Mapping Deception with BloodHound OpenGraph

TL;DR As defensive postures continue to mature, deception technologies provide organizations the opportunity to harden defenses and take a more proactive approach in securing their environment. In large enterprises, it can be difficult to determine where and how to deploy effective deception techniques which are discoverable and believable for attackers. By utilizing OpenGraph, we can visualize attack paths in both AD and third-party technologies. Using OpenGraph can be beneficial for planning and understanding potential deception paths, utilizing a small utility like deceptionClone can help with this process.

Intro

Deception can be many things, but at its core, deception is a good lie. In cyber security, we see deception take the form of canary tokens, honey pots, honey accounts, etc. We use these tools to catch someone doing something they shouldn’t. Deception has some clear advantages over a typical detection or rule. First, a good deception can be incredibly high-fidelity; if there is no legitimate use for deception artifacts, any attempts to use them are very likely malicious. Second, defenders can funnel attackers from across their environments into detections via attack paths.

I believe most, if not all, environments can harden their security posture by implementing some form of deception. And while deception isn’t anything new or groundbreaking, I want to talk about effective ways to implement deception in your environment. Also, a huge shoutout to my manager, Josh Prager (praga_prag), for helping with this blog. He was a great sounding board and helped rein in my ramblings into something cohesive.

Creating Effective Deceptions

Deception needs to be highly specific to the environment where it is deployed. When we begin to consider what our environment looks like from an adversary’s point of view, we need to consider attack paths. If you aren’t familiar with attack paths, I’ll refer you to a great article by SpecterOps outlining attack path management. From the first line of the article,

Attack Paths are the chains of abusable privileges and user behaviors that create direct and indirect connections between computers and users.

Realistic deceptions exist within attack paths, so we need to put on our adversary hats and think like an attacker.

Looking at the existing attack paths in your environment is a crucial first step in building deception. It is very likely you have some kind of attack path in your environment; whether you are aware of it is another issue. Using tools like BloodHound, we can generally get a sense of where our attack paths lie within Active Directory. With the launch of OpenGraph, we can now expand our attack path management to the zeitgeist of third-party technologies across our enterprises.

Not familiar with OpenGraph? I’ll refer you to this article by Andy Robbins which covers it in depth. TL;DR OpenGraph allows us to collect and model attack paths in pretty much anything.

Ideally, once we identify an attack path within our environment, we remediate it. Whether it’s locking down permissions, removing old technologies, or modifying polices, in many cases it’s for the best. However, there are times when we just can’t. Whether it’s business justifications or technical debt, there are plenty of reasons why an attack path might be irrevocable. In these instances, deception is a great way to harden our security posture utilizing our known soft spots.

Alternatively, if we can remove an attack path, that’s great…but what if we turned it into a deception attack path instead? Not only would we remediate an existing issue within our environment, but we would also be creating a high-fidelity detection opportunity. We also know that it looks very realistic to an attacker because, at one point, it was.

By attack path mapping our deception technologies, we can overcome the issues of discoverability and context. If we can map the deception through reconnaissance, we know an attacker can also find the deception. It is then up to us to incentivize them to use this deception along the attack path. This then creates context. Our piece of deception becomes a crucial step or objective for an attacker to compromise or interact with. This allows us to funnel attackers into our deception technologies, ideally from anywhere within our network.

Building Attack Paths

If you haven’t read this article by our Vice President of research, Elad Shamir, check it out. His article talks about the Clean Source Principle (CSP) in relation to attack paths. For those unfamiliar with the Clean Source Principle, it states:

All security dependencies must be as trustworthy as the object being secured.

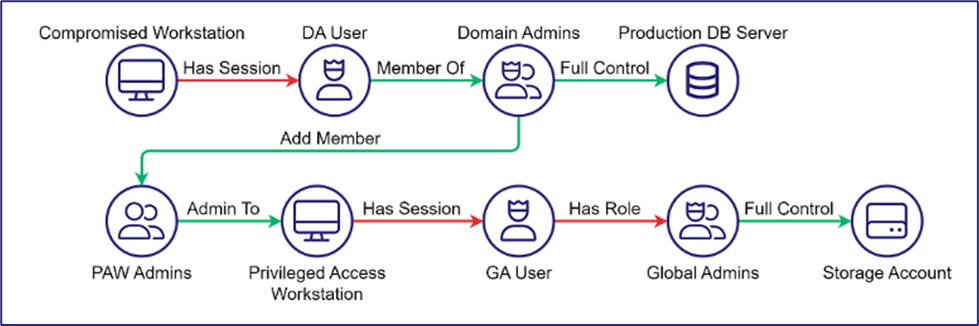

In our example above, the most basic violation is the Domain Admin User has a session on the Compromised Workstation. Assuming the workstation is not a Tier Zero asset, the Domain Admin’s session on the workstation violates the CSP. I really recommend reading Elad’s article, as it goes into more depth and ties CSP into Identity tradecraft.

