STOP THE CAP: Making Entra ID Conditional Access Make Sense Offline

TL;DR: Conditional Access is powerful but hard to reason about once policies start to overlap. CAPSlock is an offline Conditional Access analysis tool built on ROADrecon that helps you understand which policies apply, which might apply depending on signals during sign-in, and where enforcement falls apart.

What are we talking about?

After red teaming for a while, I’ve noticed that there is almost always a point during an assessment where the focus turns to Entra ID. Users, groups, applications, and service principals have already been enumerated and the remaining question becomes, “How do I get access to an Entra ID-backed resource?”

In practice, that usually means figuring out what it would take to obtain an access token for something meaningful without triggering access controls I cannot satisfy.

At that stage, the work shifts from enumeration to Conditional Access policy (CAP) analysis. I’m no longer just asking what policies exist, but under what conditions they are actually enforced. That usually turns into reviewing policies to identify gaps, weak assumptions, or alternative access paths, such as bypassing multi-factor authentication (MFA) or finding a scenario where MFA does not apply.

There are already phenomenal tools in this space to enumerate and find bypasses in Conditional Access. ROADtools by Dirk-jan is well known and does a great job collecting Entra ID data automatically. Its policies plugin produces a clean HTML overview of CAPs for a target tenant. From a visibility standpoint, that output is excellent. You can quickly see scope, controls, exclusions, and high-level intent.

Figure 1 – ROADrecon Policy Output

Where things tend to break down is the next step. Even with good visibility, I still find myself doing a lot of manual reasoning to answer questions such as which of these policies actually apply to this user? Under what sign-in conditions? What happens if certain signals are not present? At scale, that kind of analysis becomes slow, error-prone, and heavily dependent on mental modeling rather than something deterministic.

Another option is using tools that aim to directly find Conditional Access bypasses, such as FindMeAccess. Those can be useful, but they typically operate by interacting with the tenant in ways that may leave artifacts behind. From a red team perspective, and even from a defensive research standpoint, that is not always desirable. Sometimes you want to reason about policy behavior without generating sign-ins, alerts, or noise for defenders.

Microsoft does provide a built-in “What If” tool in Entra ID, and it is genuinely useful for administrators validating policy changes. The limitation, from an adversary perspective, is that it requires additional permissions to access, which we normally do not have on assessments. It is designed for operational validation, not for exploratory analysis or large-scale reasoning across many hypothetical scenarios.

Figure 1 – Entra ID What If Tool

I wanted something that addressed the pain points I kept running into with all the above. The goal was to be able to:

- Reason about Conditional Access offline

- Simulate sign-in scenarios without touching the tenant

- Make policy behavior explicit instead of implicit

If you can reason about Conditional Access the same way Entra ID does, at least conceptually, you can start asking better questions. Not just does this policy exist, but when would it apply, what assumptions does it rely on, and where are the gaps if those assumptions are not held?

CAP Recap

Before going any further, it is worth doing a quick crash course on Conditional Access. I won’t do a deep dive as there are already plenty of blog posts, docs, and conference talks that cover Conditional Access in detail.

At a high level, Entra ID uses a zero trust policy engine[1]. Access decisions are not based on a single factor, but on a collection of signals that are evaluated together to determine what should be enforced. You can roughly think of this flow as signals being collected, decisions being made, and enforcement happening as a result. More information regarding Conditional Access can be found here.

Figure 2 – Conditional Access Signals

Conditional Access policies themselves are effectively if-then statements. If a set of conditions is met, then a set of controls is enforced. Conditions are built from signals like who the user is, what resource they are accessing, the platform or client app in use, and various risk or device-related attributes. Controls define what must happen if the policy applies, such as requiring MFA, enforcing compliant devices, or blocking access entirely.

One important thing to remember is that CAPs are not evaluated in isolation. When a user signs in, all enabled policies that apply to that sign-in are evaluated. The user must satisfy the combined enforcement of every applicable policy. This is why Conditional Access issues are often the result of policy overlap rather than a single misconfigured policy.

From a flow perspective, a sign-in attempt first results in session context being established. This is where Entra ID gathers details about the sign-in, such as the user, application, device, client app, and any available risk signals. Once that context is established, CAPs are evaluated against it, and enforcement decisions are made.

