Apollo and Mythic: A Myth Worth Retelling

Introduction

Earlier this week, I released a new Windows agent for Mythic — Apollo. Apollo is a .NET Framework agent designed to leverage the wealth of features Mythic provides to developers in order to create an enriched operating and training experience. Apollo supports nearly all the basic capabilities an operator might need, including:

- Built-in Lateral Movement

- UAC Bypass Techniques

- SOCKSv5 Proxy Tunneling

- Third-Party Assembly and Script Execution

- Peer-to-Peer (coming soon)

In this deep-dive, I’ll detail more verbosely the features in which Apollo and Mythic implement to make operational workflow, tracking, and user experience more interactive and informative than other command-and-control solutions have provided in the past.

Due to the number of unique workflows and views we interface with, this article will be broken down based on the following table of contents.

Table of Contents:

- Browser Scripts

- File and Process Triage

- User Exploitation

- .NET and PowerShell Script Workflow

- Credential Management and Token Manipulation

- Payload and Artifact Tracking

Browser Scripts

Mythic empowers an agent developer to send data of arbitrary type as a response to an individual tasking. In its most basic form, this data could be a string of output (such as in the case of commands like “shell”). In those taskings that may want to return more complex data, we can send back full JSON blobs as a response. By default, Mythic will not perform any post processing on these task responses and display the JSON blob to the user.

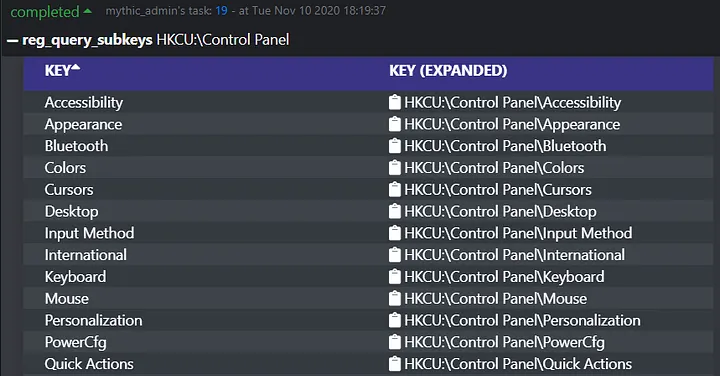

This is where browser scripts interface come into play. Each command can have an associated “browser script” specified in their definition that is responsible for rendering the output of that command. This allows a developer to extend rendered output beyond just basic text — it allows them to create a rich and textured experience for an operator. Let’s take a simple example like querying registry subkeys, which can be done in Apollo via the “reg_query_subkeys” command and whose output is shown below:

Querying subkeys is a straightforward process: a key path goes in, and subkeys are returned. Being able to manipulate output directly though allows developers to introduce new quality of life changes, such as the creation of tables as shown above. We can sort each column of the table (sorted by ascending “Key” values in the image above) and directly copy that key’s full path to our clipboard for use in subsequent commands by clicking the clipboard icon. Let’s take it one step further and query the values of one of these subkeys via the “reg_query_values” command.

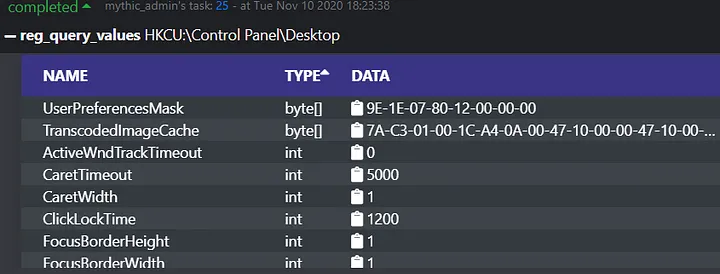

By providing more rich data types on the output of this “reg_query_values” command, we can make interpreting the data in the registry for an operator easier than ever. Values stored have associated types, those types can be sorted, and the data stored within can be copied out for later post processing.

Several commands in Apollo leverage these browser scripts throughout. While we won’t cover every command in this article, understanding how this data can be manipulated and customized is critical to understanding how other features and UI elements have been implemented.

