, as well as the concrete example of the peer-to-peer design implemented in Covenant, an open-source command and control framework, as of v0.2 (released today), which I will refer to often.

Command and Control

To start at a high level, Command and Control (C2) refers to the process of establishing and maintaining control of implants on a single or on a set of targeted victim machines. A C2 framework typically provides the ability to communicate with implants via a communication protocol, issue commands to the victim systems, and receive the output of these commands back on the C2 server, to which an attacker generally has physical or direct virtual access.

P2P Command and Control

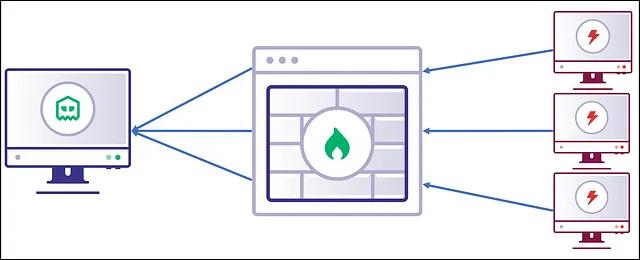

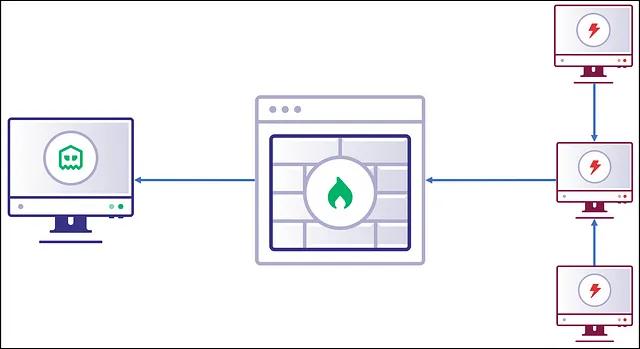

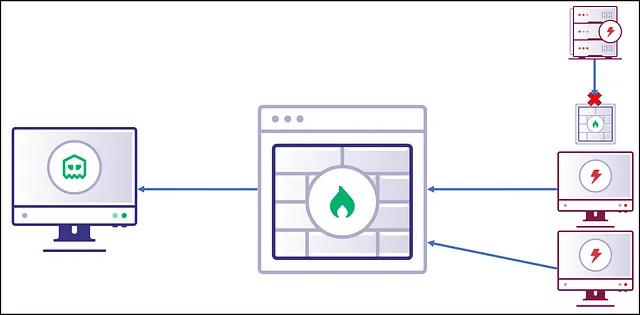

Command and Control (C2) protocols rely upon a synchronous or asynchronous communication channel between each controlled implant and the C2 server. Peer-To-Peer (p2p) C2 protocols allow for a single implant to maintain the communication channel back to the C2 server, while all other implants communicate over a “mesh” network that funnels communication through the single egress implant.

Advantages

There are many advantages to this approach. One, is that the reduced egress communication channels provides less potential indicators to defenders that may be attempting to identify the malicious traffic. Defenders tend to prioritize traffic inspection on the edge of the organization’s network over internal traffic. With a sufficiently large set of implants, an increased amount of egress communication channels may tip off a defender to your activity.

Another advantage to this approach is that of access. Well-protected networks may treat certain classes of traffic differently internally than they do at the edge of the network. A common example of this is an organization that allows HTTP traffic outbound over the edge of their network to allow employees to browse the internet but may restrict HTTP traffic originating from servers or other high-value network subnets. This type of restriction may prevent common C2 frameworks that rely on each implant to establish an egress communication channel from maintaining access to these restricted servers or high-value network subnets.