If any applicable policy results in a block, enforcement stops there and access is denied Otherwise, enforcement continues and the user must satisfy all required controls across all applied policies before access is granted. Peter Van Der Woude also discusses this in depth in his article, “The Conditional Access Policy flow”.

Figure 3 – Conditional Access Flow

Offline CAP Analysis

On the surface, evaluating Conditional Access offline sounds straightforward. You export the policies, line them up against a user and an application, and see what applies. What I’ve found is that, in practice, it gets complicated quickly.

The main challenge with doing Conditional Access analysis offline is that some policy conditions depend on signals that are only determined during sign-in. The policy logic is clearly defined, (e.g., this policy applies to this user accessing this resource) but the outcome depends on signals determined during sign-in. Signals like sign-in risk, user risk, authentication flow, and parts of client app detection are not values you can always know without an actual sign-in happening.

This creates an important distinction that admins often misunderstand. There is a difference between a policy that definitively applies to a sign-in and a policy that could apply depending on certain conditions during sign-in. If you treat those two cases the same, you either end up overestimating enforcement or missing policies entirely.

Another challenge is normalization. Entra ID does a lot of normalization internally before evaluating CAPs. Application names, service identifiers, platform values, and even certain scopes resolve into canonical forms that are not always obvious from the raw policy definitions.

For example, a CAP might target “Office 365” as a cloud app. Under the hood, that maps to a collection of different resource identifiers across multiple Microsoft services. If you evaluate that policy offline using a single resource ID without accounting for how Entra ID groups and normalizes those resources, the policy may appear not to apply even though it would during a real sign-in.

The same issue shows up with things like platform values or client app types, where what is stored in a policy does not always line up one-to-one with how Entra ID evaluates the sign-in context. If you do not account for this normalization step, offline evaluation can produce false negatives where a policy should apply but does not appear to.

There are also Conditional Access constructs that do not behave like simple attribute matches. Exclusions invert logic and can change outcomes. Special values like “All” and “None” are not always wildcards or empty sets. Device filters are expressions, not static attributes, and evaluating them offline requires understanding intent rather than just checking a value.

As previously mentioned, Conditional Access is cumulative. Policies are not evaluated in a sequence where one policy overrides another. All applicable policies contribute to the final enforcement decision. Therefore, offline evaluation must preserve that behavior while still making it clear which policies are contributing definitively and which ones are contingent on missing signals.

The end result is that offline Conditional Access evaluation is not about producing a single yes-or-no answer. It is about understanding the decision surface: which policies clearly apply, which ones might apply depending on how certain signals resolve during sign-in, and which ones do not apply at all. That clarity is what makes offline analysis useful without pretending to know things that Entra ID only decides at runtime.

Introducing CAPSlock

With all of this in mind, I set out to build CAPSlock, an offline Conditional Access engine, with a specific goal in mind. I wanted a way to reason about Conditional Access behavior without having to touch the tenant, generate sign-ins logs, or rely on manual interpretation of policy output.

Rather than reinventing the wheel, CAPSlock is built directly on exported CAP data from ROADrecon. ROADrecon already does an excellent job collecting this information and duplicating that work would not add much value. Dirk-jan Mollema has already done a lot of the hard work by providing libraries that make interacting with the data ROADrecon gathers at a deeper level straightforward. Starting with ROADrecon made it possible to focus on policy evaluation logic instead of spending time parsing or normalizing raw exports.

At a high level, CAPSlock evaluates CAPs against a simulated sign-in context. Instead of relying on live authentication attempts, it takes a defined set of inputs such as user, resource, platform, and client characteristics, and reasons about how CAPs would behave given that context.

From the start, CAPSlock was designed around three core capabilities.

1. Policy Targeting and Scope Resolution

Before you can reason about enforcement, you need to know which policies are even in scope. Therefore, CAPSlock evaluates:

- User and group targeting

- Inclusion and exclusion logic

- Special constructs such as All or None

The goal here is simple: answer the question which CAPs could ever apply to a particular principal? This forms the foundation for everything that comes after.

Figure 4 – CAPSlock Policy Targeting

2. Offline What-If Engine

Once scope is understood, CAPSlock can simulate sign-in scenarios offline.