File and Process Triage

One of the most common questions students ask us during our training offerings is “what are you looking for when you land on a machine, and how do you retrieve that information?” Our go to answer almost always is to first look for anomalous files and processes on the target, which then begs the question, “how do you know what’s anomalous?” No technology is a replacement for experience, but through enriched file data, process data, and browser scripting, we can empower students and operators alike to discover these outliers.

File Triage

Let’s first define the problem set in triaging files on disk that Mythic and Apollo attempt to resolve:

- Operators don’t have an easy way to sort and filter results based on their attributes.

- Operators want to enumerate the permissions of a file to find avenues for exploitation.

- Operators commonly list the same files and folders, and often prefer a traditional GUI interface.

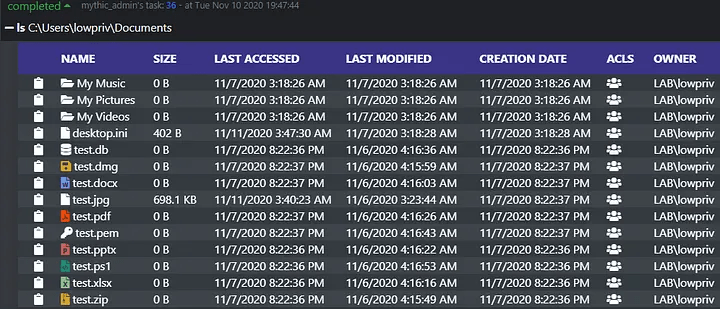

The first problem in this problem set is easily solvable by browser scripting, which we covered previously. Let’s take a look at what happens when you issue an “ls” command in Apollo.

After the response of the “ls” command is received, the associated browser script for this command is executed to format the data in the same table format we’ve seen previously. In the left-hand column we’ll see the familiar clipboard icon, which will copy the full path of the file or folder. This feature is particularly useful when issuing taskings that require reading or manipulating the file in some way. As with other tables, each of these columns is sortable. Therefore, if we wanted to find what files were last accessed or modified we can do that quickly and easily. Additionally, on the left-hand side, we can see icons for files and folders based on the type of object returned. If the file is a folder, a folder icon appears, but otherwise the icon is determined based on the extension of the file returned. Currently, the browser script can determine archive file formats, office documents, code files, SSH keys, and more. This allows an operator to easily identify potentially interesting files at a quick glance.

The column second from the right is entitled ACLs, with several group icons nested below it. Clicking the group icon lying in a file or folder’s row will create a modal popup that allows the operator to view an object’s access controls, such as who has full control of that object. This empowers operators to find avenues of exploitation by finding files and folders with weak permissions, which solves the second problem in our problem set. The image below shows the modal popup that’s returned with the verbose access control information.

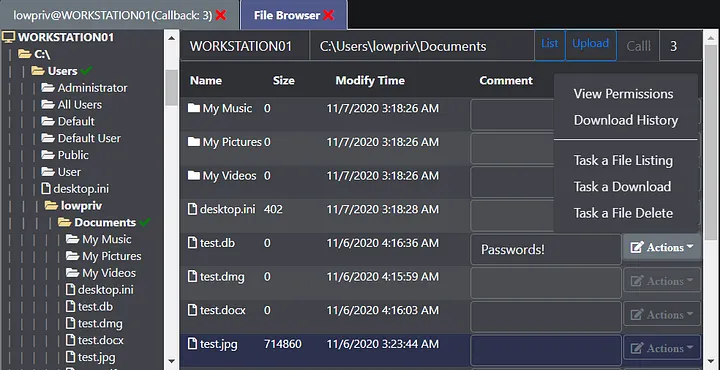

Lastly, while we have made significant improvements on the output of the command itself, users may still wish to browse files and folders using a more traditional GUI that mimics an application like explorer. Apollo interfaces with the APIs of Mythic that do just that when reporting output of the “ls” command, allowing you to open a more familiar file browser to navigate through. This can be accessed by clicking the small dropdown next to the keyboard interactive icon of a callback and selecting “File Browser.”