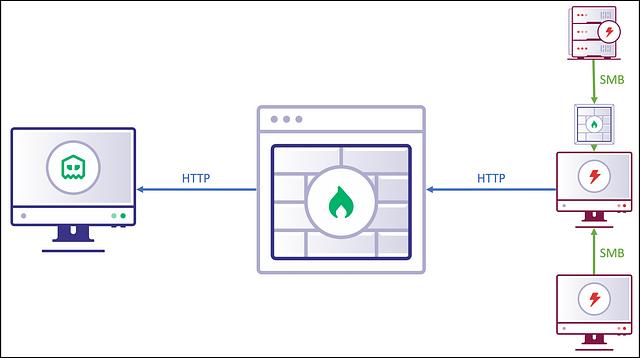

A C2 framework can utilize a different type of communication channel for egress traffic than for the mesh network to solve this problem.

We often can’t be sure of the protocols that will assure our success before landing the first implant on the target network and putting the protocols to the test. Unfortunately, this is often too late to implement new protocols into a C2 framework, unless we have a significant amount of time and resources. As C2 framework developers, the best we can do is to implement as many protocols as we can in preparation and/or make educated guesses ahead of time at the types of protocols that will allow us to succeed.

Selecting Protocols

At SpecterOps, we often find that many of the same protocols will provide success on the majority of the networks we find ourselves assessing. There are certainly exceptions to this rule, but we can be reasonably certain that a set of protocols have legitimate business use that require them to be allowed. For instance, it is a reasonable assertion that HTTP will be allowed outbound over the edge of the network if an organization expects employees to be able to browse the internet. This is one of several reasons that HTTP is a common egress communication protocol for C2 frameworks. However, as mentioned earlier, it is common that HTTP is not permitted from high-value areas of the network.

For the secondary, internal communication protocol, we must rely on the technology of the victim system for both ends of the communication channel, which influences our decision on what protocol to select. Ideally, we’d like a protocol that blends in with the normal traffic of the network and is simple to implement in our implant.

At SpecterOps, we often find that organizations largely rely on a Windows stack for business operations, and a very common protocol required internally for Windows systems is SMB. Named pipes are a native Windows technology that allows for inter-process communication across remote systems over the SMB access protocol and is fairly simple to implement into a Windows implant.

For these reasons, Covenant utilizes HTTP as the egress protocol and SMB named pipes for the mesh protocol, which is a common set of protocols for this type of behavior.

However, there are many different protocols that could be used for peer-to-peer protocol. For a successful peer-to-peer protocol, we just need a means to read and write data between two systems. There are many inter-process communication options on a primarily Windows network, including WMI, mailslots, Active Directory, or even just raw TCP or UDP sockets. For now, however, we will stick to the SMB protocol via named pipes.

Extending the Graph

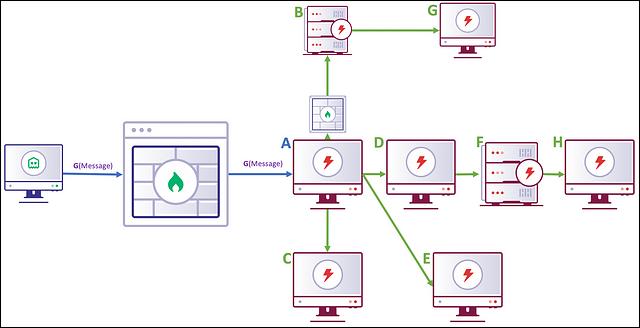

Now that we have defined the protocols we will be using, we’d like to expand the p2p mesh, or graph, beyond a single “hop”. Since we have a protocol that is capable of connecting compromised endpoints, we can extend this behavior to a full p2p mesh that hops between several nested, compromised endpoints.

These connected endpoints form a directed acyclic graph (DAG) of compromised endpoints. With the added complexity of these communication channels, implants now must track connected “child” edges as well as have the knowledge of which edge eventually leads to the C2 server. Once again, attackers must think in graphs.

You could also, theoretically, create a directed, cyclic graph for your C2. Meaning that implant messages could route back to a node it has already traveled through (i.e. A->B->G->A). I can’t think of many reasons why anyone would want to do so, and it would increase the complexity of the implant, so I mostly ignore this option and refer to the graph as a DAG for the remainder of the post.