It evaluates policies using supplied inputs such as:

- User

- Resource

- Device Platform

- Client app

- Device context, where applicable

- And more

During evaluation, CAPSlock handles normalization and aliasing and classifies outcomes into:

– Applied (definitive), where all conditions are satisfied with the provided inputs

– Applied (signal-dependent), where applicability depends on signals not supplied offline

This distinction is intentional and avoids guessing Entra ID’s sign-in behavior.

Figure 5 – CAPSlock What If

3. Policy Analysis and Gap Detection

Building on top of the what-if engine, CAPSlock includes an analysis mode designed to help identify potential gaps in Conditional Access enforcement.

Rather than evaluating a single scenario, the analyzer permutates through sign-in conditions such as platform, client app, and location to explore how policies behave across different combinations. The goal is to surface scenarios where access may be possible without triggering a block or requiring multi-factor authentication (MFA).

This makes it possible to identify patterns such as:

• Enforcement gaps that only appear under specific sign-in conditions

• Policies that rely heavily on assumptions about platform, location, or risk

• Areas where Conditional Access coverage is incomplete or inconsistent

Demo Time!

So how can we use CAPSlock to identify gaps in CAPs? Let’s walk through a simple example.

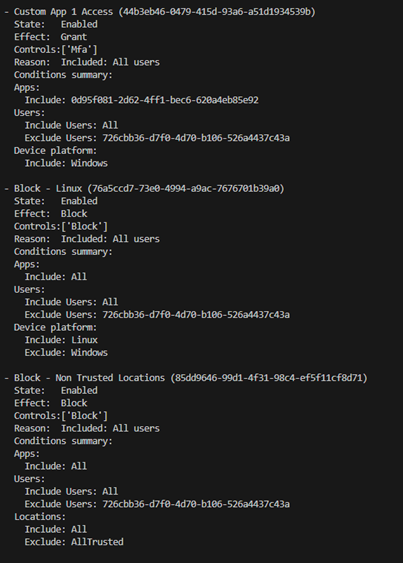

Let’s assume we have credentials for a low-level user, have already run ROADrecon to collect data from the target Entra ID tenant, and are now trying to access a resource named “Custom App 1” (id: 0d95f081-2d62-4ff1-bec6-620a4eb85e92) without hitting a block policy or being forced into MFA. CAPSlock lets us reason about how all of the CAPs in the tenant behave and where enforcement assumptions might break down.