In the image above, we can see the full directory structure of computer WORKSTATION01 on the left-hand side. We can expand and collapse folders in this tree listing by clicking their associated icons, whose coloration determines if their contents have been listed in the past. Mythic’s file browser data is stored server-side, meaning that each operator that views the file browser will see the same results regardless if they’ve performed any directory triage in that session. Moreover, on the righthand side, we see that we can take a variety of file actions directly from the UI, and even store comments on files and folders that appear interesting (such as noting a database contains passwords). While the file browser is not extensible through browser scripting, it is still an extremely powerful alternative to the traditional Apollo tasking output.

Process Triage

Traditionally, process listing output from agents has been frustratingly scant. A bare-bones listing telling you a process’s ID, its parent’s ID, the architecture, and the name; but how does a user find process outliers on that information alone? When Seatbelt was released, it attempted to solve this problem by displaying all non-Microsoft processes; but a process is more than just a name.

Apollo attempts to aid in searching for interesting processes by implementing two versions of process enumeration — a lite version, which is the traditional, bare-bones listing, as well as a full version, which retrieves information such as company name, description, integrity level, and more.

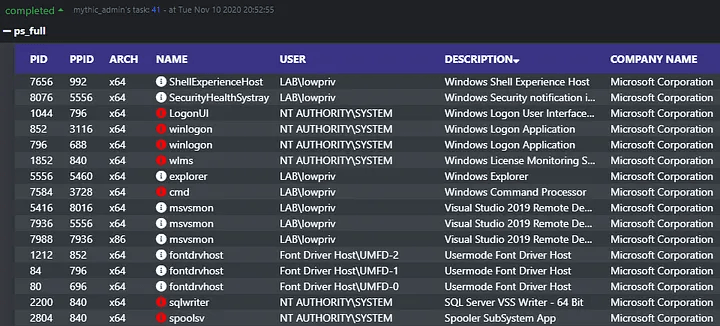

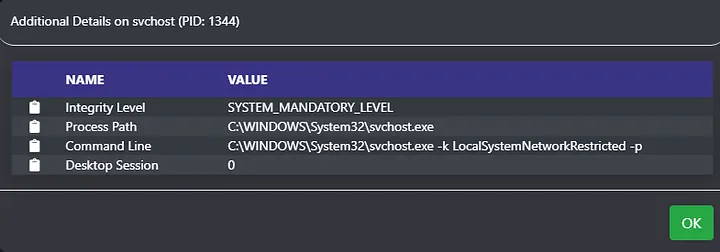

Now, instead of running Seatbelt, an operator can issue a ps_full command to retrieve a more verbose process listing. Sorting by company name or description makes it easy to find outliers in the process list. Moreover, you’ll notice the white or red icon next to the process name, which indicates whether the process is running as a MEDIUM_MANDATORY_LEVEL or as a HIGH_MANDATORY_LEVEL/SYSTEM_MANDATORY_LEVEL respectively. Clicking this icon retrieves additional information about a process that includes its integrity level, full path, command line, and desktop session, as shown below.

Providing the full process path and command line allows students and operators to understand the running process on a computer more easily and can point them to potentially interesting files and folders Finally, it allows them to make smarter operational security decisions regarding post-exploitation jobs and better blend in with their environment.

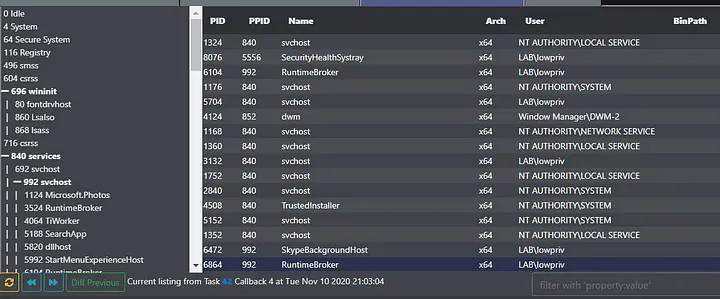

Lastly, the “ps_full” command interfaces with Mythic’s built-in process explorer, allowing you to see process trees in a graphical format. You can access this view by clicking the drop down arrow next to the keyboard interactive icon of a callback and clicking “Processes”.