Implementation

There may be multiple ways to accomplish these objectives, so many of these implementation details will be specific to Covenant, but I would guess that many of the methods are utilized in many different frameworks. In Covenant, each implant (or “Grunt”) is only responsible for knowing where each immediate edge leads and which edge eventually leads to the C2 server. A Grunt is not responsible for knowing the entire path to the server or the entire path to a nested child Grunt.

The graph structure is maintained by Covenant itself, and it must use this graph to craft messages that all intermediate Grunts will be able to interpret which direction to send the message next along the path within the graph. Covenant messages sent across the wire to the egress Grunt are obfuscated and stuffed into HTTP messages, but eventually these messages translate into a GruntEncryptedMessage JSON structure that looks something like this:

{

"GUID" : "3630b87066",

"Type" : 1,

"Meta" : "",

"IV" : "srwjK0WYY/XvFBPXGD7MOg==",

"EncryptedMessage" : "bU86lKwVJn1sb5m7U1Kekr3qg2KjKyNZeOP1rVoshjGpVK5LURcfYN6sWWGs+20NJUfhz7Jj6o7geAymVwJknRV2s4+Y8uDnRndGxZZKCjiiBGVWMVCPWewRzA93U+SLM55hqdmuLWLR2SPjxGzR5A==",

"HMAC" : "n+whkeAvDV+RcLPvazmkakrX8oPwBCCSqRQ8Pte9Ayo="

}

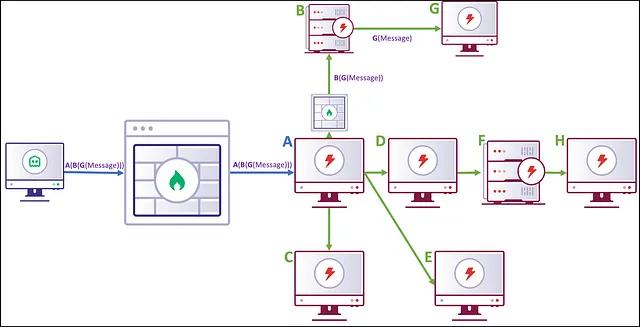

A Grunt receives this structure and somehow needs to determine which direction to send the message. As an example, let’s label all of our Grunts with simpler names and walk through the process step-by-step:

The C2 server delivers a GruntEncryptedMessage, referred to in the diagram as G(message), to the A egress Grunt that has been crafted to be delivered to the G connected grunt. The GruntEncryptedMessage may look like this:

{

"GUID" : "G",

"Type" : 1,

"Meta" : "",

"IV" : "srwjK0WYY/XvFBPXGD7MOg==",

"EncryptedMessage" : "bU86lKwVJn1sb5m7U1Kekr3qg2KjKyNZeOP1rVoshjGpVK5LURcfYN6sWWGs+20NJUfhz7Jj6o7geAymVwJknRV2s4+Y8uDnRndGxZZKCjiiBGVWMVCPWewRzA93U+SLM55hqdmuLWLR2SPjxGzR5A==",

"HMAC" : "n+whkeAvDV+RcLPvazmkakrX8oPwBCCSqRQ8Pte9Ayo="

}

The A Grunt has no knowledge of the key needed to decrypt this message and no knowledge of how to route this message to Grunt G. What could be the solution to this problem?