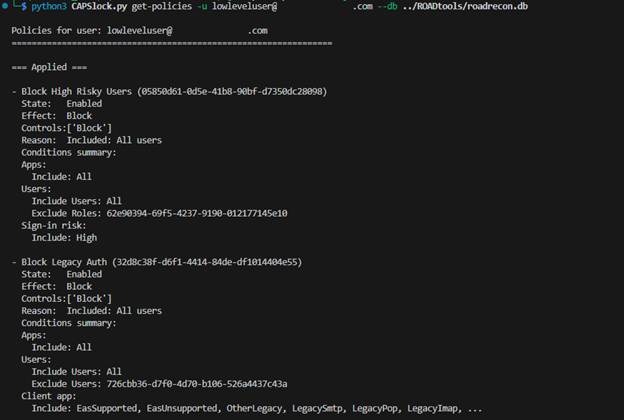

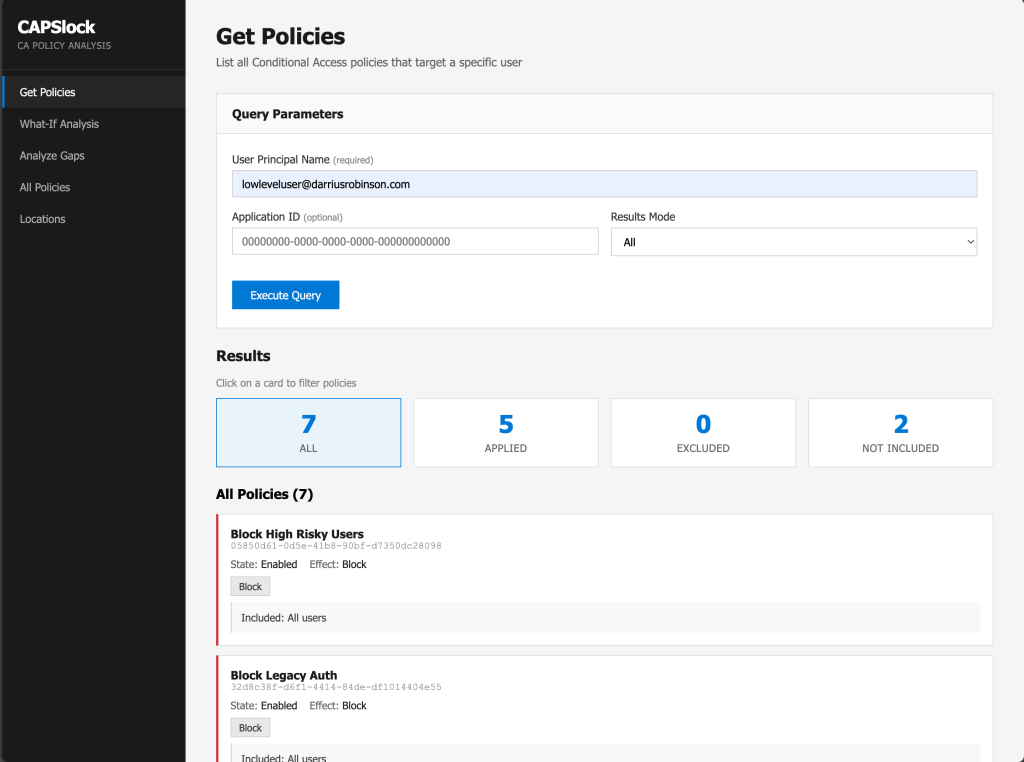

Step 1: Identify all policies that could ever apply

The first thing we should do is determine which CAPs could ever apply to our target user, and why.

Figure 6 – CAPSlock Obtaining Policies for Target User 1

Figure 7 – CAPSlock Obtaining Policies for Target User 2

This step is useful on its own, as it narrows the scope to only the policies that target the user directly or indirectly through explicit assignment, group membership, or roles.

In this example, we can already see something interesting. One of the policies indicates that all sign-ins from a Linux host would be blocked outright. This is useful to know early on as it tells us that certain device platforms are non-starter and not worth exploring further.

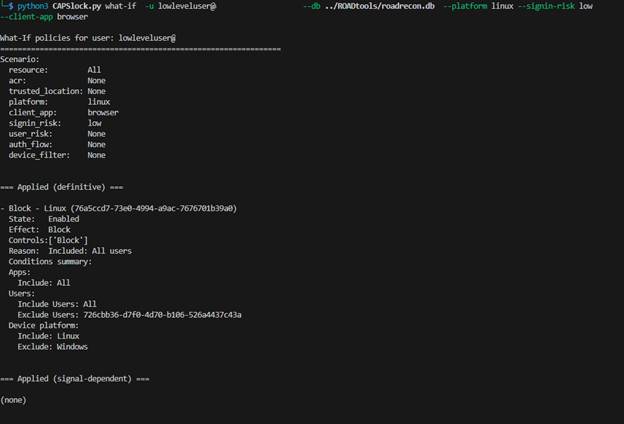

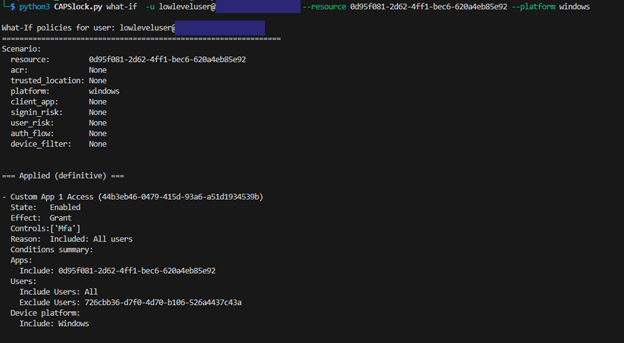

Step 2: Simulate sign-in scenarios

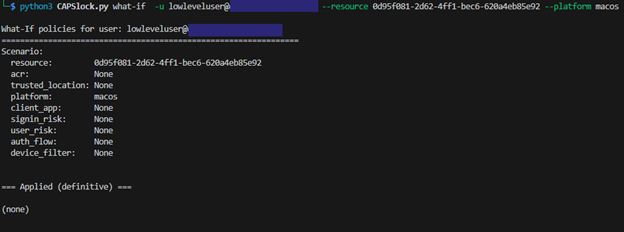

Next, we can simulate a sign-in attempt for the low level user accessing “Custom App 1” from a Windows host.