The Clean Source Principle can help guide us in creating attack paths within our environments which are believable and tempting to attackers. Utilizing BloodHound and OpenGraph, we can map these attack paths across technologies and expand our deception capabilities.

F4keH0und and AD DS

While writing this blog, DEF-CON Group 420 released F4keh0und and I wanted to shout out another great deception project focused on reviewing Active Directory data from BloodHound’s SharpHound output. F4keh0und is a PowerShell module which analyzes things like BloodHound data and finds opportunities for deception. You can find out more info on the GitHub project, but we wanted to cover another great deception solution as deception technology adoption continues to gain momentum. Another big thanks to Josh Prager for putting in the majority of the work creating this section.

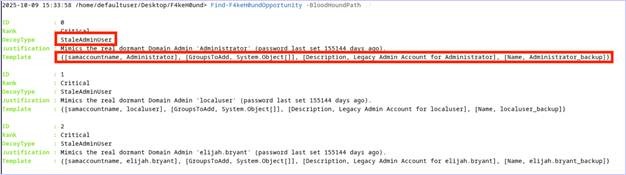

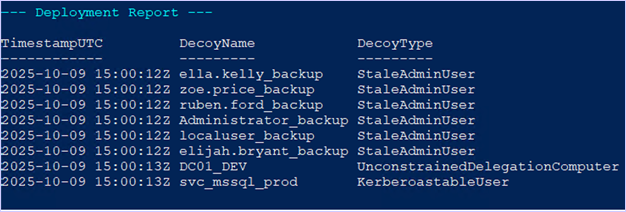

Defenders interested in analyzing their Active Directory environment data for deception solution opportunities can run the following PowerShell cmdlet from the F4keH0und project, New-F4keH0undOpportunity. In the example below, after running the cmdlet, we can see several accounts that can be copied and added to the Active Directory environment.

Defenders can take the output from the New-F4keH0undOpportunity cmdlet and then deploy these deception solutions into the Active Directory environment with a privileged user.

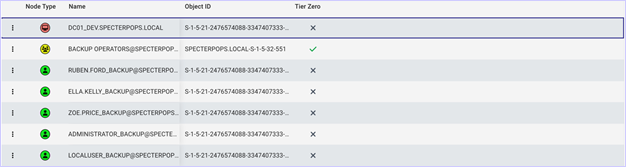

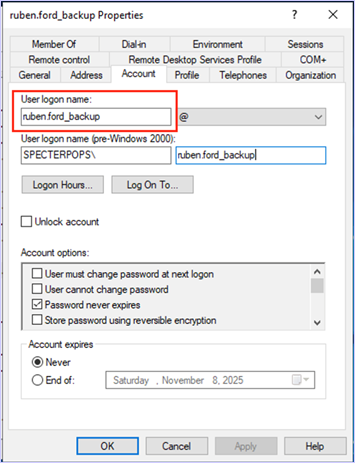

The output will display the copied user accounts as “_backup” StaleAdminUser accounts within Active Directory. After deployment of the deception solution cloned accounts, we can collect the LDAP data via SharpHound and review the attack paths that the deception solutions are part of.

Each account F4keH0und generates will be disabled, will not have any rights that enable attack paths, and will not have system ACLS (SACLs) enabled by default. Administrators can enable the deception solutions and add custom SACLs to these objects. In most cases, “Full Control” auditing can be enabled on the objects since ideally, these objects should not be accessed legitimately for any reason.

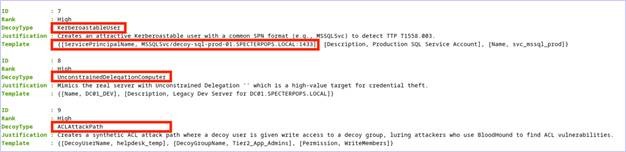

Defenders will likely have to create an attack path with the canary accounts as they do not automatically deploy with privileges to be revealed by attack path enumeration. In the below example, we added the canary backup accounts to a group with GenericWrite over the canary DC, DC01_DEV.