User Exploitation

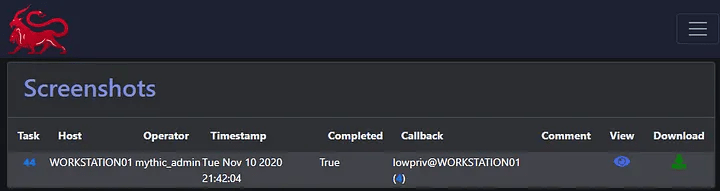

Apollo interfaces with Mythic’s keylogging and screenshot operational views, which provide a 21st-century interface to view this information.

Screenshots

For screenshots, you’re able to see at-a-glance what task initiated the screenshot, what user context the screenshot executed within, and are able to see a preview of the image by clicking on the eye icon on the right hand side of the screen.

Keylogging

Apollo’s built-in keylogger is based on a previous project of mine called WireTap, which monitors keystrokes, translates corresponding key combinations, monitors clipboard activity, and reports back the window in which the activity occurred.

When this existed as a separate .NET assembly, this output was spooled to both standard out and to a file for later parsing. With Mythic, this processing is done for us, so that our main operational view remains uncluttered while the server processes keystrokes based on computer, user, and window title in that order.

Clicking the clock next to any one of the window titles will show the date time in which the keylog was received, and clicking on the window title itself will expand or minimize output relating to that window. If a user were to switch between several windows, say start typing in PowerShell, tab to their browser to google, and then switch back to PowerShell, all PowerShell keylogs would be consolidated under the PowerShell window title instead of being displayed in the order of which they were received. Doing so makes it easier for an operator to distill this information into their respective buckets and find interesting applications that the user has interfaced with over the duration of the keylogging job.

.NET and PowerShell Script Workflow

Apollo supports third party .NET assembly and PowerShell script execution through the following commands:

- assembly_inject

- execute_assembly

- register_assembly

- unload_assembly

- psimport

- powershell

- powerpick

- psinject

- psclear

Because the web browser does not have access to the file system, .NET assembly and PowerShell script execution is broken up into two components: registration of the file and execution.

A file is registered through the “psimport” and “register_assembly” commands. There is no file limit on the size of assemblies and PowerShell scripts imported this way. Once registered, the assemblies are cached in the agent for subsequent execution. Apollo streams output from all commands, so if an operator executed a long-running script like Inveigh, output would be consolidated in a single task output window. Additionally, the agent can cache multiple scripts and assemblies simultaneously. Listing scripts and assemblies can be done via “list_scripts” and “list_assemblies” respectively. Below shows Apollo executing a custom script and “Get-DomainUser” from PowerView in the same “powerpick” tasking.

Lastly, for “powerpick”, “execute_assembly”, “mimikatz”, and other unmanaged commands, injection will be performed using Apollo’s built-in injector. The injector determines what injection technique is used in certain post-exploitation jobs, and the operator can dynamically set the injection technique in use even after the agent has been compiled.

In trainings, we can utilize this dynamic injection to show how one type of injection could be detected by an endpoint product, while another could potentially evade it. Currently, only two injection techniques are built-in to the agent: Early-bird Queue User APC and Create Remote Thread. The below image shows how one can modify the injection technique on-the-fly.

Credential Management and Token Manipulation

Educating students on the intricacies of Windows authentication is one of the most complex topics we ask students to grok in our Adversary Tactics: Red Team Operations course. Primary tokens, thread tokens, user impersonation, and otherwise can be hard for someone new to the space to fully understand. Moreover, when a student asks for help, it can be hard to diagnose in what ways they have tampered with or manipulated their primary token, confounding whatever resource access issue we’re attempting to debug.

As such, Apollo implements its own suite of credential management commands that track what user context is being used in both local and remote operations. This tracking is in place for all the usual suspects: “rev2self,” “steal_token,” “make_token,” and “pth,” with an additional command “whoami,” which returns what tokens are currently in use for the agent. Below shows that system in action.

Payload and Artifact Tracking

Too often, students and operators alike will run commands from their agents without thinking of the OPSEC considerations of running those commands. Through both Mythic’s task creation and artifact reporting, Apollo can keep a detailed account of what payloads were used where, as well as verbosely account for its actions performed in an environment.