Figure 8 – Sign-in Scenario Windows 1

CAPSlock reports that one policy will definitively apply to this sign-in, and three additional policies could apply depending on other signals that we have not supplied.

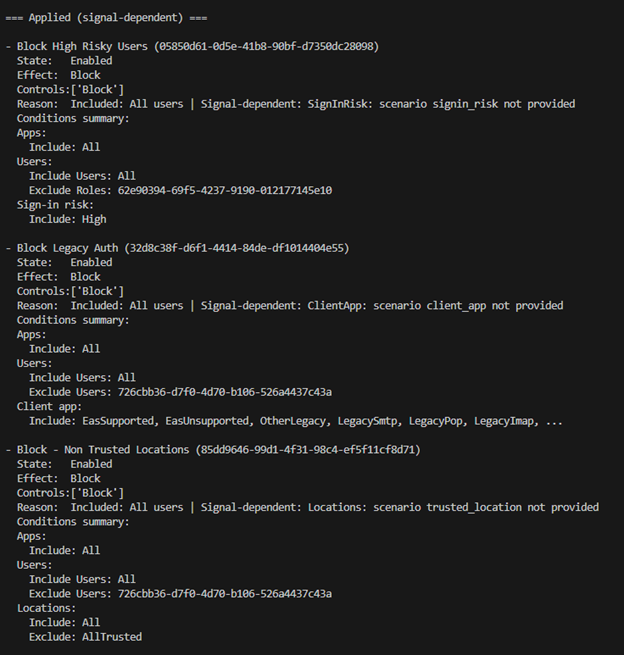

Figure 9 – Sign-in Scenario Windows 2

At this point, we know that regardless of any other signals collected during sign-in, MFA will be required. The additional policies tell us there are still conditions that could block access depending on how the sign-in resolves in practice. This is where we can start to make informed decisions about exploring alternative paths that might avoid enforcement.

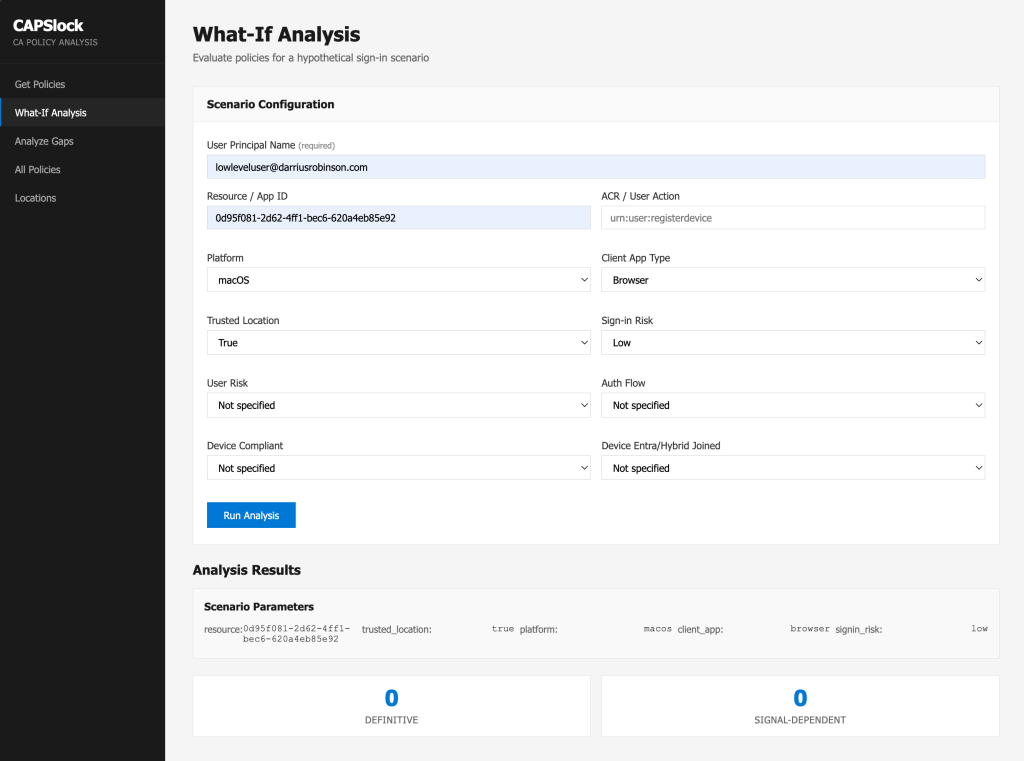

One alternative path is changing the device platform. We can run the same simulation again, but this time assume the sign-in is coming from macOS instead of Windows.