This introduces a very real attack path, but with auditing enabled on the DC01_DEV’s “KeyCredentialLink” or “AllowedToActOnBehalfOfOtherIdentity” attribute to generate an Event ID 5136 (i.e., “A directory service object was modified”) upon attribute modification, defenders can identify the abuse of the shadow credentials attack path. This attack path is not generated by the F4keH0und tooling but can easily be generated with some minor modifications to the deception solution attributes. From an attacker perspective, this attack path will be an enticing target for which to try and abuse.

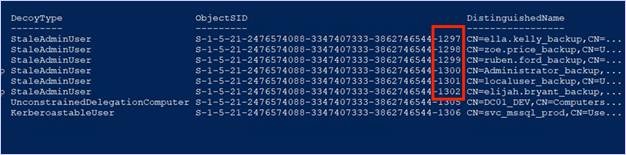

Something to note when deploying the cloned account deception solutions, the decoys are incrementing the RIDs generated by 1. From an attacker’s point of view, these may stand out as strange; as these accounts were supposed to be stale and old, yet the RID is newer (Shoutout to JD Crandell for noticing this).

An alternative to creating new objects may be to use F4keh0und to identify existing objects providing the opportunity to turn them into a decoy. Old accounts from resigned employees are a great example; we can turn these accounts into deceptions by making some modifications to make them enticing from an abuse point of view while retaining their realism. This method of converting older or known stale accounts into deception solutions is a classic tradecraft method called “recycling” Active Directory objects.

Deception Considerations

In the previous section, we looked at adding a shadow credential attack path to our environment for the purpose of deception. Although the attack path was intentional, the risk of abuse is still very real. When we introduce abuseable attack paths for the purpose of deception, it’s important to acknowledge and consider the risk involved. If the attacker does attempt a shadow credential attack, they will raise an alert; however, they likely now have gained privilege escalation within the environment. Therefore, it is now solely the duty of the responding party to act quickly and properly triage the alert.

However, we don’t always need to introduce real attack paths into our environments for the sake of deception. A good example of this is the Certiception project. Certiception is an example template which is vulnerable to the AD CS ESC1 attack. The project is based on the TameMyCerts policy module, which allows additional control over certificate requests. In this scenario, you may deploy a template seemingly vulnerable to ESC1, but block it at the CA level with TameMyCerts. The risk introduced into the environment is minimized because a certificate cannot be issued using the template due to the policy module. However, from an attacker’s point-of-view, the template looks abuseable and there is not an easy way to determine if the template is a deception (that I’m aware of).

As you consider deception within your own environment, it’s really important to understand the risks involved. In many cases, we can mitigate additional risks being introduced by neutering attacks, like with TameMyCert. In other cases, we may be building deceptions which introduce real risk. In these cases, robust playbooks should accompany these alerts providing insight into all the immediate steps needed to limit exposure caused by the attack. Additionally, defenders triaging the alerts must be highly aware of the fidelity and nature of the deception specific detections. Knowing what objects are affected and where attackers may move next are pivotal for creating a robust response playbook, BloodHound can be very useful for these purposes. When implementing deceptions outside of Active Directory, OpenGraph can help provide similar context to deceptions we deploy outside of Active Directory, helping us better understand the risks involved.

Deception with OpenGraph

We’ve covered some of the thought process and implementation of deception technologies utilizing F4keH0und, so now let’s turn our attention to OpenGraph.

A benefit of mapping our deception technologies is overcoming the issues of discoverability and context. Haphazardly throwing deception technologies within our networks and on endpoints is a disservice to deception. This is taking a “needle in the haystack” approach to our deployment. How do the attackers know to find credentials.txt on Sally from accounting’s workstation if they land on Bill the developer’s workstation? Do attackers really port scan entire networks leading them to your honeypot machine with SSH anonymous logon? Maybe, but sophisticated threat actors and red teamers know better. They know a port scan of your entire network will raise other network monitoring alerts, negating the need for deception to address this kind of activity. If we can map the deception through modern attacker reconnaissance methods, we know an attacker is likely to find the deception. It is then up to us to incentivize adversaries to use this deception along the attack path. This creates context. Our deception becomes a crucial step or objective for an attacker to compromise or attempt to abuse for moving or escalating within our environment. This allows us to funnel attackers into our deception technologies from across our network utilizing various technologies.

deceptionClone, a Small OpenGraph Utility

When interacting with various OpenGraph projects with the aim of modeling deception, I found myself wanting to add deception-specific nodes and edges or label existing nodes as deception. This resulted in a small tool, deceptionClone, which can help model various deceptions in OpenGraph.

deceptionClone is project agnostic, allowing you to manipulate nodes and edges from any OpenGraph project. For example, if you’ve deployed deception within your environment and want to ensure that others looking at attack paths know that the asset is a deception, we can label that existing node as such.