Payload Tracking

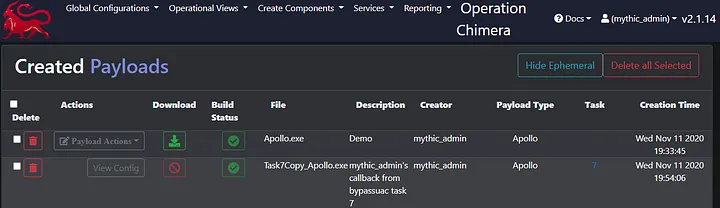

Some post-exploitation activities require additional payloads to be created in order for them to execute. Commands like psexec, bypassuac, spawn, and inject all require an Apollo payload in one form or another. Because Mythic allows us to control how taskings are created, we can create a new payload each time one of these commands is issued. The benefit of this approach is three fold.

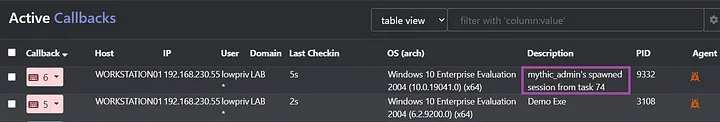

First, by generating a new payload on agent tasking, we can correlate a payload to a given task ID. While this may seem minor, let’s do a case study on the spawn command. When students are ready to begin operating, one of the most common pain points is deconfliction amongst themselves — who is operating on what callback, and how can I keep track of that? Apollo leverages this dynamic compilation to modify parameters of the generated payload to ensure that certain attributes, such as the description of the payload, contain identifying information about its origins.

As you can see above, the new callback details what user issued the task and what task dispatched its creation.

Second, with the creation of new payloads on command tasking, we can leverage Mythic’s built-in artifact tracking to track where payloads are in use. If a payload were to be detected somewhere in the environment, we’d know exactly what payload it was, its configuration, and what task issued its creation.

Lastly, while Apollo does not leverage this feature, one could leverage this building pipeline to perform pre and post processing on generated payloads. In the case of psexec, you could imagine that the service executable generated is responsible for executing shellcode. If you control the service executable generation and the nested payload generation, you could encrypt the embedded shellcode with a unique key per-tasking. You could generate a new pre-shared key per-payload generated. The options are limited only to your creativity.

Artifact Tracking

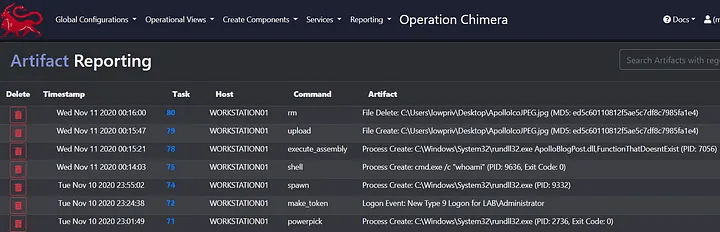

During an assessment of any type, it can be easy to let your operational cadence and security slip. The rate at which someone is entering commands is getting fast and loose, processes are being spawned and injected into, files are being uploaded, moved, deleted, and renamed — all without a verbose and easily searchable log of these activities.

Enter the Reporting Artifacts view. Reporting artifacts allows us to account for all of our post-exploitation activities, with the additional functionality of filtering artifacts using regular expressions. Currently, Apollo reports back the following artifact types:

- Process Create

- File Write

- File Delete

- File Move

- New Logon

While this is a fantastic tool for operators, specifically it allows us to educate our students on the impact and tradeoffs one must think about when executing commands. For example, should rundll32.exe be interacting with LSASS? Is a domain administrator logging into a workstation an anomalous occurrence? When in the operation did it occur, and for what purpose? Artifact tracking empowers us to answer all of these questions and more.

Conclusion

In this article, we’ve covered a few some of the ways Apollo and Mythic solve operator dilemmas and improve their work flow; however, this is just the tip of the iceberg. With well over sixty commands and counting, there’s simply too much to cover in one article. Moreover, with Mythic’s flexible and developer friendly design, rapid development of new communication profiles, modules, and payload wrappers are on the imminent horizon. Just like every great myth, Apollo will only get better with time.

Additional Resources

- Apollo Repository: https://github.com/MythicAgents/Apollo

- Mythic Repository: https://github.com/its-a-feature/Mythic

Use Apollo in Upcoming Training Offerings