Figure 10 – No Definitive Policies Applies 1

This time, we notice that no policies definitively apply, but there are still three policies that could apply depending on signals obtained during an actual sign-in.

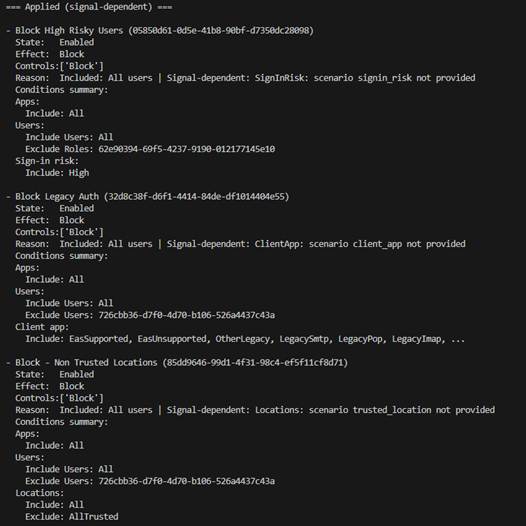

Figure 11 – No Definitive Policies Applies 2

At this point, we have identified a potential gap, but there are still additional considerations that could result in access being denied. If this were an actual assessment, this would be a reasonable point at which to attempt a login, but with a clear understanding of what could still go wrong.

Reviewing the remaining signal dependent policies shows that enforcement would occur if certain conditions were met, specifically:

- The user’s sign-in risk is high

- Legacy authentication is used

- The sign-in originates from an untrusted location

This clarity allows us to reason about the next steps needed to avoid triggering any CAPs.

This time, we simulate a sign-in from a macOS device using a browser, coming from a trusted location with a low sign-in risk. CAPSlock reveals that in this scenario, no policies apply.

Figure 12 – CAP Bypass Identified

At this point we can conclude that we have identified a gap. Under these conditions, access to “Custom App 1” is possible without being blocked or requiring MFA!