Additionally, if you are trying to map out deception within your environment, you can add nodes and edges dedicated to deception and model it within BloodHound without deploying any technologies.

Lastly, the project has the functionality to merge OpenGraph projects together. In a later example, we’ll look at merging a GitHound collection with an AnsibleHound collection. This can be helpful to model deception attack paths across technologies and expand OpenGraph’s modeling abilities.

Currently, functionality is limited to visualizing attack paths within BloodHound; this leaves the heavy lifting of deception deployment up to you. Adding the ability to deploy deception technologies via OpenGraph maps would be an incredible addition for anyone looking for a project.

There is a caveat to merging projects together, which mainly revolves around unique object IDs and resolution across projects. The main use-case I was aiming to solve was seeing how one attack path connects to another path across technologies. In this scenario, I already knew the nodes in each project which represented the same object. Since IDs need to be unique, the ID collision needs to be addressed. I wanted to keep the nodes separate from their respective original graphs, so an “is” edge represents the link. To deal with the duplicate ID, all the references to the ID in one of the graphs need to be modified. This shouldn’t affect path finding, but a new collection will not align with the previous collection, as the object ID for the colliding object has been modified.

In the case of the same node having two separate objectIDs from two different OpenGraph collections, we need to correlate those IDs. The tool takes correlated IDs via CSV or command line which allows the correlation of the object IDs and creates the appropriate edges.

However, this raises the question: “How do I know what objects are correlated?” Since this was primarily aimed at deception, I don’t have a particularly great answer. As the OpenGraph library expands, a solution may naturally arise; or someone smarter than me will figure it out and roast me (as they should). And who knows? It may already be in the works 😉.

I’ll run through a basic example, straight from the GitHub Readme, and then we can look at some real OpenGraph implementations.

deceptionClone Examples

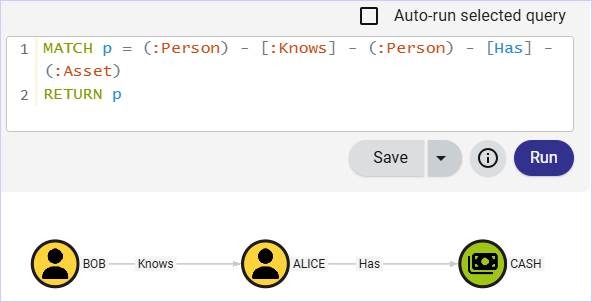

Using a minimum OpenGraph implementation, this example adds a deception node and edge. The example data can be found under the examples folder. To get our icons to show up as Font Awesome icons and not “?” marks, we can use the following command to load the icons:

python deceptionClone.py register-icon --url http://127.0.0.1:8080 --token <TOKEN> --type Person --icon user --color #FFD43B

python deceptionClone.py register-icon --url http://127.0.0.1:8080 --token <TOKEN> --type Asset --icon money-bills --color #a0c615Using the example data, we can use the sample query to see our graph:

MATCH p = (:Person) - [:Knows] - (:Person) - [Has] - (:Asset)

RETURN p

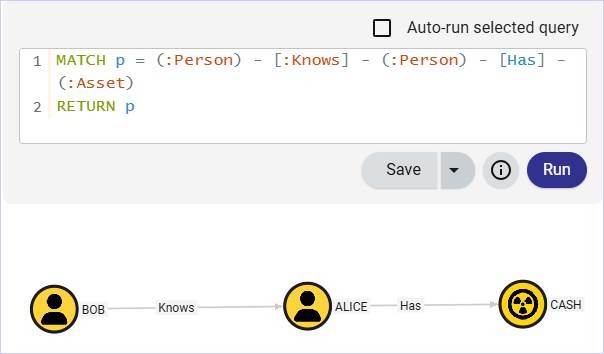

Now we want to bring some deception into the mix. In this example, let’s say that Alice’s cash is the deception; we want to map if Bob is trying to “Know” Alice for her “Cash”. To do this, we can use deceptionClone to convert the existing Cash node to a deception node.

python deceptionClone.py --in example_data.json --out deception_example_data_1.json decept-node --id 567 --name cash --deception-kind Deception --description "Finding out who my real friends are"To load our deception Icon, we can run the following:

python deceptionClone.py register-icon --url http://127.0.0.1:8080 --token <TOKEN> --type Deception --icon circle-radiationNow the Cash node is labeled as deception.