Path Method

One option could be to include the entire path as a new field within the GruntEncryptedMessage structure, like the following:

{

"GUID" : "G",

"Path" : ["A", "B", "G"]

"Type" : 1,

"Meta" : "",

"IV" : "srwjK0WYY/XvFBPXGD7MOg==",

"EncryptedMessage" : "bU86lKwVJn1sb5m7U1Kekr3qg2KjKyNZeOP1rVoshjGpVK5LURcfYN6sWWGs+20NJUfhz7Jj6o7geAymVwJknRV2s4+Y8uDnRndGxZZKCjiiBGVWMVCPWewRzA93U+SLM55hqdmuLWLR2SPjxGzR5A==",

"HMAC" : "n+whkeAvDV+RcLPvazmkakrX8oPwBCCSqRQ8Pte9Ayo="

}

Grunt A would inspect this message, would see that Grunt B is the next Grunt along the path, and has knowledge of how to route to Grunt B, given that it is connected with an immediate edge in the Graph. Grunt B would perform a similar operation and pass the message along to Grunt G, which is able to decrypt and interpret the message from the server.

Limitations

However, this method suffers from a couple of unfortunate properties. First, this violates our premise that a Grunt should only know about Grunts that are connected through immediate edges. By viewing a single message, a Grunt gains knowledge of an entire path through the graph. Similarly, defenders that are able to intercept or otherwise obtain access to this GruntEncryptedMessage gain intimate knowledge of the p2p graph and may be able to discover large parts of your implant mesh that is unrelated to the message you are actually trying to deliver. Even worse, this portion of the message is unencrypted. All of the hard-earned cryptographic properties we obtain through the use of an encrypted key exchange protocol are wasted on this plaintext path, making it easier for defenders to identify your activity throughout the network. While these Grunt labels might not directly correlate to an internal hostname, it still gives a defender unnecessary information about the extent of your operation.

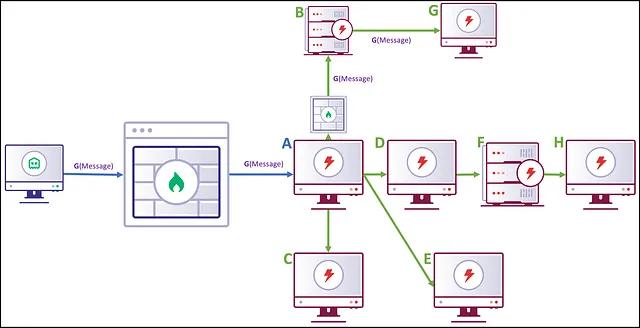

Recursive Method

Covenant avoids this problem by using a recursive GruntEncryptedMessage structure. Instead of placing the entire path as a plaintext field within the message, the path is recursively encrypted. For instance, we take the final message that we would like to deliver to Grunt G:

{

"GUID" : "G",

"Type" : 1,

"Meta" : "",

"IV" : "srwjK0WYY/XvFBPXGD7MOg==",

"EncryptedMessage" : "bU86lKwVJn1sb5m7U1Kekr3qg2KjKyNZeOP1rVoshjGpVK5LURcfYN6sWWGs+20NJUfhz7Jj6o7geAymVwJknRV2s4+Y8uDnRndGxZZKCjiiBGVWMVCPWewRzA93U+SLM55hqdmuLWLR2SPjxGzR5A==",

"HMAC" : "n+whkeAvDV+RcLPvazmkakrX8oPwBCCSqRQ8Pte9Ayo="

}

We treat this entire JSON structure as a message and encrypt this using the symmetric key for Grunt B, and stuff the resulting value into the EncryptedMessage field of a message crafted for Grunt B:

{

"GUID" : "B",

"Type" : 0,

"Meta" : "",

"IV" : "jKbU80WYY/XvFBPwVJnPWd==",

"EncryptedMessage" : "kr3qg2KjKbU86lKwVJn1sb5m7U1Kekr3qg2KjKyNZeOP1rVoshjGpVK5LURcfYN6sWWGs+20NJUfhz7Jj6o7geAymVwJknRV2s4+Y8uDnRnd6lKwVJnGxZZKCjiiBGVWMVC6lKwVJnPWewRzA93U+SLm7U1Kekr3M55hqdmuLWL20NJUfhz7=",

"HMAC" : "KwVJnPAvDV+RcLPva93U+krX8oPwBCCSqRQ8PtLPvaz="