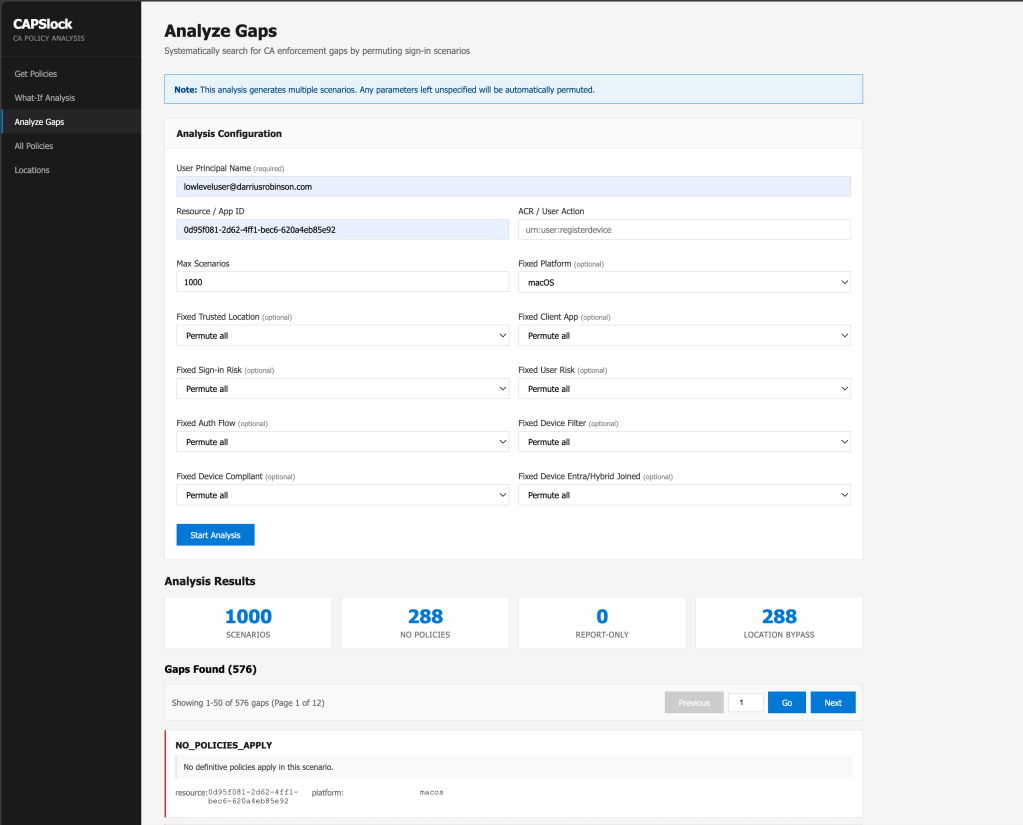

Alternate strategy: Automated analysis

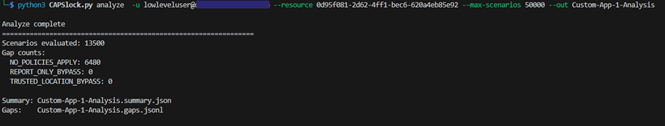

The previous strategy focused on manually evaluating specific sign-in scenarios to identify gaps. While this approach works well, and is the one I generally recommend, CAPSlock also includes the ability to perform automated analysis by permutating through sign-in scenarios.

Figure 13 – CAPSlock Analyze Summary

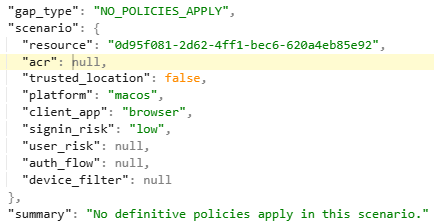

Figure 14 – Example of GAP Identified in JSONL File

The analyze function acts as a coverage analysis mode for Conditional Access. Instead of evaluating a single hypothetical sign-in like the what-if engine, it permutates through sign-in scenarios for a given user and target resource. Any sign-in attributes that are not explicitly provided, such as device platform, client app, trusted location, risk level, or authentication flow, are automatically varied up to a defined maximum. Each generated scenario is then evaluated using the same Conditional Access logic as the what-if engine.

This makes it possible to explore how policies behave across a wide range of realistic sign-in conditions, rather than testing one hypothesis at a time. For environments with large or complex policy sets, this approach can quickly surface cases that would be difficult or impractical to find manually.

For each scenario, CAPSlock identifies gaps where protections do not definitively apply. This includes cases where no policies are enforced at all, where only report-only policies apply, or where enforcement disappears under specific conditions such as trusted locations. The output consists of a high-level summary showing the number of identified gaps, along with a detailed, scenario-by-scenario breakdown that makes it clear exactly when and why enforcement drops away. Each gap is also written to a JSONL file, making it easy to review individual cases, post-process results, or feed them into other analysis workflows.

The results from analysis mode are best treated as a starting point. Identified scenarios can then be investigated further using the what-if feature to understand which policy assumptions are being relied on and whether those assumptions are valid in practice. While powerful, this approach can be verbose, which is why it works best when combined with targeted what-if analysis rather than used in isolation.

Web Interface

In addition to the CLI, CAPSlock also includes a web-based interface as an alternative way to interact with the engine.

Through the web interface, you can perform the same actions demonstrated earlier, including policy scoping, what-if evaluations, and analysis runs to identify gaps.

Practical Application

CAPSlock is built to reason about Conditional Access behavior, with a focus on understanding how policies interact holistically and when and why enforcement occurs.

For red teamers and penetration testers, this makes it possible to strategically analyze policies and identify gaps without generating sign-in. CAPSlock can assist in identifying which signals matter and where viable access paths may exist.

For blue teamers and administrators, the same analysis can be used to audit Conditional Access design. CAPSlock can help surface overlapping policies, unintended gaps, and controls that are only enforced under specific conditions, without impacting users.

In both cases, CAPSlock provides a way to reason about Conditional Access decisions offline and before taking action.