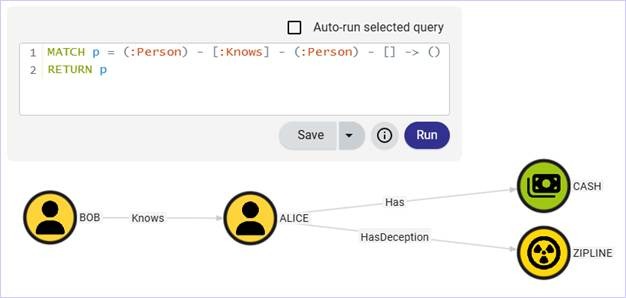

Okay, but what if we wanted to keep the existing Cash asset as-is and introduce a new deception in the form of a sick zipline? This way Alice can see if Bob only wants to know her for the zipline. We can keep the existing paths and add a separate edge/node easily.

python deceptionClone.py --in example_data.json --out deception_example_data_2.json attach-deception --id 234 --name Zipline --description "feels like Bob is just here for the zipline"A basic query to show the newly added zipline asset.

MATCH p = (:Person) - [:Knows] - (:Person) - [] -> ()

RETURN p

Now that the basics are covered, we can start getting into some more interesting OpenGraph data and explore some additional features, like merging graphs.

Deception Placement

In our previous example, we used F4keH0und as our method to identify opportunities for deception. Another way to source deception solutions is from a red team or threat intel reports. Utilizing attack paths which were abused within your environment are likely to be very powerful. Since, if a red team already abused the attack path, it’s identifiable and contextually relevant to attackers. Additionally, since it was your environment, it’s highly specific and not some off-the-shelf solution. Threat intel reports may provide additional inspiration, taking note of what threat actors may be abusing and seeing if those attack paths are applicable to your environment.

For example, on a recent assessment we compromised a developer’s GitHub credentials via phishing and abused credentials stored in GitHub artifacts. GitHub telemetry is somewhat lacking and it was difficult for defenders to identify this activity or build alerting around it: a great opportunity for deception. When telemetry or logs are simply not robust enough or accessible to write alerts, deception can provide coverage.

Some of the credentials found in the artifactory allowed us to interact with cluster management and orchestration technologies, facilitating additional opportunities to pivot and potentially execute code. Drawing inspiration from this operation, I chose to outline some deception solutions in GitHub and Ansible loosely based on our assessment’s attack path.

GitHound Example

If you haven’t seen the new GitHound project, it’s a great addition to the OpenGraph family. GitHub is everywhere. In a couple of recent engagements, GitHub was a crucial step in gaining a foothold within the environment and facilitated most of the achievement of various objectives.

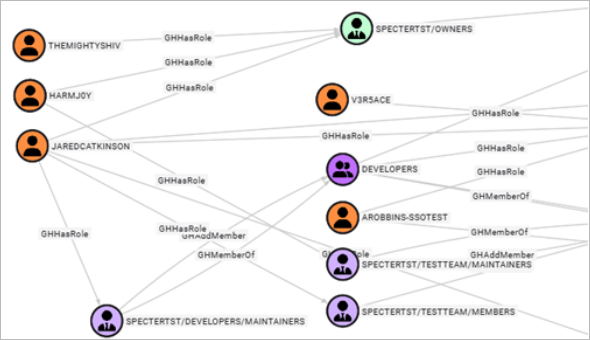

Attackers commonly target developers, as they typically have elevated privileges and access to juicy things like GitHub. Using GitHound, we can get a sense of where attack paths exist in our GitHub environment and build deceptions in or around them.

GitHub is a great place to keep code. Developers also love to store credentials with their code. So, let’s consider the humble canary credential. The honey credential is powerful but misunderstood. Throwing them haphazardly on desktops is a disservice to the true potential they may have.

If you have an internal red team, or access to a recent assessment, I’d highly recommend reviewing it and considering the attack paths outlined. Better yet, have a chat with your local adversary simulator and pick their brain about potential attack paths they see in your environment.

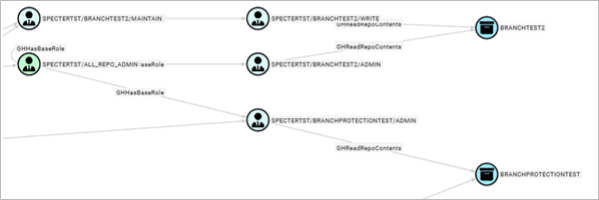

So, let’s expand on the basic idea of canary tokens and implement a deception path focused on a secret leaked on GitHub. I’ll be using the example collection data found in the GitHound repo. The following cypher gives us an idea of what users can read repositories within GitHub.