}

And we do this once more, by taking this entire JSON structure, encrypting this using the symmetric key for Grunt A, and stuffing the resulting value into the EncryptedMessage field of a message crafted for Grunt A:

{

"GUID" : "A",

"Type" : 0,

"Meta" : "",

"IV" : "geAymV0WYY/XvFBqg2KjKyNZ==",

"EncryptedMessage" : "6lKwVJn1sb5m7U1Kekr3qg2KjKyNZeOP1rVoshAymVwJknRV2sjGpVK5LURcKbU86lKwVJn1sb5m7U1Kekr3qg2KjKyNZeOP1rVoshjGpVK5LURcfYN6sWWGs+20NJUfhz7Jj6o7geAymVwJknRV2s4+Y8uDnRnd6lKwVJnGxZZKCjiiBGVWMVCb5m7U1Kekr36lKwVJnPWewRzA93U+SLm7U1Kekrb5m7U1Kekr3=",

"HMAC" : "Rnd6lKwVJV+RcLPva93U+krX8oPwBCCSqkr3qg2KjKy="

}

With this method, a Grunt decrypts the EncryptedMessage field within the GruntEncryptedMessage and checks the GUID field of the decrypted structure to determine which Grunt to route the message through next. Importantly, the Type field is set to 0 for the “Routing” messages and set to 1 for “Delivery” messages. This switch indicates to the Grunt whether the message is intended for it or if the message should continue to be routed along the path.

This recursive method eliminates the previous issue of revealing the entire path to a man-in-the-middle observer. We utilize our existing per-Grunt symmetric keys, negotiated through an encrypted key exchange, to cryptographically seal the path to observers and Grunts alike. The cost is that the final GruntEncryptedMessage will be larger in size, due to the recursive encryption operations. (Note: Grunts should also not be labeled sequentially as shown in this example, as this could also leak the extent to which the network has been compromised. Fortunately, this is just an example and Covenant does not use this behavior in practice.)

Named Pipes for C2

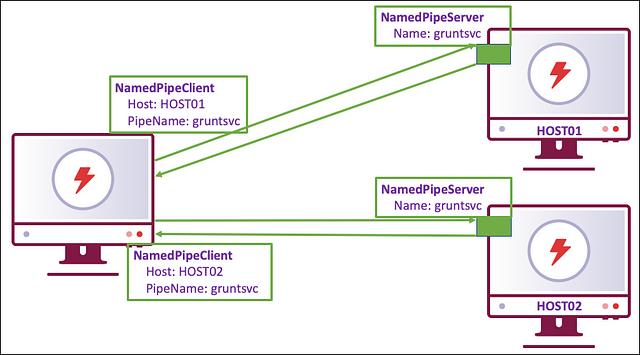

So far, we’ve covered the routing implementation in detail, but not the implementation details of the access protocol itself. While often referred to as “SMB named pipes”, what we really are doing is accessing named pipes remotely over the SMB access protocol. A named pipe connection consists of a NamedPipeServer and a NamedPipeClient. In .NET, these can be accessed using NamedPipeServerStream and NamedPipeClientStream objects.

Every peer Grunt (i.e. all Grunts aside from the egress Grunt) will have a single NamedPipeServer, and a NamedPipeClient for each immediately connected child Grunt. A NamedPipeServer listens on a pipe name, waiting for connecting clients. A NamedPipeClient connects to a server given the hostname and pipe name, which creates the named pipe. Each end of the named pipe has the ability to read and write from the opposite end.

This is sometimes referred to as a “bind” connection, meaning that the NamedPipeServer is started on the child Grunt and the parent Grunt creates the connection with a NamedPipeClient. It is also possible to create a “reverse” connection, meaning that the NamedPipeServer is started on the parent Grunt and the child Grunt creates the connection with a NamedPipeClient.

Either way, the outcome is that we have a named pipe connection with the ability to read and write from either end. However, Covenant currently implements only “bind” named pipe connections.