Constraints and Limitations

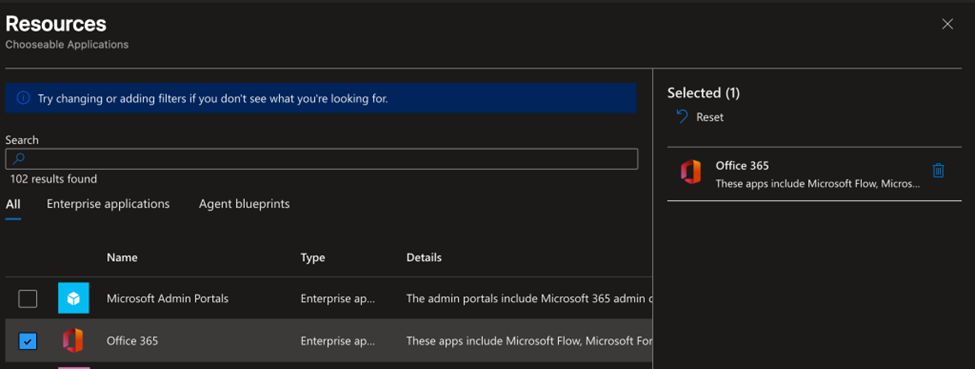

App Grouping

Within Entra ID, there are a large number of individual resources that CAPs can target. To make admins’ lives easier, Microsoft groups many of these resources into “app groupings”.

A common example is the Office365 “app grouping”[3], which represents a collection of resources spanning multiple Microsoft 365 services rather than a single application. More information on this can be found here.

Figure 15 – Office365 App Grouping

While Microsoft does publish what is included in the Office365 “app grouping” they are subject to change over time. Because of that, CAPSlock does not currently attempt to resolve individual resources into application groups during evaluation. Doing so would require constant maintenance to stay in sync with Microsoft’s definitions.

For now, it is recommended to supply the “app grouping” name or identifier directly when performing analysis, rather than individual resource IDs, although you can pass specific resource ids for more targeted policies.

AAD Graph Deprecation

Microsoft has been saying it for years. They are planning on deprecating Azure AD graph (AAD graph) and it looks like they have finally started making movement on this. As of the time of this writing, it is still possible to use AAD graph to dump policies as a standard user. This is expected to change once AAD graph fully deprecates.

Once this happens, policy collection will need to rely on Microsoft Graph. Unlike AAD Graph, accessing CAPs via Microsoft Graph requires explicit permissions that standard users do not typically possess. There is already a Microsoft Graph based branch of ROADrecon, and CAPSlock is designed to work with that data version as well. The primary impact is that future usage may require higher privileges to obtain the policy data in the first place.

Resources Permissions

At present, CAPSlock does not evaluate whether a user is authorized to access a targeted resource, it only highlights which, if any, policies would apply to a sign in scenario.

PIM and Group Membership Bypasses

Privileged Identity Management (PIM) allows users to temporarily activate eligible roles, which can change effective permissions or group membership and potentially alter Conditional Access targeting. Dynamic group memberships behave similarly by modifying group membership based on user attributes. Both represent identity state transitions that can change whether a policy applies or whether a user becomes excluded from enforcement.

CAPSlock evaluates Conditional Access based on the identity state captured during the ROADrecon collection. That means it is only as accurate as what was gathered at that point of collection. While a role eligibility table exists in the roadrecon.db, it was not populated during testing, and at present CAPSlock does not automatically model PIM activation or dynamic membership recalculation.

By default, CAPSlock does not simulate these state changes. However, a separate branch of the repository includes support for simulating alternate identity states using the –assume-role and –assume-group arguments. These flags allow you to evaluate how Conditional Access behavior would change if a user were assigned an additional role or group, without attempting to fully replicate PIM workflows or dynamic rule evaluation.

Conclusion

Conditional Access is one of the most important control planes in Entra ID, but it is also one of the easiest to misunderstand. As policies grow and overlap, enforcement behavior becomes harder to reason about, and assumptions about “what should happen” often drift from reality.

CAPSlock exists to close that gap. By evaluating CAPs offline and making enforcement behavior explicit, it provides a way to reason about policy scope, signal dependency, and potential gaps without touching the tenant.

Whether you are testing controls, validating policy design, or auditing enforcement coverage, the underlying problem is the same: understanding how Conditional Access behaves under different conditions. CAPSlock is designed to support that understanding and to make Conditional Access analysis more intentional, repeatable, and defensible.

The CAPSlock project is available on GitHub at https://github.com/rbnroot/CAPSlock. Feedback, issues, and contributions are welcome.