MATCH u = (:GHUser)-[:GHMemberOf|GHAddMember|GHHasRole|GHHasBaseRole|GHOwns*1..]->(:GHRepoRole)-[:GHReadRepoContents]->(:GHRepository)

RETURN u

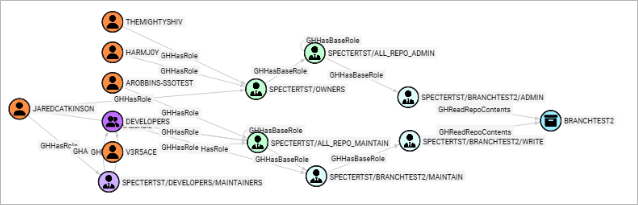

The resulting graph is a bit large for a screenshot, but we can see five users have access to a couple of repos. This may seem trivial, but like AD groups, GitHub teams and roles quickly become nested and determining who has read access to a repository may not be clear. In a large collection, this graph would likely be even bigger and messier. So, starting with a query for groups containing the word “dev” or “ci-cd” may prove more useful.

With a vague path from a user within a group to a read repo, we can begin to build our deception. Secrets placed (sensitive dependency) in a readable repo (untrusted source) creates a CSP violation. Putting cleartext credentials in a readable repo is kind of vanilla (though I’ve seen it plenty in production environments). Let’s use GitHub Actions instead.

Currently, GitHound doesn’t support GitHub token permissions (yet), but we can use the GHReadRepoContents as a jumping off point. Looking at our Groups with “Read” access to repositories, we could add a honey credential to “BRANCHTEST2” artifacts. Artifacts are the byproduct of GitHub actions and may leak credentials used in CI/CD pipelines. Credentials in artifacts, to my knowledge, are not subject to GitHub’s secret scanning. This will take some architecting with your CI team, but hopefully a nice OpenGraph visual aid will assist in the process.

A query to show our targeted repository where we want to add our deception.

MATCH u = (:GHUser)-[:GHMemberOf|GHAddMember|GHHasRole|GHHasBaseRole|GHOwns*1..]->(:GHRepoRole)-[:GHReadRepoContents]->(:GHRepository {objectid: "R_KGDOM3LDJG"})

RETURN u

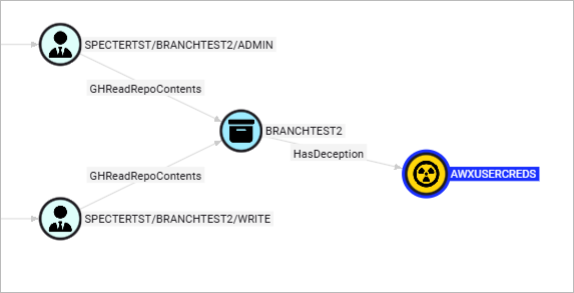

Though simple, one of the best parts about using OpenGraph to visualize our deceptions is answering, “Where is it?” Using the tool to make a slight modification to our existing attack path, we can load a new deception node and edge into our attack path.

python deceptionClone.py --in github_example.json --out github_deception_child.json attach-deception --id R_kgDOM3LdJg --name AWXUserCreds --description "Ansible credentials in artifact upload"By adding a small modification to the previous Cypher, we can see our deception in BloodHound.

MATCH u = (:GHUser)-[:GHMemberOf|GHAddMember|GHHasRole|GHHasBaseRole|GHOwns*1..]->(:GHRepoRole)-[:GHReadRepoContents]->(:GHRepository) - [:HasDeception] -> (:Deception)

RETURN u

Communicating where the deception is and who has access to it becomes much clearer. We also know that the initial information is reliable, as it was collected from our own environment; this helps reduce the risk of introducing unintentional abuse vectors into our networks while planning deception.

In this scenario, if we can read the artifacts, we may be able to dump infrastructure as code files, like Terraform state files, which may be uploaded to Artifactory during the build process. If you aren’t aware, Terraform state files can be full of credentials; as environment variables or secrets are pulled from key vaults, they are loaded into the state files and potentially stored in cleartext or Base64.

For our deception path, we can place some CI/CD credentials within the TF state files as our honey credentials. Setting up monitoring of the credentials is then critical to catch attempted abuse. But we won’t stop there, we can continue to build upon this deception attack path using another OpenGraph project, AnsibleHound.