When opening a new named pipe, you have a few options to consider:

- PipeName — Both ends of the pipe must agree on a pipe name. By default, Grunt uses

gruntsvcas the pipe name, not exactly inconspicuous. It is highly recommended to customize this name, and Covenant even allows you to use a custom pipe name perNamedPipeServer. - Direction (

In,Out,InOut) – Named pipe streams can be read-only, write-only, or read-write. For p2p communication, we are always going to need to use read-write orInOut. - TransmissionMode (

ByteorMessage) – Named pipes can communicate as a stream of bytes or as serialized “messages”. Either could work here, but for a number of reasons Covenant usesBytemode and must serialize messages on its own. The reading end of the pipe reads bytes as a continuous stream and must have a means of determining once it has reached the end of a message. There are two popular approaches to this sort of problem: a delimiting character (i.e. a null terminated string) or prepending the length of the message and reading bytes up to this length. Covenant chooses the latter approach, to avoid limiting the character set available in messages. - SecurityDescriptor — Named pipes are securable objects, meaning that they are protected by one or more security descriptors. We could apply security descriptors that only allow the current users on

HOST01andHOST02access to the pipe but implants often need to perform some atypical credential management. Token manipulation, for instance, could render our named pipe inaccessible to the new user and orphan a section of our graph. For this reason, Covenant applies a single security descriptor that allowsFullControlto theEveryonegroup, to ensure we don’t inadvertently make the pipe inaccessible.

An important note when using named pipes within Covenant, is that two Grunt implants cannot share the same pipe name on the same host. However, a new Grunt implant can be started on the same host with a different pipe name.

Detection

Detection of general peer-to-peer malicious traffic and malicious named pipes can be difficult, but not impossible. Generally, it will be easier to detect malicious behaviors of the implant itself rather than the peer-to-peer protocol.

However, there are indicators that could be detected. Many of these detections require baselining certain metrics and comparing new behaviors to this baseline to give additional insight into the abnormality of the event occurring.

Host Detections

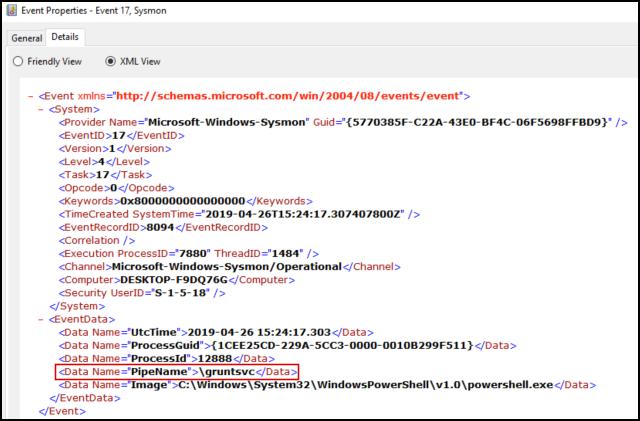

- Known Malicious Named Pipe Names — This detection is the most obvious, low-hanging fruit. C2 frameworks may utilize default named pipe names that could be detected. For instance, Covenant uses

gruntsvcas the default pipe name and Cobalt Strike usesmsagentas the default pipe name. These pipe names can be easily changed within both frameworks, but it’s still useful to take advantage of this low-hanging fruit to detect attackers that do not change the defaults.