AnsibleHound Example

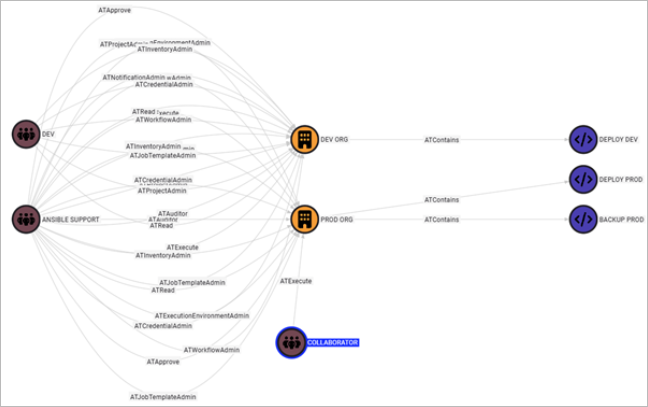

Developed by @romereik and @s_lck, AnsibleHound is an OpenGraph collector for Ansible WorX and Ansible Tower. Ansible and Terraform go hand in hand. As your CI/CD deploys infrastructure, Ansible is a way for your DevOps team to set up and manage the deployed infrastructure. As an attacker, this is an attractive technology. Credentials and privileged users are commonly required to configure machines; additionally, there is typically a lack of AV or EDR solutions present on these boxes.

In our current example, the adversary hasn’t had a need to be on our internal network. GitHub access may have been compromised by a personal access token found in a developer’s personal repository, or perhaps a GitHub CLI phish landed them API access. A next logical step would be to attempt to pivot to the internal network. A leaked Ansible Tower credential would be a great way into the network.

Though access may be limited to a containerized build, there’s potential for discovering additional credentials, moving laterally between machines, and container escapes. Using the example data from the AnsibleHound repo, we can see the users in both Dev and Ansible support have the ability to execute and modify templates due to their admin status.

MATCH u=(:ATTeam)-[ATExecute*1..]->(:ATJobTemplate)

RETURN u

We’ve got plenty of options as far as how to build our deception. A major consideration is to think about what additional risk may be introduced. Adding additional users with access to something like the collaborators Team may introduce real risk if they can modify the templates as outlined above. Another option you have is standing up a completely faux deploy for the deception use-case. Since the compromise of this deception path would potentially result in remote code execution, we’ll set up a separate deception attack path.

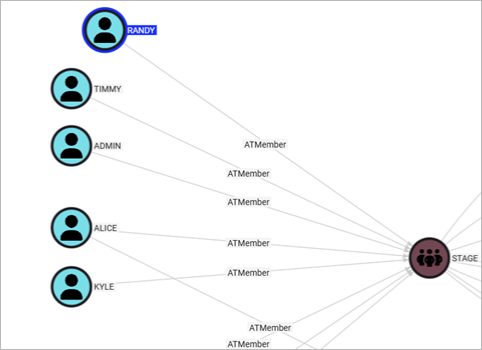

First, we can add a new user, Randy, to our STAGE group.

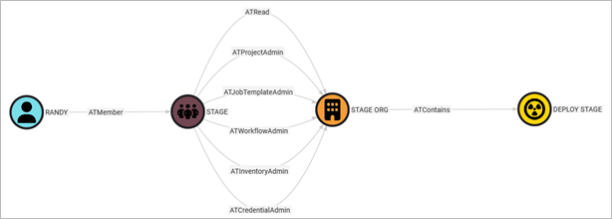

Then, we can add the DEPLOY STAGE job template to the STAGE ORG. Utilizing a cypher query, we can see the newly visualized attack path from the deception user RANDY to the deception job template.

Assuming we have enabled Ansible logs, we can write a detection around our user (or any user) making changes to the new template we’ve configured. We can write a detection to ensure we catch any attempts to modify this template, as there is no legitimate reason for users to modify the plan.

Merging Graphs

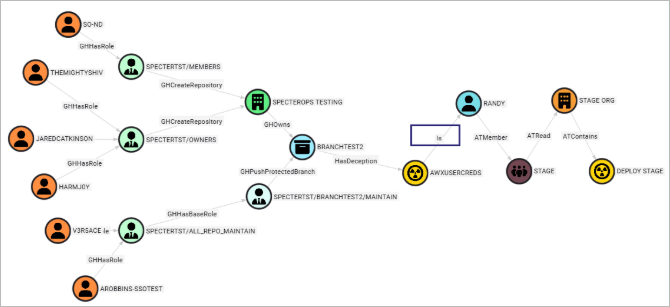

We’ve got two deception attack paths visualized in BloodHound, but what if they are part of a larger path? Using the merging capability, we can combine the two graphs we generated and visualize the whole chain.

In our examples, we have AWX credentials exposed in GitHub. So, let’s say the AWX credentials are for the Randy user we created for Ansible. Therefore, a compromise of the AWX credentials would create an attack path that hops from GitHub to Ansible; by gluing our two graphs together, we can visualize this.

As previously mentioned, gluing graphs together requires us to know which objects to correlate for us to jump from one collection to another. This is an issue for broader attack path collection and analysis, as we don’t always know how or what technologies are related and may allow a user to jump into another technology.

Another thing to note is that since we create a new graph with a different “source_kind,” we lose the ability to search by “kind” in some instances. The limitation comes from the fact that a node can only have three “kinds,” including the “source_kind.” So, if an existing node has three kinds, when it is merged, it will lose one of the kinds. Currently, we drop the last value in the array; the reasoning is the first kind is responsible for displaying the icon, so it is probably important. In other projects, the last “kind” value is the “source_kind” and duplicative.Okay, back to graphing. Using the following command, we can merge our two deception graphs. We supply the correlation object IDs here, but if there were many, we could use a .csv file instead.

python deceptionClone.py merge-graphs --graph1 ./examples/gluing/github_graph.json --graph2 ./examples/gluing/ansible_graph.json --correlate R_kgDOM3LdJg::DECEPTION,randy-user-0001Now, we can do a Cypher query for the path from a GHUser to an ATJobTemplate.

MATCH p = shortestPath((:GHUser) - [*1..] ->(:ATJobTemplate))

RETURN p

The attack path now accounts for the complete path, across technologies; we can see the “Is” edge links our AWX deception to the RANDY user. In theory, we could continue to merge graphs, granted that we can keep track of our correlation ids and limit kinds to three.

Closing Thoughts

In one of our examples, we looked at a couple of deceptions placed along an attack path spanning two technologies. You might be asking, “why?” Granted we write a detection for the first, wouldn’t the second be a moot point? While that very well may be the case, a single detection may prove quite brittle. Accidents happen, SOC queues become long, response time may not be quite as quick as we’d hoped. Additionally, we now have a fair idea of where the attacker will go next. This not only provides additional time for remediation, but places to look for attacker presence. Lastly, we attempt to minimize the damage the attacker does while tricking them into a false sense of pwnage. The greater the dwell time where an attacker feels undetected, the better. Depending on their motives, they may move to destructive tactics if they feel they’ve been detected. The more sophisticated the attack path, the less likely an attacker will catch on to our tricks. This is why building robust deceptions via attack paths is a powerful tool defenders can employ.

From a red teamer’s perspective, deception technologies scare me (in a good way). Navigating modern networks is already rife with difficulties for attackers, ever-increasing EDR capabilities, network segmentation, deep packet inspection, password vaulting, conditional access policies, the list goes on and on. The modern adversary needs to be highly skilled and resourceful.

A colleague at SpecterOps was on a recent engagement soliciting advice for some issues related to ESC1 abuse. It seemed like the attack should work; however, they were getting a “Denied by Policy Module” error. Had the client published a deceptive template using something like Certiception? Or, was it a tool issue? While troubleshooting, another colleague mentioned CA authorization signature key size defaults in Certify. Do you risk another request if we suspect the template is a deception? Also, if it’s a deception, there’s an alert being triaged and we may be minutes away from deconfliction. That introduces even more uncertainty and potential for wasted efforts via attempts to save the network foothold. In the end, the issue was due to insufficient extended rights on the template, but maybe next time it will be deception.

This simple example demonstrates the power of deception technologies. Deception instills doubt and uncertainty in attackers, slowing them down and complicating trivial or common attack primitives.

OpenGraph for BloodHound facilitates the ability to map various technologies beyond Active Directory. As the possibilities of attack path mappings grow, we hope defenders see the value of OpenGraph for deception mapping. Using attack paths and the CSP, defenders can create realistic deceptions that will incentivize attackers. Using OpenGraph to create sophisticated deception paths across technologies allows us to clearly define and communicate where the deceptions exist.

For defenders, deception allows us to bite back at adversaries. Deception creates doubt for attackers, slows them, and provides opportunities for high fidelity alerts. We hope you find these examples and methodologies useful in your own environments as you build deception paths, hopefully with OpenGraph, of your own.