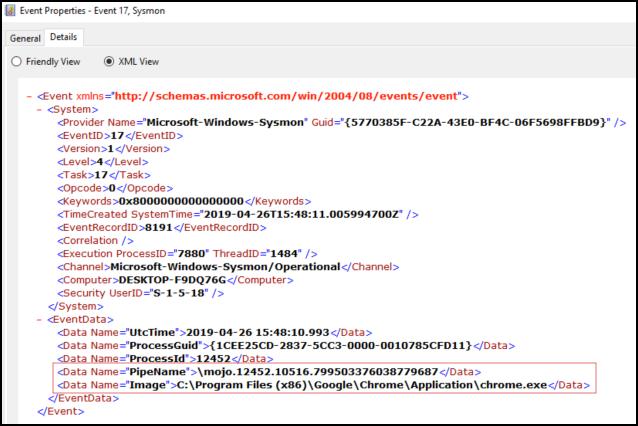

Sysmon can be used to collect information about named pipes. Sysmon Event ID 17 is generated when a named pipe is created. The PipeName field can be inspected against a list of known malicious pipe names.

- Abnormal Process to Named Pipe Relationships — To properly utilize this detection, an organization should have a way of collecting and baselining process to named pipe relationships. Sysmon Event ID 17, again, has all the needed information for this detection. These events should be collected over a period of time, and new events can be compared to his baseline.

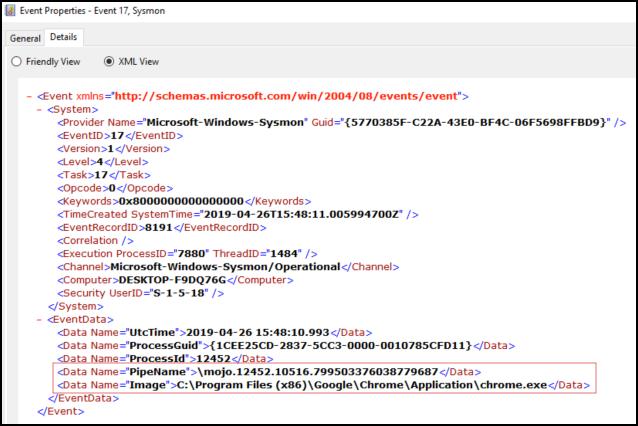

For instance, Chrome has a common set of named pipes that it communicates with that are typically of the form mojo.#####.#####.################## where # is a number. For instance:

If the process of baselining process to named pipe relationships reveals that C:\Program Files (x86)\Google\Chrome\Application\chrome.exe never, or hardly ever, creates named pipes that are not of this mojo.####.#####.#################### form, then a new event that shows C:\Program Files (x86)\Google\Chrome\Application\chrome.exe creating a new named pipe that does not match this form, say pipe123, is anomalous:

An anomalous named pipe such as this one may be worth investigating. Ideally, this detection works in conjunction with other host indicators to add additional context to a potential compromise.

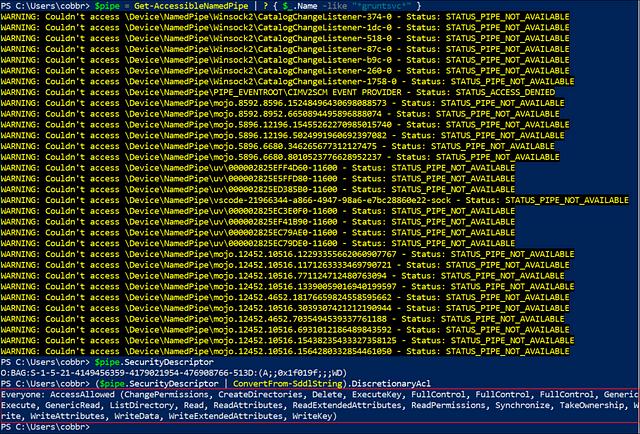

- Abnormal Named Pipe SecurityDescriptor — As mentioned earlier in this post, Covenant applies a single security descriptor to it’s named pipe that allows

FullControlto theEveryonegroup. This is not strictly necessary, but improves operator usability by quite a bit. For instance, operations such as token manipulation on a parent Grunt could change the user interacting with the named pipe and prevent the named pipe from being used if the security descriptor was limited to a particular user. For instance, we can see that a Grunt named pipe applies this security descriptor by using James Forshaw’s excellent NtObjectManager project:

An organization can take advantage of this usability tradeoff to identify potentially malicious named pipes by searching for this security descriptor. Used by itself, this detection may result in false positives. Ideally, this would be used as a complimentary indicator to increase the severity of other related indicators.

Network Detections

Network based detections that identify peer-to-peer traffic often must rely on data that is captured on the internal network of the affected organization. In many organizations this data is not collected at all, but organizations should, at the very least, collect internal network traffic at some key points within the internal network. Where specifically this collection takes place and how much should be collected will always be highly specific to the individual organization.

Network traffic patterns can often be inferred from host-based indicators. For example, Windows Event ID 4624 logon events from one system to another imply a network connection from the first system to the second. The downside of data collected from the host is that it is more prone to manipulation by an attacker on the compromised endpoint.

Some of the detections mentioned below may rely on data collected explicitly from the network (i.e. “netflow” data), while some may infer network activity based on host indicators, and some may be collected through either means.

- Remote Connections to Named Pipes — The peer-to-peer command and control graph depends upon remotely accessed named pipes. We can collect and baseline named pipes being accessed from remote systems. There could be two approaches to collecting this data. One approach is the purely network approach, using some sort of network tap or collector, SMB network traffic can be inspected to look for a named pipe being accessed. As an example, we can see a named pipe being accessed using Wireshark:

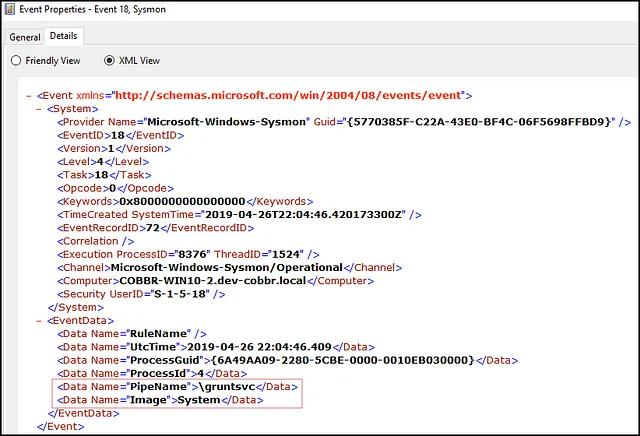

The second approach is the host-based approach. We could use Sysmon Event ID 18, which logs new connections to named pipes, and identify connections that do not originate from the current host. It turns out that when a pipe is being remotely accessed the Image field is set to System. Unfortunately, we do not get the originating hostname, but we can at least identify that the pipe was accessed remotely:

- Abnormal Host-To-Host Traffic — This final detection is more general than detecting named pipes specifically. We can attempt to identify peer-to-peer traffic in general by baselining normal internal host-to-host traffic. After a process of baselining this activity, it may be the case that certain high-value servers never, or hardly ever, create network connections with certain network subnets that mostly contain user workstations. If, suddenly, a substantial amount of network connections is identified from one of these high-value servers to a workstation subnet, this could be identified as anomalous and worthy of further investigation. This detection, again, relies upon proper baselining and may result in false positives. Ideally, this detection would be used as a complimentary indicator to increase the severity of other related indicators.

Conclusion

Peer-to-peer communication between implants is useful for command and control and is nearly essential for robust platforms. Using named pipes over the SMB protocol is a useful, common mechanism for peer-to-peer communication and is the mechanism implemented in Covenant. However, many different protocols exist that could allow for this communication, and you may see some of these other protocols eventually added to Covenant.

Detection of these behaviors can be difficult but are not impossible. It’s often easier to detect behavior of the implant itself, rather than behaviors of the peer-to-peer protocols themselves, but useful data can be collected, especially data related to the creation and use of named pipes through the use of Sysmon and/or NtObjectManager.

Peer-to-peer has officially been added to Covenant in v0.2, released today. Feel free to make use of it! The video below shows the basic how-to for using peer-to-peer within Covenant: